Madison, Will, and the Ambitions of the GOP

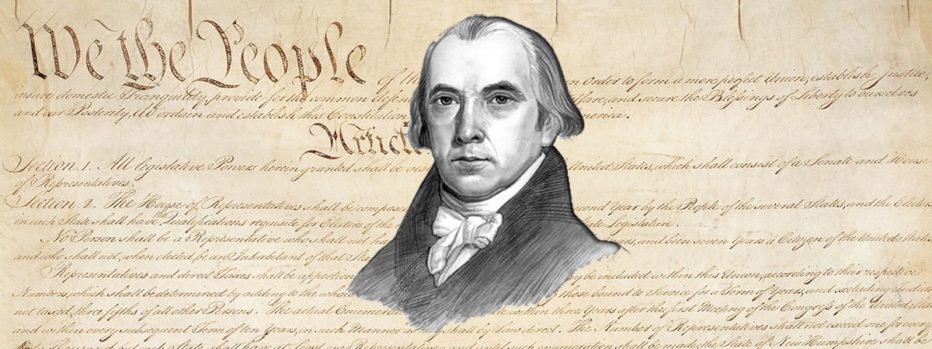

Madison was right about politicians and ambition. He just didn't see the how it would all play out.

George Will wrote the following a column already discussed here on OTB by James Joyner:

Ryan and many other Republicans have become the president’s poodles, not because James Madison’s system has failed but because today’s abject careerists have failed to be worthy of it. As explained in Federalist 51: “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place.” Congressional Republicans (congressional Democrats are equally supine toward Democratic presidents) have no higher ambition than to placate this president. By leaving dormant the powers inherent in their institution, they vitiate the Constitution’s vital principle: the separation of powers.

James notes in his post:

Quite right. On the late, likely unlamented, OTB Radio, Dave Schuler frequently noted that we had combined the worst features of separation of powers and parliamentary rigor. Even a decade ago, Congressional Democrats tended to vote lockstep against President George W. Bush and Congressional Republicans tended to vote lockstep with him. The phenomenon got much worse under President Obama and worse still under President Trump. There are a variety of reasons for this, mostly having to do with the purge of moderates from both parties, but the effects have been disastrous.

I started to write a comment on this at the post, but it was getting lengthy and I realized it should be even lengthier, so here we are.

We need to come to grips with the fact that the behavior we are seeing from congressional Republicans is actually what we should expect from our system now that the parties have self-sorted ideologically after the long effects of the Civil War (and Reconstruction specifically) on our parties finally faded in 1990s.* This is exceptionally important as what those of us of a certain age grew up with in terms of congressional party behavior is more the aberration than what should be expected. This seems counter-intuitive, but like the proverbial frog being slowly boiled, it is often hard to understand how our immediate surroundings are not always what they appear to be. Given the fact that the Republican party, in terms of the legislature (and, really, anywhere except the presidency), was largely not competitive in the southeastern United States from roughly the 1870s until the 1990s (with some exceptions) meant that a) the Democrats were a very large party that could muster votes (and controlled the chamber from Truman to Clinton), and b) there was some significant room for compromise between the GOP and Democrats within the chambers and between the legislature and the president. Deal-making and proverbial beer-having were easier in that context.

The last quarter century or so, however, has seen the parties re-sort ideologically and also an intensification of the geographical sorting of voters in terms of their partisan preferences (which is really important in a system in which geography plays an out-sized role in elections). As such, we should expect parties to treat the president as the leader of the party even moreso than in the past, and we are seeing the consequences of a bad leader. Madison, whom I have tremendous respect for, simply did not accurately predict how parties would form and then function in a legislature. It was beyond his experience when he wrote and theorized in the 1780s.

He was right that politicians are motivated by ambition, but the problem is assuming that they will be motivated, as he wrote in Federalist 51 (as quoted by Will above), by the ambition of retaining the power of the congress in face of encroachments by the executive. That may be true under the right kind of attack, but the reality is that a legislator from the same party as the president has every incentive to work with that president. This is because the main ambition that drives legislators is re-election and the secondary one is achieving certain policy goals. The president, as party leader, has a lot (not complete, but a lot) of influence over re-election, because the president can influence nomination. Just ask Mark Sanford. Ask Bobby Bright. And, likewise, the president is key in getting policies passed and enacted.

And yes, the president’s endorsement is not magic, as the Senate special election in Alabama proved, especially at the nominating phase. But it is rather clear that Trump’s popularity with the base means that Republican candidates want Trump’s support at the primary phase. This is a linking of ambition to congressional behavior that Fed 51 never envisioned. So Will’s consternation (and the laments of James and Dave above) that partisans vote with party is what we should expect. It is the way legislative parties work, even in separation of powers systems. Again: the aberration was the previous period. What we see now is what theory and practice would predict.

