14th Amendment Solutions

One weird trick could save us from Trump.

The legal scholars J. Michael Luttig and Laurence H. Tribe take to The Atlantic to argue “The Constitution Prohibits Trump From Ever Being President Again.” It’s an argument that I’ve seen made multiple times since the Capitol Riot but seems to be gaining steam.

As students of the United States Constitution for many decades—one of us as a U.S. Court of Appeals judge, the other as a professor of constitutional law, and both as constitutional advocates, scholars, and practitioners—we long ago came to the conclusion that the Fourteenth Amendment, the amendment ratified in 1868 that represents our nation’s second founding and a new birth of freedom, contains within it a protection against the dissolution of the republic by a treasonous president.

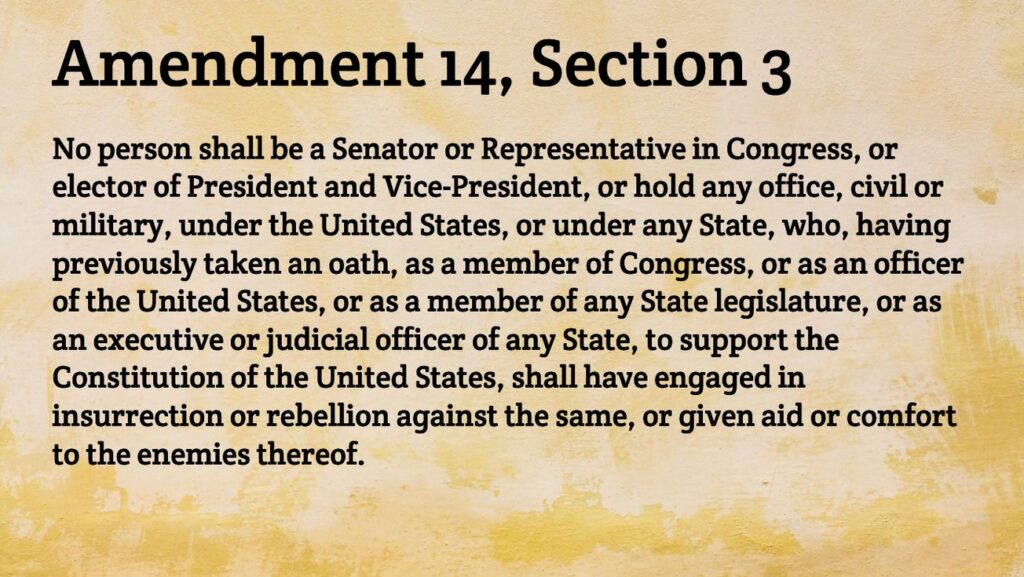

This protection, embodied in the amendment’s often-overlooked Section 3, automatically excludes from future office and position of power in the United States government—and also from any equivalent office and position of power in the sovereign states and their subdivisions—any person who has taken an oath to support and defend our Constitution and thereafter rebels against that sacred charter, either through overt insurrection or by giving aid or comfort to the Constitution’s enemies.

The historically unprecedented federal and state indictments of former President Donald Trump have prompted many to ask whether his conviction pursuant to any or all of these indictments would be either necessary or sufficient to deny him the office of the presidency in 2024.

Having thought long and deeply about the text, history, and purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment’s disqualification clause for much of our professional careers, both of us concluded some years ago that, in fact, a conviction would be beside the point. The disqualification clause operates independently of any such criminal proceedings and, indeed, also independently of impeachment proceedings and of congressional legislation. The clause was designed to operate directly and immediately upon those who betray their oaths to the Constitution, whether by taking up arms to overturn our government or by waging war on our government by attempting to overturn a presidential election through a bloodless coup.

The former president’s efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election, and the resulting attack on the U.S. Capitol, place him squarely within the ambit of the disqualification clause, and he is therefore ineligible to serve as president ever again. The most pressing constitutional question facing our country at this moment, then, is whether we will abide by this clear command of the Fourteenth Amendment’s disqualification clause.

We were immensely gratified to see that a richly researched article soon to be published in an academic journal has recently come to the same conclusion that we had and is attracting well-deserved attention outside a small circle of scholars—including Jeffrey Sonnenfeld and Anjani Jain of the Yale School of Management, whose encouragement inspired us to write this piece. The evidence laid out by the legal scholars William Baude and Michael Stokes Paulsen in “The Sweep and Force of Section Three,” available as a preprint, is momentous. Sooner or later, it will influence, if not determine, the course of American constitutional history—and American history itself.

