Hollywood’s Changing Male Ideal

On screen body objectification is now equal opportunity.

For most of its history, Hollywood has demanded physical perfection from its female stars. Now, it’s the men’s turn.

Men’s Journal (“Building a Bigger Action Hero“):

Brando never did crunches. Al Pacino didn’t slurp protein shakes. Cary Grant had never even heard of burpees, BOSU balls, or human growth hormone. But not one of today’s leading men can afford the luxury of a gym-free life. You simply don’t get your name on a movie poster these days unless you’ve got a superhero’s physique – primed for high-def close-ups and global market appeal. Getting there takes effort, vigilance, and the dedication of the elite athlete: high-intensity training, strict diets, supplements, and hormone replacement. If that fails, there are always drugs. Today’s actors spend more time in the gym than they do rehearsing, more time with their trainers than with their directors.

Acting skill – even paired with leading-man looks and undeniable charisma – is not enough to get you cast in a big-budget spy thriller or a Marvel Comics franchise. “A decade or so ago, Stallone and Van Damme and Schwarzenegger were the action stars,” says Deborah Snyder, who produces husband Zack Snyder’s films: 300, Man of Steel, the upcoming Batman vs. Superman movie. “Now we expect actors who aren’t action stars to transform themselves. And we expect them to be big and powerful and commanding.”

Michael B. Jordan, who got his break as The Wire’s sensitive kid Wallace and raised his profile in last year’s Fruitvale Station, knows he needs to be able to bulk up on command if he wants to break into the A-list. “You’ve gotta be ready to take off your shirt,” he says, and he will as the Human Torch in next year’s Fantastic Four movie. “They want to blow you up and put you in a superhero action film. Being fit is so important. . . . The bar has been raised.” Even in the late Nineties, Hollywood’s biggest stars – Nicolas Cage, Keanu Reeves, Harrison Ford, Denzel Washington, Will Smith – were handsome Everymen, athletic but not jacked. Now even Tom Cruise and Bruce Willis, who is pushing 60, are more chiseled than they were in their prime.

[…]

For much of Hollywood history, only women’s bodies were objectified to such absurd degrees. Now objectification makes no gender distinctions: Male actors’ bare asses are more likely to be shot in sex scenes; their vacation guts and poolside man boobs are as likely to command a sneering full-page photo in a celebrity weekly’s worst-bodies feature, or go viral as a source of Web ridicule. A sharply defined inguinal crease – the twin ligaments hovering above the hips that point toward a man’s junk – is as coveted as double-D cleavage. Muscle matters more than ever, as comic-book franchises swallow up the box office, in the increasingly critical global market. (Hot bodies and explosions don’t need subtitles.) Thor-like biceps and Captain America pecs are simply a job requirement; even “serious” actors who never aspired to mega-stardom are being told they need a global franchise to prove their bankability and land Oscar-caliber parts.

Nor, interestingly, is the ideal that of Arnold Schwarzenegger in his prime.

Even the type of muscle has changed. “In the Eighties, it was the bigger, the better,” says director Tim Burton. “Think of that shot from Rambo of Sly holding the machine gun and the veins in his forearms bulging.” Actors rarely bulk up like that anymore; they’re all trying to be Tyler Durden.

Every trainer interviewed for this story cited Brad Pitt’s ripped physique in 1999’s Fight Club as an inspiration. Previously known for his lush, golden hair, the girls’ guy Pitt was reborn as Durden, a sinewy, predatory man’s man. “Brad Pitt in Fight Club is the reference for 300,” says Mark Twight, who trained the cast for 300. “Everyone thought he was huge, but he was, like, 155 pounds. If you strip away fat and get guys to 3, 4 percent body fat, they look huge without necessarily being huge.”

To get that hungry look, trainers stress calorie-conscious diets and exercises that pump up fat-burning metabolism. No actor can gain 10 pounds of muscle in a six-week period, but he can lean down to reveal the muscle underneath. Trainers talk about the “lean out” – the final, preshoot crash period when actors drop their BMI (body-mass index) to its bare minimum and unveil muscle definition.

