Congressional Gridlock And The Disappearing Swing District

There are very rational reasons behind the current gridlock on Capitol Hill.

Gridlock has been an issue in Congress many times in America’s past, but even to causal observers of politics it seems like it’s become far more of an issue in recent years than it has in the past. Reflecting our political culture as a whole, Congress, and especially the House of Representatives, has become more politically polarized on both sides of the aisle than it has in recent memory. Both parties have largely purged themselves of the middle ground, “moderate” Republicans and “Blue Dog” Democrats, and become far more represented by the most heavily ideological wings of their respective parties. This is one of the reasons that compromise has become such a dirty word in Washington on both sides of the political aisle and, as Nate Silver notes, much of it has to do with the fact that the vast majority of Congressmen are in districts where they face no real threat to re-electi0n:

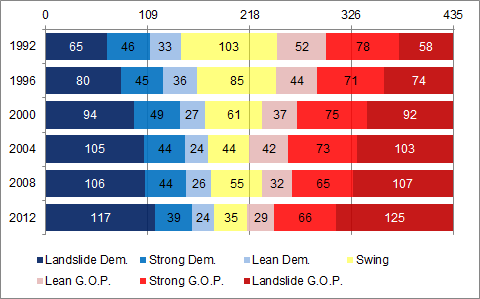

In 1992, there were 103 members of the House of Representatives elected from what might be called swing districts: those in which the margin in the presidential race was within five percentage points of the national result. But based on an analysis of this year’s presidential returns, I estimate that there are only 35 such Congressional districts remaining, barely a third of the total 20 years ago.

Instead, the number of landslide districts — those in which the presidential vote margin deviated by at least 20 percentage points from the national result — has roughly doubled. In 1992, there were 123 such districts (65 of them strongly Democratic and 58 strongly Republican). Today, there are 242 of them (of these, 117 favor Democrats and 125 Republicans).

So why is compromise so hard in the House? Some commentators, especially liberals, attribute it to what they say is the irrationality of Republican members of Congress.

But the answer could be this instead: individual members of Congress are responding fairly rationally to their incentives. Most members of the House now come from hyperpartisan districts where they face essentially no threat of losing their seat to the other party. Instead, primary challenges, especially for Republicans, may be the more serious risk.

Silver’s chart explains it all:

From 103 swing districts in 1992, we’re down to just 35 in the last election. If you add the “lean” districts in, we went from 188 potentially competitive districts, comprising just over 43% of the membership of the House to 128 potentially competitive districts, comprising only 29% of the membership of the House. Meanwhile, the number of largely safe districts (which I’ll count as Silver’s “landslide” and “strong” categories) for both parties went from a total of 250 in 1992 to 347 in 2012, a total of 79% of the membership of the House. Given the fact that incumbent re-election rates for the House typically run in the 90% range, this portends entering an era where the political makeup of the House is likely to only change at the margins and in which both political parties are likely to become more polarized as time goes on.

As Silver notes, the impact of all of this is rather obvious:

One of the firmest conclusions of academic research into the behavior of Congress is that what motivates members first and foremost is winning elections. If individual members of Congress have little chance of losing their seats if they fail to compromise, there should be little reason to expect them to do so. Republican leaders like House Speaker John A. Boehner may conclude that there are risks to their party if they fail to reach a compromise, as during the current fiscal negotiations. But as David Frum points out, the individual members of his caucus may bear few of those costs directly.

Meanwhile, the differences between the parties have become so strong, and so sharply split across geographic lines, that voters may see their choice of where to live as partly reflecting a political decision. This type of voter self-sorting may contribute more to the increased polarization of Congressional districts than redistricting itself. Liberal voters may be attracted to major urban centers because of their liberal politics (more than because of the economic opportunities that they offer), while conservative ones may be repelled from them for the same reasons.

In this environment, members of Congress have little need to build coalitions across voters with different sets of political preferences or values. Few members of Congress today are truly liberal on social issues but conservative on fiscal issues or vice versa.

There are many factors that play into this. The most prominent, of course, is the political impact of redistricting after each census. Most states still have a redistricting process that gives primary control over the process to the state legislature and when, as is the case in many parts of the country, the legislature is dominated by one party or another the rather obvious incentive is to draw district lines that benefit the political party in power. Indeed, this is a phenomenon that’s as old as the Republic. After all, the term “Gerrymandering” goes back to a Boston Gazette editorial denouncing new State Senate Districts proposed by Governor Elbridge Gerry’s Democratic-Republican Party. Even in states with nominally bipartisan redistricting procedures, though, you often see districts that are drawn in ways that would seem to defy geographic sense but make perfect sense once you realize that the goal of the drafters was to protect incumbents regardless of party. Here in Virginia for example, the redrawn 5th Congressional Districts stretches for 200 miles from the Virginia-North Carolina border to just outside the Northern Virginia suburbs, a total of more than 200 miles. It was part of a map that, when finally approved, essentially guaranteed a safe district for each of Virginia’s Members of Congress.

