The USA v. the FARC

Newly disclosed details about the US role in Colombia.

The Washington Post has a very interesting, and lengthy, piece on the role played by the US in helping the Colombians combat the FARC and ELN in the last decade: Covert action in Colombia.

The Washington Post has a very interesting, and lengthy, piece on the role played by the US in helping the Colombians combat the FARC and ELN in the last decade: Covert action in Colombia.

First, some basic background.

The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (in Spanish the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, or FARC) are a guerrilla group that has been operating in Colombian since the early 1960s (and has its origins in the Colombian civil war of the 1940s and 50s known simply as La Violencia).* The FARC’s stated goal for many decades has been social revolution, i.e., the utter change of social, economic, and political life in Colombia. On the one hand, they have not been successful in that goal (nor will they ever be), but on the other, they have been able to persist over a lengthy amount of time as a serious thorn in the side of the Colombian state. The FARC was once only one of numerous such groups operating in Colombia over the decades, although it has long been one of the more prominent. Currently it is only one of two prominent groups in operation–the other being the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, or ELN).

The FARC has also long been funded by the cocaine trade. A decision was made in the early 1980s that, basically, if the gringos wanted to fund the revolution by spending literally tons of money to snort the white powder, the FARC were more than happy to oblige. The FARC also obtained a great deal of revenue from kidnapping. The group has had a history of attempted settlements with the government over the years, including a current peace process that is being negotiated in Havana. Past attempts were not especially successful. For example, an attempt to create a non-violent political party of the left, the Patriotic Union, for example, led to its members being systematically assassinated by right-wing paramilitary groups, which in turn has made the FARC suspicious of any attempt at entering civilian politics.** The UP was not, per se, an arm of the FARC, but the UP was an experiment, after a fashion, linked to the peace process in the sense that it was supposed to demonstrate a viable non-violent path for the left (which was linked to peace talks at the time). Additionally, an attempt in the late 1990s by President Andrés Pastrana to cede a Switzerland-sized demilitarized zone as a basis for negotiations eventually failed miserably.

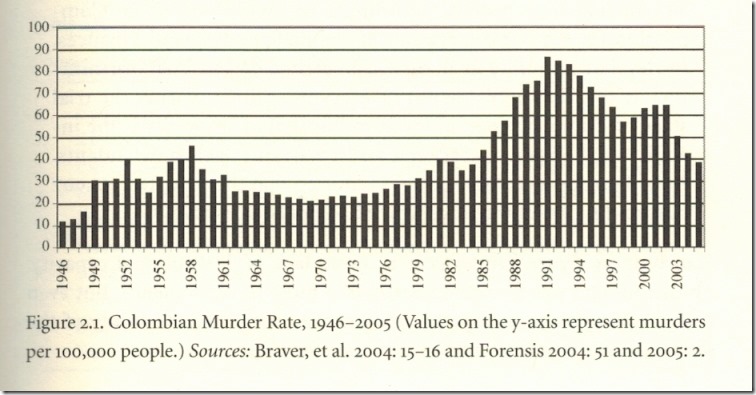

The 1990s and the early 2000s were especially violent and difficulty times in Colombia. Here are some charts from my book, Voting Amid Violence: Electoral Democracy in Colombia that underscore the situation:

A couple of things to note in this graph. First, the spike in the 1940s and 1950s was La Violencia noted above. The upward trend from the mid-1970s that peaked in the early 1990s was driven heavily by the drug war (and especially the conflict between Pablo Escobar and the Colombian state). Drug violence and growth in right-wing paramilitaries (which really start to be a major player in 1980s) help maintain the violence once Escobar was gone (he was killed in 1993), as well as fuel the spike in the early 2000s. Colombia violence, it should be noted, is a complex mix of guerrillas, cartels, paramilitary groups, and the state. It is also worth noting that those categories are not always mutually exclusive.

