US Inflation at 40-Year High

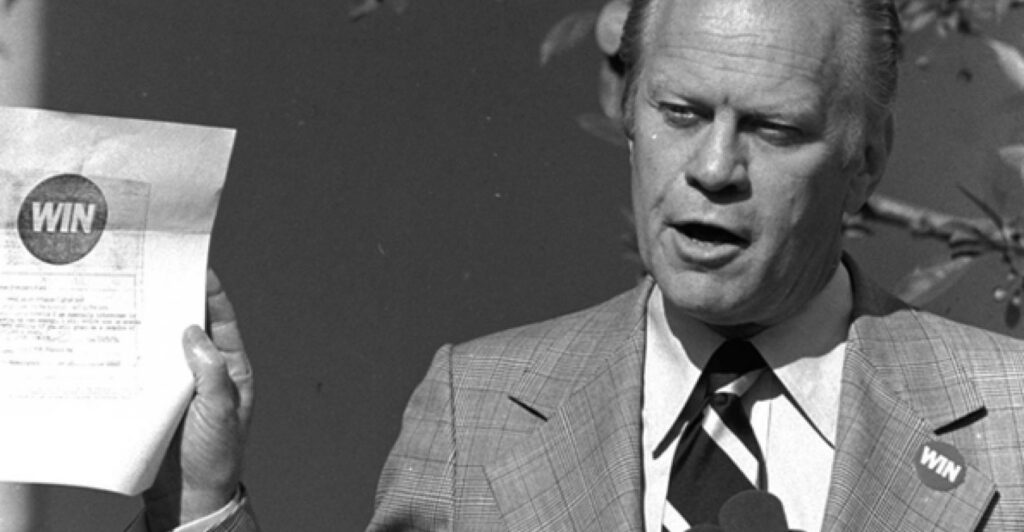

Can the Misery Index be far behind?

Those of us who are old enough to remember inflation being a central issue in American politics are, well, pretty old. It has been pretty much a non-factor for the last several presidential administrations, kept under control through aggressive anti-inflation policies managed by the Federal Reserve. The combination of a massive set of shocks set off by the COVID pandemic and unprecedented federal spending in response has changed that.

WSJ (“U.S. Inflation Accelerates to 7.5%, a 40-Year High“):

U.S. inflation accelerated to a 7.5% annual rate in January, reaching a four-decade high as strong consumer demand and pandemic-related supply constraints kept pushing up prices.

The Labor Department on Thursday said the consumer-price index—which measures what consumers pay for goods and services—was last month at its highest level since February 1982, when compared with January a year ago, and higher than December’s 7% annual rate. Inflation has been above 5% for the past eight months as a U.S. rebound from earlier in the Covid-19 pandemic created imbalances in the economy.

The so-called core price index, which excludes the often-volatile categories of food and energy, climbed 6% in January from a year earlier. That was a sharper rise than December’s 5.5% increase, and the highest rate in nearly 40 years.

On a monthly basis, the CPI increased a seasonally adjusted 0.6% last month, holding steady at the same pace as in December.

rices were up sharply for a number of everyday household items, including food, vehicles, shelter and electricity. A sharp uptick in housing rental prices—one of the biggest monthly costs for households—contributed to last month’s increase.

Used-car prices continued to drive overall inflation, rising 40.5% in January from a year ago. However, prices for used cars moderated on a month-to-month basis, increasing by 1.5%. That was down from a 3.3% increase in December and the smallest gain since September—a possible sign that a major source of inflationary pressure over the past year could be easing.

Food prices surged 7%, the sharpest rise since 1981. Restaurant prices rose by the most since the early 1980s, pushed up by an 8% jump in fast-food prices from a year earlier. Grocery prices increased 7.4%, as meat and egg prices continued to climb at double-digit rates.

Energy prices rose 27%, easing from November’s peak of 33.3%. But the jump in electricity costs was particularly sharp when compared with historical trends, with prices up 10.7% from a year ago and 4.2% from December. The latter was the sharpest one-month rise since 2006.

WaPo (“Prices climbed 7.5% in January compared with last year, continuing inflation’s fastest pace in 40 years“):

Prices continued their upward march in January, rising by 7.5 percent compared with the same period a year ago, the fastest pace in 40 years.