But maintaining extremely low body fat for the duration of a multimonth shoot is nearly impossible and often dangerous: The stress can make an actor ill, damage internal organs, and make him susceptible to other injuries. Matt Damon, who dropped 40 pounds without supervision for 1996’s Courage Under Fire, got so sick that he was beset by dizzy spells on set, impairing his adrenal gland and nearly doing serious damage to his heart. Even in the best-case scenario, calorie deprivation can exhaust an actor, making him light-headed, distracted, and fatigued.

Since 5 percent body fat is nobody’s natural condition, fitness plans are geared to peak on the days of the sex scenes or shirtless moments. To prep for these days, trainers will dehydrate a client like a boxing manager sweats a fighter down to weight. They often switch him to a low- or no-sodium diet three or four days in advance, fade out the carbohydrates, brew up diuretics like herbal teas, and then push cardio to sweat out water – all to accentuate muscle definition for the key scenes.

The last-minute pump comes right before the cameras roll. Philip Winchester, the hero of Cinemax’s action series Strike Back, recalls seeing the technique for the first time on the set of Snatch: “Hundreds of extras were standing around,” he recalls, “and Brad Pitt would drop down and do 25 push-ups before each scene. I thought, ‘Why is he showing off?’ ” Then Winchester figured it out. “I realized he was just jacking himself up: getting blood flowing to the muscles. I’d always wondered, ‘How do actors look so jacked all the time?’ Well, they don’t. Now we ask: Is it a push-up scene? When I shot that Strike Back poster, I was doing push-ups like a madman, saying, ‘Take the picture now! Take it now!’ ”

A fat Superman would never fly. A pudgy Spiderman can’t swing. And an actor who can’t get jacked on deadline doesn’t have a shot at being a leading man in today’s Hollywood. Given the choice between acting chops and physique, producers and directors will often choose the better body. Today studios make bigger bets on fewer movies, aiming for blockbusters that are more expensive and complex than ever to make and whose trailers and posters rely on a ripped leading man. An out-of-shape actor can force a director to recast roles, reshoot scenes, or use CGI effects, often at great expense. Once he is signed on for a role and a production schedule is set, the actor is expected to do whatever he has to to get in the shape required of his character. Fitness budgets are baked into most contracts; studios typically pay for trainers, nutritionists, and even home-delivered meals. Some studios make a point to hire their own trainers so they can control the outcome.

[…]

Shoot days have gotten longer in film and television, so an actor’s endurance is key. A single injury can shut down a shoot and drive production over budget, so there’s increasing pressure for stars to stay fit, or perform injured if they don’t. “There are greater demands physically than 10 years ago,” says veteran action-film producer Randall Emmett (Rambo, Broken City, Righteous Kill). “You’re shooting 120 days for some of these movies now – 12 or 14 hours a day.”

If an actor is shooting on location, most trainers will find a local gym or devise stripped-down training plans around body-weight exercises, dumbbells, and bands. Big stars are a different matter. Studios will stop at nothing to keep them happy – and ripped. Bruce Willis’s weight trailer, which Teamsters drive to the set every day, is rumored to have cost $200,000. Downtime is the one constant on any shoot, so many actors improvise ways to keep fit on set. Nikolaj Coster-Waldau likes “body-weight exercises, no machines” while working on Game of Thrones so he can train on location. Russell Crowe likes to bike, if he does anything at all. Jonny Lee Miller runs to and from the set of Elementary. Jake Gyllenhaal prefers cardio, mostly biking and barefoot running. Since 2003, Robert Downey Jr. has practiced Wing Chun kung fu. Matthew McConaughey used to drop down and do push-ups in the middle of meetings, or whenever the Washington Redskins (his favorite team) scored – just so he could hit his daily goals. Jamie Foxx does push-ups in between brushing his teeth and shaving, as part of his morning ritual.

“For actors, it has to be a lifestyle,” says Peterson. “Train it, eat it, supplement it, sleep. That’s what you do. That’s just part of who you are.”

There is an easier way to go from flabby wimp to sinewy screen predator. Sometimes a superhero’s journey begins with the needle prick of a syringe full of human growth hormone (HGH), testosterone, or steroids.

