Income Inequality in Sports Mirrors Life

Steven Malanga looks at the distribution of income in professional sports and finds interesting parallels with the economy at large.

Steven Malanga looks at the distribution of income in professional sports and finds interesting parallels with the economy at large.

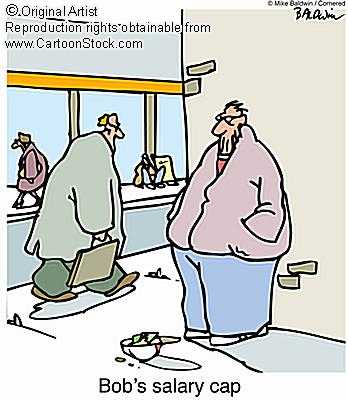

In the National Football League, which has a very rigid salary cap, teams spend upwards of 60 percent of their payroll on 20 percent of their players an 80 percent on their top 40 percent of players.

Is this fair? I suppose that depends on your definition of fairness. But by way of comparison, I took a look at how this income structure compares with household incomes in the United States. According to U.S. Census data, the top quintile, or 20 percent of households, captured about 51 percent of total family income, while the second quintile earned about 23 percent off all family income. Together, that amounts to about 74 percent of all household income. In other words, income is actually slightly more concentrated in the NFL than it is within our larger society, and there is a bigger gap between the richest and everyone else in football.

What makes this so astonishing is that the NFL has all sorts of mechanisms in place that we lack in our general labor market which are supposed to smooth out income inequality. For one thing, the NFL is entirely unionized, and we keep hearing (most recently from Barack Obama) that income inequality in America is in part a function of the decline in unions. The NFL also distributes talent to teams through a draft, which minimizes competition among employers for entry-level workers. No such check on bidding wars for the most talented exists within our general economy. The NFL has a cap on the amount of salaries it allows teams to pay, which presumably acts as a curb on salaries at the top of the wage scale. And players cannot jump to other teams until they have been in the league for four years, meaning that their employment mobility is far more limited than within our labor markets in general.

What is perhaps even more interesting is that what holds true in the NFL apparently is true within other major sports leagues, even though they all have very different collective bargaining agreements and salary structures.

Major League Baseball is a virtual free-for-all, with vast differences between team incomes and no salary restrictions. Yet “the top teams were paying between 66 percent and 77 percent of their salaries to only 25 percent of their rosters.” The NBA, which has a much softer cap than the NFL, has similar results: the team with the biggest payroll (the Phoenix Suns) “paid 68 percent of total salaries to just four of 14 players.”

What accounts for this madness among professional sports owners? Perry, writing about Major League Baseball salaries, opines that “above-average competence commands higher monetary rewards in an increasingly competitive” environment. Why? Because professional sports are quintessential human-capital industries, valuing the talents of individuals far more than anything else. The old saw about the new economy, that your assets walk out the door every night, is especially true in sports.

Still, it’s not as if the top players are capturing all of the rewards of the growth in professional sports, to the exclusion of everyone else. As MLB and especially the NFL have cashed in over the years, everyone’s share has grown. The total payroll of the Washington Redskins has doubled in the past five years. While the top players (who’ve changed over time) got a chunk of that gain, the median salary on the team also increased 85 percent to $855,000.

Something similar is going on in the rest of society, where the premium paid for talent has been rising, pushing up salaries fastest among those at the top even as everyone gains.

Of course, in big-time professional sports, even the poorest paid players are quite well off. That’s not the case in society at large. In athletics, the premium is on largely innate skills whereas success in the overall economy is more amenable to improvement by training and education.

[T]here are a few things a society may be able to do to narrow the income gap for some people, like ensuring that public schools do the best job possible preparing kids for college, so that those with the potential for college don’t get their aspirations quashed because they’re stuck in a bad system. But in a world in which not everyone is cut out to earn college or post-graduate degrees, as long as the economy keeps valuing the sheepskin so much it may be difficult to restrain income inequality. The goal in that case is to continue to ensure that the overall economy keeps growing so that everyone’s pie gets bigger, even if it’s impossible to micromanage how the pie is cut up.

After all, the NFL has fewer than 1,700 players, compared to a U.S. workforce of some 138 million, and the league employs a variety of rigorous mechanisms to redistribute income, yet it hasn’t done a very good job of smoothing out the rough edges of income inequality. They’re all getting richer in the NFL, just not at exactly same rate.

We shouldn’t overstate the parallels between sports leagues and the general economy. Still, the degree to which income distribution is similarly skewed despite the very different rules and dynamics at work is interesting.

Image: Cartoon Stock

Strange that the “CEOs make too much and hurt the poor” crowd never complain about the exhorbatant rates paid to top atheletes.

Could it be that “the racism of selective silence” is one reason?

Not complaining about who makes what-just noting the discriminating disparity of the left.

If free market and highly regulated/unionized markets produce similar results, is ‘similarly skewed’ the right phrase? Perhaps conforming to the natural state?