Inflation was expected to climb relative to last January, when the economy reeled from a winter coronavirus surge with no widespread vaccines.Today’s new high inflation rate reflects all the accumulated price gains, in gasoline and other categories, built up in a tumultuous 2021.

In the shorter term, data released Thursday by the Bureau of Labor Statistics also showed prices rose 0.6 percent in January compared with December, same as the November-to-December inflation rate, which officials revised upward slightly.

As with previous months, higher prices reached into just about every sector of the economy, leaving households to feel the strain at the deli counter, shopping mall and just about everywhere else.

“I’m worried,” said Diane Swonk, chief economist at Grant Thornton. She expects inflation to begin falling in the next few months but warns that it might be difficult to bring price growth down to pre-pandemic levels.

“The Fed is counting on inflation abating somewhat on its own,” Swonk said. “The problem is that even as inflation abates, it may not cool enough not to burn. Some of the inflation we are seeing is becoming more entrenched in the service sector. There is no playbook for derailing inflation in this environment.”

Tuesday’s episode of The Ezra Klein Show, “What the Heck Is Going on With the U.S. Economy?” was helpful in putting all of this into context. The guest was Jason Furman, a Harvard economics professor who was chair of Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers from 2013 to 2017. He was neither alarmist nor dismissive of the situation.

I think there are two sets of misses. And I’m not sure of the exact ratio of the two. The first set of misses was that— by the way, we’re not out of this. We’re really deep into it right now. But in terms of people’s economic behavior, we are mostly out of it. People are mostly spending as normal. They’re living a normal-ish life, or at least they were a month ago. And I think they probably will a month from now.

So when I say out of it, I’m not talking about out of the human tragedy. I’m talking about out of it in the very narrow sense of the economy. So I think one miss was that this had more in common with a natural disaster. That when the virus came, it would derail activity. When the virus either left, or some of the dangers of the virus, or people got used to it, that that would come back.

The second part of it is the policy response was gargantuan. $5 trillion I did not imagine being spent. And basically policymakers said, yes, there’ll be a recession in the economy, but we’re going to give you so much money that for most people you’re actually going to get more money than you would have made if you had stayed in your job. And so they, in some sense, immunized people from the recession. And it’s probably the combination of these two — the natural disaster-like features plus the enormous policy response — that got us where we are today.

Which makes sense. While I was dubious of some of the ways we threw money at the problem in the early going, I was generally in favor of it. While means-testing to make sure that the money only went to those who needed it would have been my gut preference, it was obvious that speed was of the essence and that it was better to over-spend than under-spend. But it’s not at all clear that the massive “Rescue Act” that President Biden passed made sense by that point in the pandemic. Furman is conflicted:

I think there’s two different questions. One is would I have voted for the American Rescue Plan in an up-or-down vote? Absolutely yes. A lot of what we’ve seen — the amazing things we’ve seen in terms of, for example, poverty overall and child poverty — and we haven’t gotten the data for 2021. I think that’ll be even better than it was in 2020, and that itself was down— is thanks to the American Rescue Plan.

There’s then another question, though, which is if I could have redesigned it and cut it in half, could I have gotten 95 percent of those benefits and a decent amount less of the cost? I think the answer to that question is probably yes, too. And so then the question is every bit of legislation is imperfect. Everyone always has the way they could have improved it. How harshly should one judge in that circumstance?

Regardless, inflation is a huge problem, both politically and economically. From the perspective of Biden and the Democrats, it makes already-dim prospects of retaining power in the midterms much harder. More importantly, it means that most of us have less buying power than we had before. If one’s wages went up 2.5% and inflation is 7.5%, then it’s effectively a 5% pay cut. Further, the amount of savings many people accumulated during the pandemic because they couldn’t travel, go to dinner, and the like all took a 7.5% loss. (Of course, those who are in debt also got a 7.5% haircut, which is an important offset but less obvious on a day-to-day basis.)

As to whether this is all an anomaly or something that will continue for some time, Furman is decidedly two-handed.

So here’s where the two hypotheses will differ and how we can distinguish between them. And the question is, what happens to prices in the non-freakish areas over the next year? So one mental exercise is what would inflation be if used car prices hadn’t gone up so much and everything else was exactly the same? That’s the micro-perspective.