“In Hollywood, the drug of choice is the drug that makes you look good,” says Strike Back’s Winchester. “It’s like the drug scene at a boarding school – it’s all available.” When actors ask about steroids, trainer Steve Zim tells them about the hair loss and zits, and “that usually ends the conversation in one second.” Steroids also produce rounder, water-retaining muscles instead of the lean, mean bodies currently in vogue. Testosterone and HGH are far more common, particularly for older actors, since lower levels of testosterone can make it impossible to retain muscle mass. “Over 40? I encourage getting tested,” says trainer Bobby Strom, “but there are some trainers who just go right to the testosterone, like they’re putting you on a multivitamin.”

Zim has seen the benefits of hormone therapy firsthand. “These people who look younger and fitter – a lot of them are using growth hormone and testosterone; the size comes from the testosterone, the virility and the youth come from the growth hormone.”

On set, actors swap tricks of the fitness trade – and the phone numbers of trainers and doctors who will prescribe testosterone or HGH, no questions asked. There are dozens of hormone-replacement clinics in and around Hollywood, and their business is booming. But there are significant risks: Hormone therapy accelerates all cell growth, whether healthy or malignant, and can encourage existing cancers, especially prostate cancers, to metastasize at terrifying rates. Testosterone supplements can lower sperm counts. For many, the risk is worth it.

So who on a movie set would be most likely to take a risk on something unproven that could cause bodily harm? The stuntmen, of course. Several actors we spoke to say the stunt guys introduced them to performance-enhancing drugs. It makes some sense: If you’re asked to body-double for Ryan Gosling without the benefit of his trainer and his personal chef, you’ll be tempted to take a shortcut, too. And if you’re jumping off buildings, battling ninjas, or swinging a battle-ax at ogres all day (or, worse, playing the ogre who gets bashed in 20 consecutive takes), you’ll see an upside to HGH’s accelerated recovery time.

[…]

For 300, the idea was to get the cast looking “like a gang” that had been training together since childhood. [Trainer Mark] Twight set up the gym as a gauntlet and played on actors’ insecurities by forcing them all to train on the same soundstage with their shirts off, watching each other.

“Male vanity,” he says. “Fuck – nothing more powerful. Thirty guys in a room, all vying to be alphas. Everyone had on leather underpants and a cape. Nobody wanted to be remembered as the Spartan with the muffin top.”

When Tom Cruise seemingly compared acting to fighting in Afghanistan (it turns out he did just the opposite) this is one of the things that occurred to me. While, obviously—as Cruise himself actually acknowledged—actors are just playing make-believe and getting well compensated for it, the schedule and physical preparation for these roles can indeed be quite grueling. More so, in many ways, than endured by the average soldier. The soldier more than makes up for that by putting his life on the line, enduring much longer separations from their loved ones, and doing it all for modest pay and little recognition.

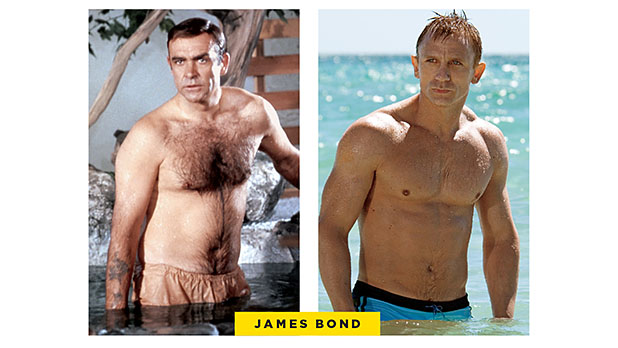

It is, indeed, amazing how rapidly the male physical ideal as depicted on screen has changed. Sean Connery, who is widely regarded as the definitive movie James Bond, was certainly in great shape in the early 1960s. But no more so than, say, an ordinary construction worker or ranch hand. Leap ahead to Daniel Craig, today’s Bond, and you’ve got the body of a world class athlete. (Then again, that standard has evolved just as rapidly if not more so. Compare the great NFL or NBA stars of even the 1980s to those of today and the difference is day and night. Training techniques and nutritional science have just transformed the realm of possibility.)