Will is being romantic in assuming that James Madison’s understanding of how a theoretical congress would function is the correct one However, note that Madison wrote the essay in support of ratification, and therefore its description of congressional politics was wholly hypothetical. We, as Americans, often fall into a similar romanticism because we are told in school about how separation of powers is allegedly supposed to work (I have been guilty of treating Fed 51 like a handbook of how congress is supposed to act in class, rather than as a persuasive essay trying to convinces people how Madison hoped it might act). But let’s focus on that fact that the existence of political parties means that the separation of institutional powers is not complete and total. Parties bridge the gap and create some degree of unity between the president and his co-partisans in congress. This changes what Madison was writing about, as he did not think that permanent groupings of legislators would persist, let along that they would be in clear and durable alliance with the person occupying the executive, but rather than temporary factions would form around specific issues and then dissolve.

Political parties are, therefore, essential institutions for understanding how representative democracies function. I cannot stress enough how much the Framers of the US Constitution did not understand this fact. Hence, one of the things that contemporary theorists of democracy understand, that Madison simply did not, is that institutions have to be structured with an understanding of how they affect party behavior, not just the behavior of individual politicians.

So, yes, we have more disciplined parties now–that is a reality that is going to remain in place. We are not going to return to the pre-Republican Revolution party system. What is worse (in my opinion), the current GOP has increasingly made a turn towards a reactionary approach to politics that has embraced white nationalism. This is an uncomfortable assessment that a lot of people are in denial about, but I don’t see how one can deny this fact, and it is not just about Donald Trump. Maybe this is rectified in 2020, but I have serious doubts at the moment.

But all of this is why Will is correctly arguing that the only options voters who oppose Trump have is to vote against Republicans, even if the voter considers themselves to be Republican. Really he is arguing that they should vote Democratic, but he can’t quite bring himself to say it. But the basic point remains: one cannot separate Trump and the GOP at the moment, even if we have a separation of powers system.

Beyond the politics of the moment, if we want better, more responsive government, there are a variety of things we could do (all of which range from the highly unlikely to the delusional-to-even-suggest, but truth is truth):

- Don’t elect a chief executive via a system wherein the person with less popular support can win the most powerful position in the country (if not the world).

- Expand the size of the House of Representatives so that it can better represent the size of our population. A US Representative is going to have a district of around 750,000 persons after the next census. That is an absurdly unrepresentative ratio or representative to represented.

- Change the way we nominated candidates. Primaries empower relatively small groups of voters and they short-circuit real third-party development. Those who want real third parties should want this.

- Elect the House in a proportional system. I would prefer the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system used in Germany and New Zealand. Others have suggested the Single Transferable Vote (STV) as used in the Republic of Ireland. If we want a House of Representatives then we need an electoral system that will produce representation of the population.

- Make it less possible for a minority of Senators, often representing a significant minority of the population, to block legislation.

There are other things I could note, but these are all key. 1 and 2 are unlikely, but maybe possible some day. 3 is unlikely because of the widespread belief that primaries are democratic. 4 is a dream. 5 may happen, but alone may not change all that much (there are further, more significant reform of the Senate I could raise, but they are all highly unlikely, whether they be changing the seat allocations per state or changing what the Senate can vote on–see German federalism for an alternative).

I not advocating simple majority rule. Indeed, the whole purpose of proportional representation is to increase the voices heard in government and to decrease the chances that only one segment of the population has power in policy-making. But the main problem with the US government at the moment is that it empowers a political minority to govern. Our government is insufficiently representative. A better electoral system would go a long way to solving that problem.

I would conclude, however, with pointing out that better institutions are not a panacea. I am not arguing that it solves all our problems, or necessarily produces justice and good public policy. What I am saying, however, is that at a minimum, if we actually believe in democracy in the basic sense of “government of, by, and for the people” we need our institutions to better reflect the panoply of positions in the country and, also, to not allow less that the majority to dictate major policy for the majority.

Democracy is hard.

At a minimum, we need to get over our romantic views of our Framers. We have two and a quarter centuries of data that they did not, both in terms of how the US system does, or does not, function, as well as a large number of other examples of democratic governance from which to draw understanding.

—

*It really is remarkable to see how specific historical events can have incredibly long-lasting effects. The fact that Lincoln was a Republican and, perhaps even more importantly, because the way Republicans in congress handled Reconstruction, there was century-plus affect on the party system. It is also rather noteworthy to recall the degree to which race has shaped our politics, as well as party behavior.

I agree with all of this. Additionally, Madison and company assumed that the status quo, loyalty to states and localities over the Federal polity, would remain the norm. We have long nationalized politics, such that everyone knows minute details about the President, most can name their U.S. Senators, many can name their U.S. Representative, and few can name their state legislators and local officials. So, Republican Congressmen are naturally going to be loyal to a Republican President when it’s simply no longer true that “all politics are local.”