The macro-perspective says what if used car prices didn’t go up so much, maybe people would have had more money to spend on something else and some other price would have gone up. Or to make a prediction over the next year, it would say that service price inflation is going to be faster over the next year than it was over the last year. So yes, the freakish stuff on the goods side will end, but now people will have more money to spend on services. We’ll see more inflation there.

And one of the issues is services are so much bigger than goods. So it only takes a one percentage point increase in the inflation rate for services to undo a five percentage point reduction in goods. So that to me is the big difference. Do you think of your story as in everything else being equal, which is the micro-story, or as, yes, you deflate the balloon here, but it pops up there. That’s the macro-story. And the way to distinguish will be to look at service prices over the next year.

His best guess:

Yeah, there’s different ways to measure inflation. So I am roughly in the 3 to 4 percent range, but that is not a super scientific forecast. So as you said, 1 to 6 percent wouldn’t shock me. 3 percent would be more for the thing the Fed is targeting — the personal consumption expenditure price index — 4 percent would be more for the CPI, which tends to get most of the press attention.

There’s a lot more in the conversation, only some of which is about inflation. And, frankly, even the sharpest minds are just guessing at this point.

We’re still on hold for the PPI numbers next Tuesday, but they’re well expected to underline what these already say – the Fed is going to have to (aggressively) intervene.

He left out part of this:

People are mostly [debt] spending as normal. They’re living a normal-ish life, or at least they were a month ago [made possible only by spending money they have not yet earned & piling up debt in the process].

Which is why total US household debt has increased by some $1.4 trillion since the end of 2019, to its highest levels since 2007. There is a point where all of this implodes IMO.

Oil currently $91/bbl.

Nat gas $4/MMBtu

Other energy strong also.

Pretty much all goods and services have energy as a cost of doing business, so this drives a lot.

If we can keep things so that only the bottom 50 or 60% of the population is impacted by inflation beyond the level of annoyance, the misery index will stay a slogan of the past. It was a problem in Reagan’s day because middle class Americans were being priced out of owning homes and scummy union employees (such as myself) were staying afloat thanks to generous COLAs written into our contracts early on. Neither of those issues are current anymore. Most actually middle-class Americans have been priced out of the housing market for 20 or 30 years, and unions keeping workers afloat are a fond remembrance of a bygone era. We’re good for now!

@HarvardLaw92: ” There is a point where all of this implodes IMO.”

While I agree in principle, check back with me when consumer credit bankos have started endangering banks.

Chipotle had to raise prices 10% because of inflation. Oh yeah…they paid their CEO a 137% raise and revenue was up 22%.

BP records highest profits in 8 years.

Meat packers profit margins jumped 300% during the pandemic.

Apparently price gouging and inflation are actually synonyms?

Inflation is created by the money supply growing faster than economic productivity. If the money supply needs to be reduced, the easiest way to do it is by increasing taxes.

Like repealing trillions in taxcuts that didn’t help middle or low income earners to begin with.

It’s definitely worth looking at the inflation rates of other countries as well — according to some quick googling UK is at 5.4%, Germany at 5.3%, Canada 4.8% (December or January, year over year, mentioned in articles like “Germany has highest inflation rate since 1993”)

That global rise in prices (among similar countries) suggests that a large chunk of this really is supply chain disruptions, and that the Fed acting aggressively, as @HarvardLaw92 seems to be asking for, isn’t going to be effective, unless they turn out to be part time longshoremen or something.

It’s a weird economy right now — bankruptcies are way down, unemployment is down, workers are unionizing, wages are going up, people are able to switch jobs, but there’s also price increases in food, goods and housing. Spending is returning to normal in levels, but still focused more on things rather than services — more home exercise equipment, less gym memberships.

The Fed intervening is likely to affect good parts of the economy more than the bad. I think we need to ride this out, or we just hurt a lot of people for basically nothing.

(And, unemployed people are also going to vote against the party in power, using the Fed to try to stop inflation won’t even help at the polls)

Pandemic waves are going to disrupt shipping and manufacturing, and that’s a vulnerability of the Just In Time delivery. Building slack into the economy to weather disruptions is going to be hard and take time, and may not even happen, but it’s not something the Fed can do by raising interest rates.

And then there is housing, which is an entirely separate problem contributing to the inflation rate — rents are up in many metro areas by 25% year over year.

@Daryl and his brother Darryl:

Profit taking, not price gouging, you filthy communist!