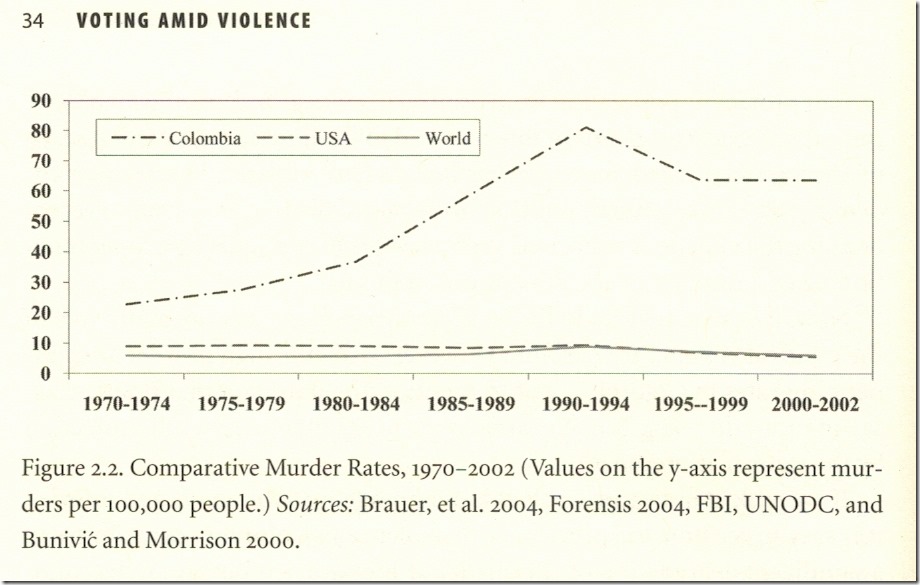

Here’s Colombia’s murder rate in comparative perspective:

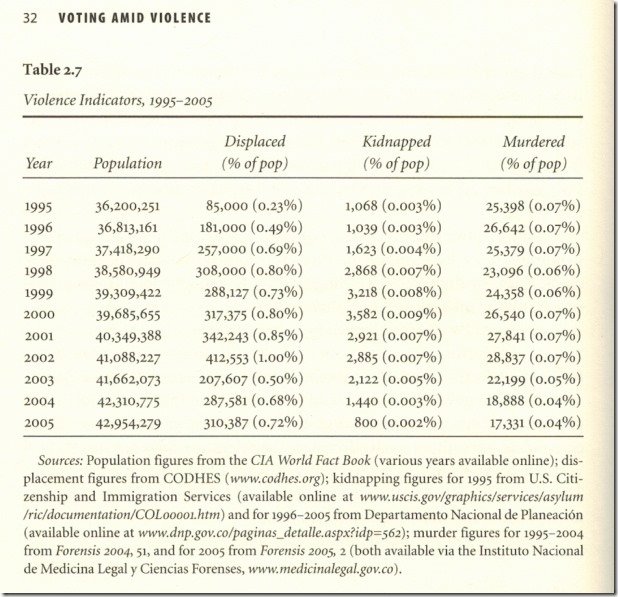

Some additional indicators can be found below:

The WaPo piece fills in some more recent figures, as well as providing some additional info:

Ok, enough background, on to what the WaPo piece reveals.

The article itself is quite through and it reveals two key pieces of information about US involvement that had not been previously public: the extent of US intelligence help in finding FARC and ELN leadership and the use of smart bomb technology to target those individuals:

The secret assistance, which also includes substantial eavesdropping help from the National Security Agency, is funded through a multibillion-dollar black budget. It is not a part of the public $9 billion package of mostly U.S. military aid called Plan Colombia, which began in 2000.

The previously undisclosed CIA program was authorized by President George W. Bush in the early 2000s and has continued under President Obama, according to U.S. military, intelligence and diplomatic officials. Most of those interviewed spoke on the condition of anonymity because the program is classified and ongoing.

The covert program in Colombia provides two essential services to the nation’s battle against the FARC and a smaller insurgent group, the National Liberation Army (ELN): Real-time intelligence that allows Colombian forces to hunt down individual FARC leaders and, beginning in 2006, one particularly effective tool with which to kill them.

That weapon is a $30,000 GPS guidance kit that transforms a less-than-accurate 500-pound gravity bomb into a highly accurate smart bomb. Smart bombs, also called precision-guided munitions or PGMs, are capable of killing an individual in triple-canopy jungle if his exact location can be determined and geo-coordinates are programmed into the bomb’s small computer brain.