I’ve followed Baude since he was an undergrad at Chicago blogging at a now-defunct Crescat Sententia. Indeed, he’d agreed to blog here but never got around to it, presumably getting too caught up in the rigors of Yale Law. He wound up clerking for Chief Justice Roberts and is now a professor at Chicago Law. (Just think how far he could of gone with OTB on his CV!)

I re-skeeted the notice of the above-linked article’s publication at Bluesky the other day but never got around to reading it beyond the abstract, the key bit of which is this:

First, Section Three remains an enforceable part of the Constitution, not limited to the Civil War, and not effectively repealed by nineteenth century amnesty legislation. Second, Section Three is self-executing, operating as an immediate disqualification from office, without the need for additional action by Congress. It can and should be enforced by every official, state or federal, who judges qualifications. Third, to the extent of any conflict with prior constitutional rules, Section Three repeals, supersedes, or simply satisfies them. This includes the rules against bills of attainder or ex post facto laws, the Due Process Clause, and even the free speech principles of the First Amendment. Fourth, Section Three covers a broad range of conduct against the authority of the constitutional order, including many instances of indirect participation or support as “aid or comfort.” It covers a broad range of former offices, including the Presidency. And in particular, it disqualifies former President Donald Trump, and potentially many others, because of their participation in the attempted over-throw of the 2020 presidential election.

The article is 126 pages long. The contention that I was most skeptical of is the second: that it’s self-executing. But that’s because they mean it in a theoretical, not practical sense. The long section defending that argument begins,

Though too many constitutional law teachers and casebooks begin their study of the Constitution with questions of judicial review, and cases like Marbury, in doing so they put the cart before the horse. The horse is the Constitution, which is itself the “supreme law of the land.” Our system is one of constitutional supremacy, not judicial supremacy or legislative supremacy. As a general matter, this means that it is the Constitution which states the law, and it is the job of government officials to apply it, not the other way around.

This general truth is no less true of Section Three. Section Three’s language is language of automatic legal effect: “No person shall be” directly enacts the officeholding bar it describes where its rule is satisfied. It lays down a rule by saying what shall be. It does not grant a power to Congress (or any other body) to enact or effectuate a rule of disqualification. It enacts the rule itself. Section Three directly adopts a constitutional rule of disqualification from office.

That’s true, of course, at least when the meaning of the words is clear. Amusingly, they give as an example the one that immediately came to my mind: Article II’s provision that only those 35 or older are eligible to be President. But I would contend that, despite the similarity of language with that provision, Section 3 can’t be self-executing because, unlike someone’s age, which can be established using a birth certificate and a calendar, “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” are questions of interpretation. And, while I’m amenable to their argument that the section was not merely limited to the Civil War, I strongly believe that judicial determination that someone had participated in an insurrection or rebellion would be required to apply it in any other case.

Baude and Paulsen disagree. Their argument for this, stretching over several pages, is too long to excerpt here. Briefly, though, they contrast it with the Constitution’s provisions on Treason and impeachment, which specify how those actions are carried out, contending “Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment, by contrast, is offense, conviction, and punishment all rolled in to one.”

This seems absurd to me but they counter,

More difficult it may be, to interpret and apply the disqualification of Section Three than the dis-qualifications of age, citizenship, and residency. But the fact of difficulty is a non sequitur. The fact that it might be hard for us to know today what a legal rule means (or how it applies) does not mean that it is not the legal rule. The Constitution says what it says and we must try to apply it as best we can. To start by asking what is easy for us, and then to assume that the Constitution must mean something that makes our lives easy, is as fallacious as drawing the curve before gathering the data points.

Which, frankly, makes my head hurt! As does the next paragraph:

Resistance might also come from the problem of enforcement. The Constitution is generally self-executing law, but still, somebody has to enforce it. Somebody has to read it, understand it, and ensure that our practices conform to its commands. (Many somebodies, actually, as we discuss shortly.) This is true, but again it is a non-sequi-tur. It is true that government officials must enforce the Constitution, and who does this and how they do it are important questions, maybe the central questions of con-stitutional law. But the meaning of the Constitution comes first. Officials must en-force the Constitution because it is law; it is wrong to think that it only becomes law if they decide to enforce it. Section Three has legal force already.