@James Joyner: Exactly.

We forget that one of the reasons for the EC was concern that no one aside from Washington could have a national following. Ends up that was far from the case.

I agree with most of this, except for

The supermajority requirements force compromise or inaction — when the nation is deeply divided, it makes things stop, and that’s generally a good thing.

We shouldn’t have laws and judges that only one party finds acceptable. Our government should be responsive to all the people, not just the people who voted for the party in power.

There are lots of reforms that could be made to the filibuster, but in the end, I would want it to be stronger and to hit the end state faster (judicial nominations voted on within 90 days, but require 60 votes). I would also want to introduce it to the House of Representatives.

@Gustopher: I get your point, and really we need more fundamental reform of the Senate (IMO). But the reality is that what super-majorities do is not create compromise or some sort of over-arching agreement, rather than are just a minority veto.

True. What if we altered the rules so that as long as a filibuster was in place, no other business could be considered? Maybe that would pressure both sides? There is legislation that both sides consider essential, such as funding the military. Maybe that would force resolutions? Just spitballing.

@teve tory: I might could be persuaded that the filibuster of legend be allowed: that is, a mechanism that would require some effort by the opposition to maintain and that did, in fact, prevent further business.

The problem right now is that it has become a procedural tool that is far too easy to deploy.

I am not 100% against some sort of minority veto in some circumstances, but the chamber is currently uncontrollable without 60 votes. That is no way to run a legislature. It also obfuscates responsibility. This is partly how Trump gets away with blaming the Democrats for lack of legislation.

This is all gobbledygook because it doesn’t grapple with the reasons for Trump’s popularity with the GOP base and the general public. The only way it makes sense is if you pretend that GOP voters have suddenly become more racist, sexist, xenophobic, and hateful than at any time in the past AND you lie to yourself that Donald Trump’s approval ratings are in the mid-20s instead of the mid-40s. Oh, and you also have to blind yourself to the fact the economy is doing better than at any sustained point under either the Bush the Younger or Obama.

And please, spare the sermonizing about how the U.S. government is “insufficiently representative.” That’s not your problem. The problem is that it is FINALLY representing people and interests which had been ignored and excluded from our political discourse and instead of engaging with those people and interests democratically, you want to rig the system so you can go back to ignoring them.

For pete’s sake, we are three years into the Trump era and not only do you not understand why it is happening, you don’t even want to know. Hint: It’s not because the electoral system that worked for generations suddenly went haywire and needs to be fixed.

Mike

Proportional representation with SuperPACs and the First Amendment? That would be a nightmare. I’m all for a mixed system, but proportional representation would create something awful like the Brazilian Congress.

@Andre Kenji de Sousa:

Yes: I think that the US needs a more proportional electoral system. I always think you have something very specific in mind when you make this objection about proportional representation. Apart from the fact that Brazilian politics has a panoply of problems, I have never fully understood your objection.

@MBunge: Sigh. I have written about the electoral system and lack of representativeness for years–well before Trump was even a vague possibility.

Really, what part of the Trump agenda is that you a) like, and b) think is actually being instituted? The only significant legislation has been tax cuts that were not given to the disaffected, but to the wealthy. Is it tariffs? The border policies? The white nationalist rhetoric? The lies and BS?

Maybe you could spend some time and write out a cogent essay about what you think he represents and what you think he as accomplished. Because, quite frankly, you never really explain yourself, even when asked specific, reasonable questions.

@MBunge:

Who is it that are finally being represented? In what way, and by whom?

What concrete policies are examples?

@Steven L. Taylor:

I live in country that has proportional representation. Many people that likes proportional representation think that common people are likely to be affiliated with a given party. But they are not. Specially people in rural areas, they are pretty likely to want a politician from the area that they live, and they will not care if such politician is a good politician(During elections, specially in the suburbs and rural areas, Brazilian candidates for Congress will have their location as their only election plank).

People are more likely to vote against a crappy Congressman if they know that they are not going to lose public investments if they do so.

And yes, there is the problem of mega-churches – a megachurch with several locations can elect a Congressman only by saying to their followers that they should vote for a given candidate.

FPS can have all kinds of problems, but at least a candidate has to spend money in known and restricted geographic area, a Congressional District. In proportional voting campaigns can get really expensive.

I do agree with you that these institutional designs matter. A Proportional Representation system with extremely strong parties would result in something close to the Brazilian Congress. A FPS with extremely large districts and basically no control over campaign spending would result in something close to the American Congress. We all agree that these two are pretty horrible Congresses, so, that’s why I think that a mixed system that would guarantee local representation on politics with good representation of ideological interests is the best option. 😉

@Andre Kenji de Sousa: Well, I would note (as I think I have before), MMP is a PR system.