Ok, seriously though, there were some businesses where the prices were being held in check for a while, despite rising costs, and which are now making up for it. Many areas had a temporary restriction on rent increases, plus there was the no-eviction mandates for the pandemic, which have messed up the rental market for a bit, for instance.

I would be very wary of all measurements over time periods that start during the pandemic. That includes the top line 7.2% YoY inflation rate, as 2021 was not a particularly normal year.

The political pain is going to be based on short term inflation rates, but the actions needed (or not) should be based on longer term rates, and addressing the peculiar vulnerabilities that the pandemic has exposed as much as traditional causes.

Both a heart attack and a gunshot wound can cause chest pain. There is no one-size-fits-all solution for chest pain. Same with inflation.

@Gustopher:

We are sitting dead in the middle of three concurrent asset bubbles – equities, commodities, and housing. Four if you count the out of whack bond yields. Those did not get inflated by supply chain disruptions. They largely got inflated by cheap capital. Supply chain disruptions play a part, but you can not inject mountains of additional capital into an economy, any economy, spike wages, and not expect to get inflation. Leave it alone and you will get structural inflation.

Fed rate increases will play a part, but the largest effect is going to be felt from the Fed turning off the cheap capital tap in March and reversing the flow when it begins to clear that enormous (and unsustainable) mountain of assets it has accumulated on its balance sheet.

My dumb take is that the bubbles connect to the just-in-time balance-sheet hyping and every game that finance has been playing with normal things and that all connects to inflation, and it’s not the 70s. Inflation in the 70s came as the post-war boom ended. It’s a totally different economy.

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

I was speaking more to: it begins to implode when the capital markets begin to contract and the credit markets pull back from lending as a result (which is precisely the track the Fed has charted). People forget that the vast, vast majority of credit card debt is variable. Rates go up, while credit lines begin to shrink. We’ve seen the movie before.

@Modulo Myself:

Inflation in the 70’s came about when we exited Bretton Woods (gutting the value of the dollar in the process) and cranked up the printing presses to pay for Vietnam and full employment policy goals. You can not flood an economy with cheap capital and not get inflation.

@Gustopher:

Multiple factors, supply chain issues, labor shortages, difficulty finding workers, commodity prices, etc.

As for money supply, sure, that’s textbook economic theory if you buy that thinking, but I think in the real world cause and effect are switched.

@Daryl and his brother Darryl: No but apparently populist innumeracy and economic illiteracy knitted together to make Just So Stories for having a set of bad guys as excuses are universal.

@HarvardLaw92: Well, you can not flood an economy with cheap money / liquidity and not get inflation unless there a significant deflation factors or monetary destruction going on.

As it happens this was the case pre-pandemic since roughly the financial crisis of 2008. The countervailing factors overwhelmed inflationary effects (thus all the inflation poopooing seen from the US Lefties these past 9 months in response to what one must admit is Boy Who Cried Wolf inflation warnings from the righty inflation hawks; of course said Lefties ignored that non Wolf Crying Boys were warning there was some real smoke this time)

But that is now changed, and oops, time to dust off old 1970s playbooks. Early as of yet, not 1977 certainly but if not address, can get there.

@Gustopher: Every single relevant Central Bank has been engaged in extremely loose monetary policy so the examples hardly say that supply chain disruption is the driver at this time – versus overly accelerated demand that has jumped ahead of capacity and productivity. Everyone essentially had the same easing policies, and have had for a good decade.

It is not credible now to blame ‘supply chain disruption’ with the implicit argument that it is all transitory and going away once kinks are worked out.

But of course your argument, well it is a nice 21st century update of the rather similar, even nearly identical ones of the 1970s.

Having lived through inflation rates of over 100% in the late 80s and early 90s, the current moment is bad but not that bad.

No misery index unless the unemployment rate substantially increases.

Also different from the 70s: even if the Fed raises rates (which they will) the cost of borrowing is still going to be radically lower than it was 40 years ago.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Assuming we see the desired reduction in CPI/PPI, agreed. We won’t hit 70’s interest rates, but for an economy accustomed to essentially zero rate capital, it’s going to be unpleasant nonetheless. 100bp in hikes (which is what the market is expecting / pricing in) isn’t going to get it done IMO.

UK interest rates currently at 0.5%; US at 0.25%.