If somebody has to decide what the law is, then by definition it’s not self-executing. For Trump to be disqualified, somebody has to adjudge that 1) an insurrection or rebellion occurred and that 2) he engaged in it and/or gave comfort to those who did. And they seem to agree:

Who has the power and duty to do this? We think the answer is: anybody who possesses legal authority (under relevant state or federal law) to decide whether somebody is eligible for office. This might mean different political or judicial actors, depending on the office involved, and depending on the relevant state or federal law. But in principle: Section Three’s disqualification rule may and must be followed—applied, honored, obeyed, enforced, carried out—by anyone whose job it is to figure out whether someone is legally qualified to office, just as with any of the Constitution’s other qualifications.

These actors might include (for example): state election officials; other state executive or administrative officials; state legislatures and governors; the two houses of Congress; the President and subordinate executive branch officers; state and fed-eral judges deciding cases where such legal rules apply; even electors for the offices of president and vice president. We will discuss in detail some of these examples pres-ently. But two points are important to keep clear at the outset: First, all of these bodies or entities may possess, within their sphere, the power and duty to apply Sec-tion Three as governing law. Second, their authority to do so exists as a function of the powers they otherwise possess. No action is necessary to “activate” Section Three as a prerequisite to its application as law by bodies or persons whose responsibilities call for its application. The Constitution’s qualification and disqualification rules exist and possess legal force in their own right, which is what makes them applicable and enforceable by a variety of officials in a variety of contexts.

I’m exceedingly skeptical that state election officials have the authority to simply declare that a candidate for office is guilty of a crime and thus disqualified from office, absent that person having been charged with and convicted of said crime. It would be an absurd grant of power inconsistent with our entire conception of justice.

Luttig and Tribe, summarize their retort:

They conclude further that disqualification pursuant to Section 3 is not a punishment or a deprivation of any “liberty” or “right” inasmuch as one who fails to satisfy the Constitution’s qualifications does not have a constitutional “right” or “entitlement” to serve in a public office, much less the presidency.

While it’s arguably unjust that those who weren’t born US citizens and almost certainly arbitrary that those who have not reached the age of 35 are ineligible for the Presidency, those provisions have the virtue of being clear-cut. Section 3 lacks that virtue.

I can argue either way whether the Capitol Riot constituted a rebellion or insurrection. And there are arguably tens of thousands—or, hell, tens of millions if you stretch it—who gave aid and comfort to the participants. Given that insurrection is a criminal act, not a state of being, I just don’t see how we could possibly disqualify people who haven’t been convicted of that crime.

Luttig and Tribe disagree:

At the time of the January 6 attack, most Democrats and key Republicans described it as an insurrection for which Trump bore responsibility. We believe that any disinterested observer who witnessed that bloody assault on the temple of our democracy, and anyone who learns about the many failed schemes to bloodlessly overturn the election before that, would have to come to the same conclusion. The only intellectually honest way to disagree is not to deny that the event is what the Constitution refers to as “insurrection” or “rebellion,” but to deny that the insurrection or rebellion matters. Such is to treat the Constitution of the United States as unworthy of preservation and protection.

This is pure sophistry. The fact that a lot of people used emotionally-charged language to describe an event doesn’t make it so. And the countervailing fact that there’s a longstanding criminal statute called the Insurrection Act and that only a handful of the hundreds of people charged with crimes for their part in the riot were charged under its provisions is rather powerful.

To be clear: I think Donald J. Trump deliberately fomented violence in an attempt to steal an election. If he’s convicted in either the Federal or Georgia cases related to this attempt, I would be quite comfortable with judicial or Congressional officers declaring that he is barred from holding Federal office under the provisions of Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. But it would be bizarre, indeed, to simply declare him an insurrectionist absent his conviction.

Indeed, Luttig and Tribe seem to agree:

The Baude-Paulsen article has already inspired a national debate over its correctness and implications for the former president. The former federal judge and Stanford law professor Michael McConnell cautions that “we are talking about empowering partisan politicians such as state Secretaries of State to disqualify their political opponents from the ballot … If abused, this is profoundly anti-democratic.” He also believes, as we do, that insurrection and rebellion are “demanding terms, connoting only the most serious of uprisings against the government,” and that Section 3 “should not be defined down to include mere riots or civil disturbances.” McConnell worries that broad definitions of insurrection and rebellion, with the “lack of concern about enforcement procedure … could empower partisans to seek disqualification every time a politician supports or speaks in support of the objectives of a political riot.”

We share these concerns, and we concur that the answer to them lies in the wisdom of judicial decisions as to what constitutes “insurrection,” “rebellion,” or “aid or comfort to the enemies” of the Constitution under Section 3.