Not all PR systems are the same, nor do they all look like Brazil’s.

@Steven L. Taylor: Yes, but with the exception of Japan there is no country that is not a former British Colony that has FPS. And with both FPS or any proportional system the devil is in the details.

@Andre Kenji de Sousa: Do you mean FPTP?

I may be misunderstanding something, as Japan used to used the Single Non-transferable Vote (which was a multi-seat district system that I would not recommend) and they now use a Mix Member Majoritarian system.

I guess I would put it this way: in my professional opinion, single seat district, plurality systems have far more flaws from a democratic representativeness POV than do any multi-seat district systems.

Steven,

The problem with what you propose is that we only have two parties. A proportional & representative system along the lines of what you describe would be great in a multiparty system because then party platforms would actually represent constituent preferences. That is not possible with only two parties in a large and diverse country of 300+ million people.

Both parties are also growing less representative over time. They are not “big tent” parties anymore and their base of supporters is actually a small slice of the population. They manage to win elections not because they are any good at representing constituents, they win elections because voters are faced with a binary choice and they pick what they think the least-bad option is.

Absent a multi-party system where all the diverse views of America’s huge population would, in fact, be represented, your proposal would create a faux-representative system (actually a particracy in my view).

That is not a system that would bring political stability. Our two parties are pretty clear about their intentions to gain power and implement their policies by whatever means necessary. They would use their power to shove their narrow agenda down the throats of 300+million people. Then, at some future point, the other party will take over (thanks to the disgust of the independent voter switching sides), reverse everything, and shove their agenda down our throats.

That’s why the filibuster, the Senate, and the unrepresentative features in our system of government are necessary. If you want actual representation in our government (and I share your desire for that), then what we need is a multi-party system, not changes that reward our present entrenched and unrepresentative parties with additional power that they will only abuse.

Or, to put it another way, how do you intend to moderate policy or the winner’s political actions if you remove the present mechanisms we have for that.

@Andy:

The reason we have a two party system is because the institutions we have (single seat district, plurality winners, and primaries for nominations) establish incentives for only two parties. If we had different electoral rules, we would have multi-party system. If you would like an example of this in action, see New Zealand and its move from a system like ours to MMP (which meant from a two party system to a multiparty system after a change in rules).

This is one of the main things I have studies for that last quarter century: there is a direct relationship between electoral rules and the number of parties in the system. It is not the only variable, but it is a very important one. Much of my book on Colombia, and some subsequent articles, are about how candidates and voters change behavior in the light of new electoral rules. We have two chapters on this in A Different Democracy.

Exactly: and a different electoral system would produce a different party system–not immediately, but fairly quickly.

In a more proportional system, for example, there would be every incentive for the free trade Republicans to break off from the economic nationalist Republicans. Libertarians and Greens would have cause to vote not for Reps and Dems, but for their party of preference.

The entire point of criticizing the lack of representativeness in our current system, and to suggest different electoral rules, is to foster a party system that would be able to represent various issues.

We have two large parties because the math of our system, as reinforced by primaries, leads to two parties. A different electoral system creates new incentives for different political behavior for both candidates and voters.

To emphasize: “party platforms would actually represent constituent preferences” is exactly what I want to have in our politics.

@Steven L. Taylor:

Yup. It was called something like “distritão” in Brazil.

In my dilettante opinion I don’t disagree with you. I just think that you can have several problems with some proportional voting systems and I think that you should take in consideration the necessity of local representation.

@Steven L. Taylor:

In general, I agree – as I’ve said before as a life-long man without a party I truly would like to have one that actually approximates my preferences. But I don’t see how you get to a multiparty system absent remaking the entire Constitution which we both agree isn’t going to happen anytime soon.

So whatever reforms are made to our present system, we need to be cognizant of whether and how they advance or diminish the power of the two parties. In my view, the ability of the parties to implement their agendas should not be increased because of the reasons in my earlier comment.

@Andy: Well, electoral reform, depending on the route taken, does not necessarily mean constitutional reform (although MMP would).

The argument over what reform would create v. how likely reform is to happen are two different matters. I have no illusions about the probability of reform, but am at the stage where I think trying to stimulate conversation about a topic most Americans are utterly in the dark about is a worthwhile goal.

@Andre Kenji de Sousa:

Which MMP would do, if one is concerned about a district-level connection.

@James Joyner: I agree with all of this. Additionally, Madison and company assumed that the status quo, loyalty to states and localities over the Federal polity, would remain the norm.

That’s not a complete picture. Jefferson and Adams both considered equitable distribution of capital in a self-employment economy would act as a key restraint on political ambitions.