It should be noted that US foreign aid to Colombia is not, in and of itself, news. Colombia has been for some time the third largest recipient of US foreign assistance behind Israel and Egypt. It was, if memory serves, moved to fifth place with the insertion of Iraq and Afghanistan into the mix. Regardless of specific rankings, the US has been spending a lot of money in Colombia for a rather long time (even if this is rarely commented upon in the US press—you would think we would, collectively, care more about the billions flowing southward than we do).

The usage of high-tech surveillance in Colombia by the US is not especially surprising, and ranks (to me) as not all that revelatory in the grand scheme of things. The US used high tech surveillance to aid the Colombians to track Pablo Escobar in the early 1990s,*** so it stands to reason that similar tactics would be used against the guerrillas—especially after US policy towards the insurgents shifted post-9/11. In the pre-War on Terror world, US policy was that aid was for fighting drugs, not guerrillas. However, after 9/11, US policy shifted, as underscored by the following statement from US Ambassador to Colombiam Anne Patterson (2000-2003): “the U.S. strategy is to give the Colombian government the tools to combat terrorism and narcotrafficking, two struggles that have become one. To fight against narcotrafficking and terrorism, it is necessary to attack all links of the chain simultaneously.”****

Of course, it is worth noting that the FARC and ELN were already on the US list of official terrorist organizations and, as already noted, the FARC was already involved in the drug trade. On one level, therefore, the shift in US policy was rhetorical.

As the WaPo piece notes, a main catalyst for the shift was especially acute after the FARC kidnapped three US contractors (and killing another):

The new covert push against the FARC unofficially began on Feb. 13, 2003. That day a single-engine Cessna 208 crashed in rebel-held jungle. Nearby guerrillas executed the Colombian officer on board and one of four American contractors who were working on coca eradication. The three others were taken hostage.

The United States had already declared the FARC a terrorist organization for its indiscriminate killings and drug trafficking. Although the CIA had its hands full with Iraq and Afghanistan, Bush “leaned on [CIA director George] Tenet” to help find the three hostages, according to one former senior intelligence official involved in the discussions.

The FARC’s terrorist designation made it easier to fund a black budget. “We got money from a lot of different pots,” said one senior diplomat.

US actions should also be understood in the context of the Uribe administration in Colombia. Uribe came to office with a clear hardline against the guerrillas and as one of the most pro-US Colombian presidents ever (and keep in mind, US-Colombian have generally been amongst the best in the hemisphere over time).

The intriguing part of the story is the use of GPS guided bombs:

Locating FARC leaders proved easier than capturing or killing them. Some 60 times, Colombian forces had obtained or been given reliable information but failed to capture or kill anyone senior, according to two U.S. officials and a retired Colombian senior officer. The story was always the same. U.S.-provided Black Hawk helicopters would ferry Colombian troops into the jungle about six kilometers away from a camp. The men would creep through the dense foliage, but the camps were always empty by the time they arrived. Later they learned that the FARC had an early-warning system: rings of security miles from the camps.

By 2006, the dismal record attracted the attention of the U.S. Air Force’s newly arrived mission chief. The colonel was perplexed. Why had the third-largest recipient of U.S. military assistance [behind Egypt and Israel] made so little progress?

“I’m thinking, ‘What are we killing the FARC with?’ ” the colonel, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said in an interview.

[…]

The colonel said he told then-defense minister Santos about his idea and wrote a one-page paper on it for him to deliver to Uribe. Santos took the idea to U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. In June 2006, Uribe visited Bush at the White House. He mentioned the recent killing of al-Qaeda’s chief in Iraq, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. An F-16 had sent two 500-pound smart bombs into his hideout and killed him. He pressed for the same capability.

The piece goes on to describe the process of adapting the technology to be used by the Colombia air force.

The number of successful airstrikes after that point in time is quite remarkable:

The article also discussed use of human intelligence, specifically the use of deserters:

The CIA also trained Colombian interrogators to more effectively question thousands of FARC deserters, without the use of the “enhanced interrogation” techniques approved for use on al-Qaeda and later repudiated by Congress as abusive. The agency also created databases to keep track of the debriefings so they could be searched and cross-referenced to build a more complete picture of the organization.