As a practical matter, the processes of adversary hearing and appeal will be invoked almost immediately upon the execution and enforcement of Section 3 by a responsible election officer—or, for that matter, upon the failure to enforce Section 3 as required. When a secretary of state or other state official charged with the responsibility of approving the placement of a candidate’s name on an official ballot either disqualifies Trump from appearing on a ballot or declares him eligible, that determination will assuredly be challenged in court by someone with the standing to do so, whether another candidate or an eligible voter in the relevant jurisdiction. Given the urgent importance of the question, such a case will inevitably land before the Supreme Court, where it will in turn test the judiciary’s ability to disentangle constitutional interpretation from political temptation. (Additionally, with or without court action, the second sentence of Section 3 contains a protection against abuse of this extraordinary power by these elections officers: Congress’s ability to remove an egregious disqualification by a supermajority of each House.)

Again, I thought Trump was rightly impeached for his actions on and leading up to January 6 and that the Senate should have convicted him and barred him from holding office in the future. The overwhelming number of Republican Senators, not surprisingly, lacked the backbone to do so.

Practically speaking, though, the fact that, were an election official to rule Trump ineligible under Section 3, it would immediately be contested in court, all the way up to the Supreme Court if necessary, means that the provision is decidedly not self-executing. And I would bet a whole lot of money that the courts would not let the decision stand—again, absent his being convicted in one or more of the above criminal cases.

100% agree James. This is fine from a pure theory perspective. However it’s completely unworkable in terms of practical implementation (and really fails to acknowledge that legal practice is bound by far more factors than just the law).

As with many other arguments, it’s ultimately wish-casting. And that’s dangerous because it prevents people from feeling the urgency to engage in the far more difficult work of organizing resistance at the ballot box.

The opportunity to use the 14th, sec 3 passed when the Senate failed to convict for the 2nd impeachment. If trump is convicted in GA or DC for his election overthrow attempts, I can see where Sec 3 could be instituted, but I don’t see a process for doing so.

I concur with James’ assessment. I see no way for that clause to be self-executing the same way the age limitation is.

Didn’t we see through the emoluments clause that the constitution is not self-executing?

As to the provisions of the age required for the presidency, I’m willing to bet all or most states have laws and regulations, enforced or applied through agencies, to register candidates for elections, however such processes are carried out. So if a 30 year old candidate not a citizen of the US tried to register, they’d be unable to do it.

In the end it’s a matter of enforcement, as noted above. No constitution or law is worth anything if the people tasked with enforcement won’t enforce it. See the electoral map Alabama passed, against an explicit SCOTUS ruling.

Ironcally, this theory has very similar vibes and structure to that of John Eastman and others who argued that McCain was not eligible for the Presidency which, like this, relied on a novel, self-serving, and extremely narrow interpretation of the Constitution with no historical precedent.

It’s interesting as an academic exercise but ultimately will go nowhere.

I don’t think the Constitution Police are coming.

In the end, Section 3 means whatever at lest five of the six Republicans on the Supreme court says it means. If it reached them as a question of whether Trump can run in the GOP primaries there’s a chance their “originalism” would lead them to follow what Luttig, Tribe, et al say is black letter law. If it’s the general and a question of whether Joe Biden or a Republican, even Donald Trump, gets to be prez, not a chance.

OT. I will never get used to this:

Gross.

I’m a bit confused by your assertion that a birth certificate is somehow 100% self-validating in a way that video of behavior during an insurrection is not. Have you forgotten the Birther nonsense so quickly?

Serious question: who was tasked with verifying that Barack Obama was, in fact, born in Hawai’i, for purposes of determining his eligibility to be President?

I used to like to point out to people that our oath to protect and defend the Constitution from all enemies, foreign and domestic, did not rule out that we might have to become enemies of our government. Of course, back then, the idea the government would objectively breach the Constitution was a bit far fetched. Thus the tricky part, I/we didn’t get our own interpretation of the Constitution.

Seems to me, these guys are wanting their own interpretation of the Constitution. Regardless of the 14th amendment, whether any element is self-executing without due process is itself a question challengeable to the SCOTUS.

Is this purely academic or is their intention to foment disruption by giving fog of war cover for election officials to try to keep Trump off the ballot?

@Andy: This seems to be a niche position by not one tied to ideology. Luttig and Baude, at least, are quite conservative. I gather Paulsen is as well. Tribe is the only liberal in the bunch, then.

@Kurtz: We’ll see what verbiage evolves over time. I’m liking Bluesky thus far, partly because it’s nearly identical to Twitter design/function-wise. It’s still a relative ghost town though; the vast majority of those I follow on Twitter aren’t on the new platform.