So you can expect at least a doubling of effective rates, probably more; considerably more.

To veterans of the last millennium, 0.5 or 1 or even 2% may seem minimal.

But it is going to cause holy hell in the markets as “free money” positions get unwound.

Taxation as an alternative always sound great, until you get down to the dirty politics of it.

And the fact that in an economy where the majority of spending power lies with the majority of the population, that’s who you must end up hurting to ameliorate effective money pressures.

The rich tend not to spend so much, simple as that.

And to be highly adept at shifting assets into non-taxed areas.

There are good reasons why out of control inflation rarely got halted by political decisions to tax away the surplus money.

@JohnSF:

Pointing out the taxation angle is mostly about pointing out how much of the inflation talk is bad faith concern-trolling: they’re only concerned about inflation if the solution is abusing the poor. If fixing inflation requires THEM to give up something, then suddenly it’s not THAT big of a problem.

@HarvardLaw92: Yeah. That wasn’t the part of the scenario I was looking at. Good point.

So when does the inflation get reflected in bank interest rates for my savings account?

Companies are always looking for an excuse to charge customers more while not passing on savings, so I’m dubious.

@grumpy realist:

After as long a lag as your bank can get away with, of course.

🙂

@Stormy Dragon:

It’s more a case of taxation, in and of itself, is mostly a vehicle for increasing monetary velocity. Tax hikes, by themselves, are just a vector for increasing the amount and periodicity of the money that’s circulating and because of that actually exacerbate inflation. You can’t constrain an economy (which is how you reduce inflation) without constraining spending. Unfortunately, simply by virtue of segment size, the middle and lower classes constitute the bulk of consumer spending and that’s where the constraints have to effect themselves to control inflation.

@Stormy Dragon:

Also, being an oldish sort, I can recall the 1970’s when UK higher rate income tax (can’t recall threshold though) was 83%.

Didn’t stop inflation peaking at around 25% in the mid Seventies.

IIRC there was also a capital gains tax levy of 30% at that time.

So, taxes as a brake on inflation?

Perhaps, perhaps not also.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Yep. My wife and my first mortgage was 14.5%. We had friends who didn’t have as much employment time that paid 17%. A quick check says the average rate yesterday for a 15-year fixed rate mortgage was 3.3%.

@JohnSF:

The maximum bracket for US income taxes in 1970 was 70%, which is precisely where it stayed until 1982, when it dropped to 50%. Didn’t have the slightest bit of an effect on inflation throughout that period. IMO about the only way that you can tax hike yourself out of inflation is by accompanying those hikes with monetary destruction (which this government is not going to do)

@HarvardLaw92:

Exactly.

Best to taper off gently with interest rates, and let air out of bubbles relatively slowly, and exercise a bit of retraint re. debt creation.

Prune it back fairly gently.

Alternative can be the genuine money detonation we saw under Conservatives in UK 190’s, with unemployment spiking to 12%, and over 10% for much of that decade.

Though no matter how gradual the deflation, I suspect the end of “free money” for some business models is going to cause a lot of red faces on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley. And the City, of course.

“It’s only when the tide goes out you discover who’s been swimming naked.”

@JohnSF:

Agreed. I’m hoping that the hikes (I think 200bp will eventually be required, but I doubt we’ll see that much this year) combined with de facto destruction as Fed sucks capital out of the economy through clearing its balance sheet does the trick. The path ahead, in theory, is as clear as a bell. Implementing it, however, is a razor thin tightrope which I’m glad I’m not charged with walking.

And I agree, as well. I’ve been hoping that – since the market has had ample warning of what is coming – that we’d see the gradual beginning of bubble deflation, but as usual, it’s just full speed ahead because only other people hit the iceberg. All bubbles deflate – the question isn’t when but instead how quickly. There are some asset classes which are indeed not going to be having the happiest of days a few months from now.

@Michael Cain:

The trick there is where was it before? The average rate on a 30 year fixed has increased by 48bp in the span of 4 weeks (from 3.27 to 3.75, which is a 22 month high), or 12bp per week, and Fed hasn’t even started actually raising rates yet. We won’t see 1970’s rates, absolutely, but I’m willing to bet we’ll see rates well over 5% to touching 6% before this adventure is over with.