As Silver notes, though, the main problem that this high number of non-competitive districts creates is the fact that the Members in those districts have very different incentives from the ones that you might expect a politician to have. Instead of worrying about losing to a member of the opposing party in a General Election, their primary concern ends up being avoiding a primary challenge from the left or the right if they happen to stray from the party line. That’s why calls for compromise fall so often on deaf ears. There is more political risk for these Members of Congress in compromising than there is in holding the line. As long as that’s the case, then things are not likely to change on Capitol Hill.

For better or worse, there are very few solutions to this problem. Since the Constitution gives the states authority in the matter of redistricting, there’s very little that Congress or the Federal Courts can do about district lines that are drawn for partisan reasons. The one area of authority they do have concerns minority representation, especially for those states still requiring “pre-clearance” under Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. Ironically, though, the insistence on the creation of “majority minority” districts often ends up exacerbating the partisan nature of the district lines in a state rather than alleviating them. The only real solution would be for people at the state level to demand changes to the redistricting process. However, since the state legislatures also control redistricting for state legislative districts, the ability to influence those bodies to change the process seems limited to say the least.

Because of the gerrymandering you mention, a Republican House member has little to fear in the general election, but greatly fears being primaried from the right by Tea Party voters stoked by Norquist, Club for Growth (sic), et al money. What comparable situation exists on the left?

Without a doubt one of the most fundamental problems with the US politics is the nature of the electoral system. It goes beyond just partisan gerrymandering, although it would be better if non-partisan commissions drew the lines. The real problem is the dynamic created by single member districts and the primary mechanism itself. These institutional features sum together to create a situation in which Congress can have an approval rating in the low 20s and yet have a re-election rate in the 90s.

Solutions exist, but they are hardly political viable–indeed, these solutions are not even part of the public discussion.

(And getting a real discussion started is the place to start).

One thing about living in a small state is that you can’t gerrymander the districts. There has been a lot of turnover in my state for both the house and the senate over the last 12 years.

I think having a commission draw the lines would help, but I seriously doubt the commission is going to be completely non partisan either-but at least the districts won’t be entirely reliant on who is in charge of the state house when the census results come out.

What planet do you live on?

More “both sides do it” bullcrap from Doug. If I could roll my eyes any harder, I’d be afraid of them getting stuck like that.

Give me a couple examples of Democrats holding the line out of fear of being primaried by a zealot to their left, Doug. I’d love to see what you come up with. It doesn’t happen. The Democratic side of the aisle has been nothing if not pragmatic over the course of the last 4 years. More so than many on the left would like, but not enough for there to be any real threat of primary challenges.

This false equivalence is utter malarkey

@Steven L. Taylor: So let’s start a discussion. My naive thoughts are pretty much exhausted after term limits and non-partisan redistricting commissions with computer algorithms. (A version of which just failed here in OH.) You’re the PolySci expert, what would be the first three things you’d suggest, even if they are not politically or constitutionally viable? At this point we’re not trying to draft referenda, just blue skying. Thanks.

Complete nonsense, as per usual from Doug. While the GOP has indeed almost eliminated its moderates, this is not at all true of Democrats.

@bk:

Really, Doug can’t help himself. There is just an irresistible impulse to put in “both sides do it” in order to show “objectivity.” The main stream media has the same disease, too-falsus equivalencus.

Other than that, though, well written article, Doug. What’s becoming clearer still is that we now have an essentially parliamentary system in which the only way in which the government will get things done is to elect super majorities. The venerable “Inside the Beltway” ideal of men rising about “partisan bickering” to forge coalitions across parties just isn’t going to happen anymore-there’s an ideologically hard right party and a center-right to left party, and there is no incentive for those in safe districts to compromise.

Which means that we should forget about the idea of “cutting deals” with the Republicans. There will be no deals- only election victories. I expect the government to get absolutely nothing significant done till the Democrats gain a majority in the House and a super majority in the Senate. We should just get rid of the filibuster, too. The filibuster has turned into a super-majority requirement for most significant legislation and appointments ( It doesn’t technically have to be that way, but that’s what it’s become). In the current Congressional configuration, its become a tyranny of the minority. Time to bite the bullet, face reality, and get rid of this fusty obsolescent bar to majority rule.