@DrDaveT: Candidates registering for office have to provide documentation of their citizenship and age. People can always claim that the documents are forgeries, I guess, but the election officials are the main enforcer.

I’m inclined to think the political will to make the effort to use this amendment just isn’t there but also that it’s a deux-ex-machina solution that takes the responsibility off the American voter. A friend of mine is talking about having buttons made that say “Don’t vote stupid”. He figures that everyone will want one because they think it refers to either candidate.

Also: can anyone decipher what JKB said?

@James Joyner:

I’m not making an ideological comparison between who is making the arguments, but the arguments themselves. I think the parallels of attempting to squint at the Constitution to invalidate a Presidential candidate are comparable between these two examples.

Sure, but you’d have to enforce a law against a Republican, and that is something up with which JKB and the rest of the MAGA continuum will not put.

@James Joyner:

Civics was a long time ago and I wasn’t a poli sci major. Who are these “election officials”, how many of them are there, who appoints/elects/chooses them, etc.? Who had the authority (hypothetically) to say “I am not convinced that Barack Obama is a natural born citizen of the US, and he is therefore not eligible to participate in the election in my jurisdiction”?

@DrDaveT: It varies from state to state but, usually, a Secretary of State is the chief election officer. I don’t know who, exactly, it is that screens the filings of presidential candidates each state. But there’s the thing: so far as I know, there was zero problem with then-Senator Barack Obama filing his candidacy for President because there was no serious question that he was a natural-born US citizen over the age of 35.

Still, if you wish in one hand and sh!t in the other, I can still predict which hand will fill up first with 99.9% accuracy (allowing for the possibility that it is possible for the wish hand to fill first).

Also, JBK is trying to obliquely speculate that the authors are shopping the notion of an act of force of sufficient scale to compel election officials to disqualify Trump. It’s a variation of “every accusation is an admission/confession.”

I was interested to see my old friend Jeff Sonnenfeld mentioned.

The First Amendment is almost entirely self enforcing. We are currently assisted by centuries of case law explaining it (or shaping it, if you like). What this 14th Amendment solution lacks is a body of caselaw to fill out the boundaries of “insurrection” or “aid and comfort.” The way we build that is to have some official asset it and then argue about it through the court system. It seems like Trump could be a pretty strong starting point.9

Let’s think this through…

Those formerly known as GOP decide to have Trump as their presidential candidate.

The inditements and trial(s) complete and Trump is found guilty of (fill-in-the-blank) and is sentenced to (insert number) of years in prison.

Trump decides to continue his run, incarcerated.

Trump becomes elected.

Dems decide to throw a penalty flag and… what?

Take it immediately to the supreme court to rule on the 14th Amendment concerns?

And with this court?

@Liberal Capitalist:

And if course there is the whole issue of standing, as in who can bring such a suit?

@Liberal Capitalist: The time to make the objection is much earlier than that – likely questioning his validity to appear on the ballot or be eligible as a write-in candidate.

And all that happens state by state.

Starting with swing-states, because who cares if he’s not on the ballot in California?

Steven L. Taylor: Self-executing is, as far as I can tell, a terminus technicus. It denotes the clause as a more “European-Style” legislation which is not created by case law but immediately applicable without any intervening secondary law or executive acts.

It does not mean that it won’t have to be adjudicated by a court, merely that the court will rule on whether the clause had been applicable to the case “all the time” (instead of only after the ruling).

It’s admittedly a bit ivory-tower (of the kind I love :P).

Its main relevance would be that courts adjudicating the clause would not be bound by the findings in a criminal case. This could be especially relevant in case a criminal conviction flounders on mens rea. While criminal law requires such, the clause could conceivably be ruled to not require mens rea, as “not being elected” is not a punishment (which would be subject to the strict limitations that govern use of state power against a citizen) but rather the removal of a privilege (which could conceivably be removed for much less severe acts as it’s the state setting the requirements for its own functioning).

It seems to me that what Baude, et al, have in mind is this scenario:

1. Some election official – a secretary of state, or even a county official – decides “Trump is ineligible, I’m striking him from the ballot”.

2. The Trump camp (the Republican party of that polity) sues in court.

3. Court (primary and/or appeals) whether Trump engaged in insurrection, etc, or at least “aid and comfort”.

4. This is a civil proceeding, not a criminal one, so the standard of evidence is merely preponderance of evidence.

5. The lower standard makes this all easy. Of course he did. He’s off the ballot.

I think that’s what they are saying. There is no need to rely on a statute or another court decision or even a vote for impeachment.