Aside from the cultural impact and the risks we ask actors and stuntmen to take to achieve this new ideal, some wonder about the impact on the craft:

Ever since De Niro remade his body for his Oscar-winning role as boxer Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull, physical transformation has been macho shorthand for an actor’s commitment – from Tom Hanks in Philadelphia to Christian Bale and Tom Hardy in, well, everything. Matthew McConaughey agreed to lose more than 35 pounds in his Oscar-winning role as an AIDS patient in Dallas Buyers Club, a show of faith that convinced co-star Jared Leto (who also won an Oscar for his role in the movie) to take a role in the film. “I knew Matthew had made the commitment to lose all that weight,” says Leto, who lost more than 30 himself. “It’s not just about how it looks. When that guy walks on set, people see him and say: ‘That guy’s not fucking around.’ That commitment compels you to deliver.”

Science is only making these body transformations easier and more common. For Spike Lee’s Oldboy, Josh Brolin had to embody a 20-year transformation from bloated alcoholic to killing machine; he gained 28 pounds in 10 days, and then lost 22 pounds in three days. “He took saline pills so the weight he gained was water and he could lose it faster,” says Lee. “De Niro talks about how hard it was to lose all that weight for Raging Bull, and how it took months. Josh lost his weight in, like, a weekend.”

Extreme weight loss or gain has become such a gimmick that lately, it seems many actors and fans are confusing body manipulation with talent. Actor Mark Strong, the star of AMC’s Low Winter Sun, says he is skeptical of this generational shift toward ripped bodies and extreme transformations. “I think a lot of young male actors are trying to prove how good they are by showing you how hard they’re working on their bodies,” he says. “It’s become almost synonymous with being a good actor. People want to quantify acting so that the acting looks awards-worthy.”

Sometimes that impulse to get fit can disrupt a film. Six-packs and bulky chests can look freakishly anachronistic in a prestige period picture: It’s not just that Tudor princes and Victorian lotharios didn’t have waxed chests and 12-packs – it’s that almost nobody had bodies like these until the last decades of supplements and fitness science.

“Can’t we just go back to when you didn’t have to do all this stuff?” James Franco gripes. “I look to Benicio del Toro. He’s not in the best shape but he still looks cool, man. He’s awesome.”

And true awesomeness is too ephemeral, too rare, to be achieved by effort alone.

“Either you have it or you don’t,” says Fast and the Furious star Rick Yune, “It’s not about Sean Connery’s fitness, or Liam Neeson’s muscles. You see Clint Eastwood point a gun – and you believe it. It’s not the physical. It’s what you put behind it.”

What Yune is really complaining about is this sense that studios see actors as bodies now – interchangeable in a global movie business that’s built more on brands than stars. More than ever, studios are building franchises around fresh, inexpensive faces with bodies that can fill a superhero costume.

“One of the reasons there are so few real movie stars is that there are very few who are distinguishable from one another,” says Nicolas Winding Refn, who directed Ryan Gosling in Drive and Only God Forgives. “Everybody can get a six-pack, so it has no value. Everybody starts to look alike. It’s the soul that makes you a movie star. Not your body.”

I’m not sure I buy it, really. Aside from the fact that Hollywood is more dominated than ever by action flicks and superhero movies, the notion that looks are substituting for talent more than they used to doesn’t hold up. If anything, we’ve raised the bar on both.

Frankly, while he lacks some of Connery’s charisma, Craig is a much more believable Bond than any of his predecessors. Why wouldn’t the elite of the elite superspies have the physique of a man who trains obsessively? Similarly, the Christian Bale Batman is much more like the character envisioned by Bob Kane—a boy obsessed by the killing of his parents who spent years honing his mind and body to fight crime—than the versions portrayed by Michael Keaton or, goodness knows, Adam West.

It is true that applying modern athletic ideals to actors portraying Tudor princes or ancient Spartan warriors is a bit absurd. Then again, no more so than having every single woman in the cast be fashion model gorgeous. These portrayals are in the realm of fantasy and escape, not reality. Nobody watching “300” thinks they’re viewing a documentary.

In real life there are no longer many strictly male jobs, nor strictly female jobs. Men and woman are essentially interchangeable in 99% of (non-acting) roles. We respond by fetishizing secondary sexual characteristics: big breasts and big lips on woman, big upper bodies on men. Beards, tattoos and piercings add to the male signaling.