The Colombian government paid deserters and allowed them to reintegrate into civil society. Some, in turn, offered valuable information about the FARC’s chain of command, standard travel routes, camps, supply lines, drug and money sources. They helped make sense of the NSA’s voice intercepts, which often used code words. Deserters also sometimes were used to infiltrate FARC camps to plant listening devices or beacons that emitted a GPS coordinate for smart bombs.

“We learned from the CIA,” a top Colombian national security official said of the debriefing program. “Before, we didn’t pay much attention to details.”

There is more to the story, but this post is already extremely long. It is worth noting that the FARC has faced a number of setbacks in recent years, and many of them are clearly linked to these successful attacks (dating especially to the strike in Ecuador against Raul Reyes’ camp, which is also discussed in the article). There is also little doubt that these setbacks have been a major reason for the current talks. It should be noted that the current president, Juan Manuel Santos, was Defense Minister during much of this period. Santos will be running for re-election in May. In addition to the attacks and tactics discussed here, it is worth noting that Uribe (2002-2006, 2006-2001) took a very aggressive approach to the guerrillas when he came to office in 2002 and also was able to demobilize some of the paramilitary groups. The shift in the managerial nexus of the cocaine trade to Mexican cartels has also contributed to changes in Colombia.

Regardless of anything else, the story also illustrates a variety of issues pertaining to US capabilities and the synergy between intelligence and military capabilities. It also provides insight into activities in the ongoing war against terrorists groups in other parts of the globe.

—-

Note: all of the following are written for broad audiences (indeed, all were written by journalists if memory serves).

*One of the best book in English that I have seen on the FARC is Garry Leech’s The FARC: The Longest Insurgency.

**For anyone interested, I would recommend both Steven Dudley’s Walking Ghosts. Along these lines I would also recommend Robin Kirk’s More Terrible than Death.

***A great read on the war against Escobar is Mark Bowden’s Killing Pablo.

****I discussed the merger of the WoD and the WoT in an article for Stategic Insights back in 2005: “When Wars Collide: The War on Drugs and the Global War on Terror“.

Excellent post on an excellent article. As a side note, I’m loving the way long-form journalism is evolving to fit the web. The New York Time’s did really groundbreaking work with Snowfall. Now we’re seeing elements of it affecting the way other web journalists tell stories.

I think we’re learning how to use smart weapon technology effectively. It’s not a panacea, but when combined with competent local forces and good intel it does seem to be pretty effective at suppressing asymmetrical forces with minimal loss to our side.

Now to begin using it on all gun-owning Christians.

Oh wait, did I write that out loud?

It’s interesting in that it suggests that if we had competent partners in, say, Afghanistan, we could keep Al Qaeda there as well as Taliban forces on the defensive more or less indefinitely, while depriving them of their capacity to bleed us in return.

Unpacking that just a bit more, if Hamid Karzai focused a bit less on stealing aid money and a bit more on training a capable force we might just be able to prop the corrupt bastard up for a while. He’s an obnoxious buffoon, but he doesn’t make a habit of shooting school girls in the face, so by area standards he’s better than the opposition.

Thank you for this Steven. I had heard of FARC but with Iraq and Afghanistan had not really paid that much attention to it.

Pretty cool picture of the A-29 in it’s ‘Flying Tigers’ war paint, too. There’s been talk that they’re going to replace the old Warthog.

@michael reynolds:

it´s not so simple. You defeat the drug cartels in area or region then they simply move to another area or region. That´s basically what is happening in Mexico and in Rio de Janeiro. In Colombia, at least the FARC operated in sparsely populated areas, and that allowed the use of Military tactics that would be unthinkable in Mexico, Brazil, Peru or even Central America.

Al-Qaeda can move to countries where there are no partners available. On the other hand, any group of Armed Islamist is now claiming affiliation to Al Qaeda – they are a franchise, not a terrorist group.

Greetings:

So, the old USofA is getting more well-earned lumps of coal this Merry Christmas ???