An attempt to remedy some of the nutty districts had Florida voters approving an amendment in 2010 to require compactness for state and fed districts. Unfortunately it left the execution of the task to the same people who split their residence between Florida and Caymans, the same folks who gamed it in the first place.

I’m afraid nothing will fix this except the passage of time.

@gVOR08:

In terms of the semi-possible, I would go with nonpartisan panels for redistricting.

What I would like to see, which is part of the point of the post I just wrote, is that we would, as a country, acknowledge and understand that there is a broader set of options available than the way we do things.

At the moment, if I am going full pie in the sky, I would say adopt a mixed members proportional system like they have in Germany and that they adopted in New Zealand (see here for a pretty straightforward explanation: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JamSJ_yguqc)

NZ is interesting because it had the same system we currently have for electing congress (except they didn’t have primaries).

Mr. M, so long as you and your likeminded “moderate conservatives” continue to peddle the “both sides do it” routine, the GOP will grow more extremist than ever.

Radical Republicans desire criticism from anywhere on their left. This enhances their credibility in the Murdoch/talkradio media nexus.

The only criticism that has a chance of being heard must come from fellow Republicans. Unfortunately, all self-described “moderate” rightwingers have repeatedly shown they will ally with the extremists, though they know they are dangerously authoritarian, over the Democratic Party, which has shown a history of publicly repudiating their extremist wing.

@Rafer Janders: We do know that while the Democrats have gotten a tad more liberal in recent year, that the Reps have gotten substantially more conservative (see here for the political science). As such, you are right that a rigid assertion that both side are behaving the same is incorrect, and empirically so.

The Democrat Party embraces moderates. Just ask Tim Holden or Jason Altmire or Joe Baca.

Or Joe Lieberman.

Perhaps the districts themselves are the problem. Elect all house members in at-large statewide elections and see how they fall in line with the citizenry.

Alternatively, I have suggested before that we could have rules which draw congressional districts with no more than 6 or perhaps 8 corners, and no single boundary longer than twice the length of the shortest boundary, with a preference for natural geographic boundaries such as bodies of water or mountains. These sorts of constraints may result in a more rational approach.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Not sure what country you are talking about, but where I live in the U.S. Democrats are pushing to renew the “Bush” tax cuts, mandating purchase of health insurance from private companies and keeping Guantanamo Bay open.

@Tony W:

And shooting down amendments to shore up civil liberties abuses, to boot!

http://www.salon.com/2012/12/28/senate_fisa_vote_inspiring_display_of_bipartisan_commitment_to_ignoring_fourth_amendment/

@Tony W: I understand your point, and am sympathetic towards it. I am speaking here of the party in the aggregate (the data are at the link).

The Democratic Party has shed its more conservative members since the early 1990s, making the party more liberal in the aggregate.

Gentlemen, I give you the Illinois 4th Congressional District.

What are they thinking up there? So we have no politicians left who are skilled in the art of the deal? They’re going about this completely wrong. Of course, Obama doesn’t have the experience, but others do and know how it works. Here’s how: The president, speaker, Joe, and a couple of other power players get together in the far recesses of the White House (far away from Michelle for a few hours). Have a steak dinner and lots of brandy. Afterwards, handout some big Cuban cigars. (That’s sure to get Bill in there to help out). By midnight, you’ve got a deal!! Now who can argue with that ?

@Tony W:

That would make things worse. The big problem is that you need a ENORMOUS amount of money to run for Congress and that usually means that these large groups that pours money on local elections have a disproportional power.

A proportional statewide elections involves a bigger area and it´s more expensive.

@Steven L. Taylor:

To create more swing districts, the government would have to chop up many of the CBC and CHC districts that are designed to ensure that blacks and Hispanics win. I doubt if nonpartisan districting would survive a voting right act challenge in the courts.

Once again, people are discussing politics as if all of the voters are middle class whites.

@Ben:

Give me a couple examples of Democrats holding the line out of fear of being primaried by a zealot to their left, Doug. I’d love to see what you come up with. It doesn’t happen.

Well about 20 hours have elapsed since you posted this and needless to say Doug has produced no examples. I’m sure you weren’t holding your breath being familiar with his standard patter which is indeed old. Whilst gerrymandering undoubtedly helps both parties and it particularly helped Republicans in the last round since they controlled so much of it as a consequence of the 2010 elections, the drift to extremism is almost entirely a Republican phenomenon. The fact that Doug is unwilling to acknowledge this rather obvious fact tells us all we need to know about his bona fides.

@gVOR08: Doug, care to answer?

Show us this Tea Party on the left, please.