It’s all interesting sociologically, but kind of desperate as well. “Look at me, I’m a man! Who sits on his ass all day poking a keyboard. But still a manly hunter of wildebeest!”

Workouts and training have changed. Spending hours at a gym pumping iron is out. Flipping huge tires, waving heavy ropes, climbing rope, pulling trucks with a rope is in. But some of this is a throwback and return to the physical training of gym classes years ago: jumping jacks, push ups, dashes, rope climbing, jump rope, climb the bleachers (that was the toughest), or stadium steps, etc. Look at some of the programs available on the internet.

One of the best workouts I got was doing some yard work a while back: digging holes, digging up stumps and shrubbery, sawing limbs: all done with hand tools. I was sore for three days. No way that I could get that kind of workout in a gym.

Sean Connery, who is widely regarded as the definitive movie James Bond, was certainly in great shape in the early 1960s. But no more so than, say, an ordinary construction worker or ranch hand.

If you want to have a yardstick for how things have changed, recall that Connery was an accomplished bodybuilder and Scotland’s Mr. Universe contestant in the 1950s.

Let’s not even talk about the hair.

It’s not on the level of ladies having to shave their legs, but you don’t see a Conneryesque torso of hairiness unless it’s being played for comedy.

My daughter recently came across the Sophia Loren in a bathing suit poster with the saying “everything you see I owe to spaghetti” and was surprised she was considered a bombshell since she had “chunky thighs” and “a thick waist”. Times have changed. Welcome to our world fellas!

@beth: As a woman, I find this development pretty damn sad. I don’t want women to have to risk their lives and health chasing after a physical ideal that most won’t ever meet. I don’t want men to have to do so, either.

@Keith Humphreys: That’s an interesting point. He’s obviously fit but just looks like a guy who does hard manual labor for a living.

@Tillman:

I recall reading somewhere, ages ago, that Connery’s shoulders and back had to be shaved.

I’m not sure I buy the idea that there’s been some sort of revolutionary change over the years. Cf., for example Carole Landis and Victor Mature in the 1940 version of 1 Million B. C. and that was more than 70 years ago. There was plenty of beefcake then as there is now.

And the actors did it the same way they do now: a combination of starving, training, and drugs. If there’s a big difference it is that the diet, training, and drugs are more sophisticated than they used to be.

The other big difference is plastic surgery but that’s a whole ‘nother subject.

As to Connery’s Mr. Universe competition, let’s compare apples to apples. Here he is in the competition.

@beth: Back in the day. Loren, Raquel Welch, Elizabeth Taylor, Kim Novak, Grace Kelly, and a few others were the “bombshells”. I used to have a 3 x 4 full poster from Raquel Welch’s ” 1,000. 000 B.C.” hanging up in my room. So did a lot of other teens.

And as far as yesteryear’s screen beauties are concerned, the “fashion silhouette” changes over time. The 1950s (primary era of Elizabeth Taylor, Marilyn Monroe, and Sophia Loren) was notable for having leading ladies who were more softig than they’d been in the 1940s or than they would be in the 1960s.

Many of the screen beauties of the 1930s were size 0s (and that’s when a 0 was a 0). Scarlett Johansson is a 4 (they claim 2 but I don’t believe it) and that’s a today’s 4. In 1954 Grace Kelly wore what was then a 10. That would probably be a 2 now.

@Tillman:

The ladies are shaving or waxing a bit more than their legs now.

@michael reynolds:

How do you define “strictly”?

If it’s 100%, I’d agree with you but, then, that was the case a century ago as well.

I personally dont get all the oohs and aws that Leonardo Di Caprio has received as a hollywood leading man. First he burst on the scene as basically a sub teenager and basically still looks that way. I dont get how or who thought that he possibly could portray a manly actor that people could believe. I watch his movies and think who cast this kid to play these supposed male roles…The actors of the time I grew up in looked more older than this new set of super young actors that we have out there today. A Sean Connery, Roger Moore, Clint Eastwood, and many more seem so much more adult than all these kids playing roles these days…

@Jim M: For whatever reason, men used to look a lot older back in the day. Connery was just 32 when he debuted as Bond in 1962. Moore was 36 when he took over the role in 1973. Craig was 38 when he took over the role in 2006. He’s 46 now.