Couple that with the gargantuan increase in mortgage debt that has taken place over the last year or two (primarily refis), and you’ve set the table for a housing bubble that’s going to deflate. A whole lot of people are going to find themselves underwater. They’ll still have their nice low legacy rate, but it won’t matter much if they’re trying to sell.

This may be a dumb question: do other countries calculate inflation the same way we do, and are their rates exactly comparable or somewhat comparable, or comparable if we do a thing to our numbers or their numbers?

And how much of a role did the the oil shocks/oil embargo against the US in the 70s have in inflation at the time? (I’m really asking, I don’t know)

@Steven L. Taylor:

This. The fact of the matter is that in recent recessions the Fed has had their hands tied because they couldn’t lower interest rates that were already at zero. Having interest rates move up a bit will be good for the long run.

@Mike in Arlington:

Generally speaking, yes. They all establish a basket of representative product classes / services, the prices of which are tracked over time to establish the rate of increase / decrease. In the US, we call it the CPI (consumer price index). Different countries can and will establish different basket constituents (for example, US CPI does not include the price of housing, while some others may), but the premise underlying calculation of the delta is pretty much the same.

TLDR: the calculation methodology is pretty consistent, but the basket of goods and services treated as representative of the economy as a whole are subject to variability.

@Mike in Arlington:

Add to the above (no edit button…) :

Basket of goods and services [and the weighting applied to each constituent of the basket] … are subject to variability.

@Stormy Dragon: They keep ignoring the elephant in the room with red-herring discussions about rate hikes. The #1 tool the USG has to sop up excess money supply–IS RAISING TAXES

@Jim Brown 32:

As long as they don’t redistribute it (which they do, in spades)

@HarvardLaw92:

This will vary from region to region. Here in New England, new home construction never really kicked into high gear after the 2008 recession–we still have very limited availability. With so little supply, most of the regional assessments I’ve seen indicate that home prices here will remain pretty high, even if interest rates go up. They might not be at the sky-high levels they are now (which are insane), but that’s not necessarily a bad thing either.

@Jen:

Absolutely. I was speaking in a broad market context, but you’re correct – local / regional markets which experienced less of a bubble effect would also be less impacted by the bubble deflating

Ah, the good old days. My SBA loan, under that fool Jimmy Carter, was 2 points floating over prime and soon I was paying 21% interest and not making any profit. It took Reagan’s election to bring it down. Now we have that fool Biden, and I have that deja vu feeling. Guess we need another Republican President to handle things correctly.

@John430: Oh yeah, Reagan tripled the national debt during his eight years in office. And it was Carter, not Reagan, who appointed Volcker, whose interest rate increases (albeit with dire economic effects) killed the inflationary dragon. But all must bow down to the shrine of St. Ronald of Hollywood.

@Daryl and his brother Darryl:

Thank you, Darryl, I think also the CEO of Starbucks and perhaps of Tyson Foods are posting record breaking stock buybacks and CEO raises? *koff koff* But sure it’s all Biden’s fault. Or OPEC’s. $15 an hour minimum wage is looking kind of quaint now.

We are having exactly the kinds of problems that we tried to have a year ago. Yes, giant gooses from the Fed and big surges in spending by the government will cause inflation. It will also improve growth (in real terms!) and employment (it looked like it didn’t, but now we see that it did, by a lot!).

We are dealing with a pretty difficult environment, and it’s hard for me to see how any government could possibly do better. Of course, if you have the point of view of some rich guy who doesn’t have to care at all about having a job and but stands to lose some potential upside due to inflation eating away their booked lending, yeah, you think this is terrible.

Higher prices at the gas pump hurt everyone, but gasoline purchases don’t normally make that big a fraction of someone’s budget.

Lost in all the weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth is the fact that most Americans have enjoyed government handouts over the course of the pandemic which far exceed a modest loss of inflation-caused income or savings. Anyone who claims to be “struggling” financially because of a few months of c. 7% inflation is a very poor money manager.

America had the choice of risking an extended recession or risking a bout of moderate inflation. It made the correct choice. Without the government stimulus, the media (and Trump Republicans) would currently be complaining about another snail-paced recovery with its associated high unemployment. Last year we heard again and again that “Too much stimulus is better than not enough!” But pundits have the memories of goldfish, and after all, it’s long been known that this is Jimmy Carter’s second term.