@Jim M:

When you get older everybody else starts to look younger.

@Grewgills: There’s some of that. But, for example, Andy Griffith was just 34 when “The Andy Griffith Show” debuted in 1960. He looked at least 10 years older than that. Don Knotts was 36 and looked even older.

So true. James Franco? Zach Efron? Joaquin Phoenix? Seth Rogan? Give me a break.

I think the closest you get these days – in terms of a look – is Bradley Cooper.

i also think there’s a world of difference in the anti-aging treatments available now. Not every man getting a facelift or botox looks like Bruce Jenner. Many of them just don’t seem to age gracefully. like a lot of the old time movie stars did. Between hair transplants, botox and well-done plastic surgery I think many of the 30 something actors today are still going to look 30 something in 10-20 years.

@James Joyner: He was *considerably* more ripped when he was a body builder. http://images.t-nation.com/forum_images/auto/r/786×0/4/9/49dd4-universe_3rd.jpg

@al-Ameda: They basically don’t make movies for women any more. (I exaggerate, but only slightly) And especially not for women over 30. That used to be a prime movie demographic, but we’ve spent the last 20 years in a sort of vicious cycle where those women have kids later, so they’re more likely to stay home with a video, so Hollywood doesn’t make movies for them . . . the audience for movies in general skews young (almost all major movies are now made for males under 25), but especially the female audience. So it’s not entirely surprising that you’re seeing a lot more baby-faced male stars; that’s what appeals to the tween girls who actually go to movies by themselves.

And of course, female stars have always been baby-faced; now that women have careers, Hollywood has cast absurdly young women in senior roles, because God knows we can’t have a forty year old woman play the district attorney; 28 is already really too old for our audience.

@Megan McArdle:

Would disagree: seen a lot of “women’s movies” on Netflix recently and Meryl Streep and Dame Judie Densch are still big stars.

@stonetools: As I say, I exaggerate somewhat. But really only a tiny bit. Every few years, Meryl Streep or Diane Keaton or very occasionally Judi Dench gets to make a movie in which a woman-of-a-certain-age is the main character. Julia Roberts or Sandra Bullock makes that movie for fortysomething women, again every few years. And Cameron Diaz does the occasional woman-targeted comedy. But the number of movies targeted at adult women has steadily declined to a handful–so small that you can count the number of stars who reliably carry those movies on one hand. Hollywood has mostly abandoned that quadrant; movies targeted at it don’t play internationally, and there are no merchandising or licensing opportunities.

Meryl Streep and Judi Dench are indeed big stars. But Hollywood is not producing stars like that any more, because there are no roles for them to play in their twenties and thirties. It’s pretty striking that the most famous/respected stars (not character actors) are all over the age of forty; that certainly wasn’t true when, well, Meryl Streep was a huge star reknowned for her box office and her acting chops, and Diane Keaton was carrying Baby Boom with a male lead no one remembers. The young actresses of most of today’s movies are entirely disposable; if they spend too much time talking or otherwise developing a personality, it’s an unwelcome distraction from the important stuff that the guys are doing. Hollywood is making something like half as many movies as they used to 20 years ago, and almost all of them are geared towards an international market that is also heavily young and male, and wants to see explosions, not untranslateable jokes, or women talking.

The trend towards YA fiction may turn that around, which would be great; lots of comparatively meaty female stars in those. I just saw Hermione from Harry Potter in her first adult role, and she wasn’t good, nor blandly pretty in the way that Hollywood likes; I doubt she’ll last long. But Kristin Stewart and Jennifer Lawrence may well do okay. It would be a welcome change from the current trend where today’s starlets disappear at the age of 30.

@Megan McArdle

Film’s loss may be TV’s gain, eventually. The paydays for big movies are still higher than for top-of-the-line new TV series, but we’ll see how long that lasts – anybody who isn’t an important character in a comic book franchise series has got to be looking at what some TV series are offering and thinking it might be good to stretch their wings artistically. And we’ve seen McConnaughey and De Niro do it.

If you’re going by the picture you chose, he looks more like a gym rat than a world class athlete – most world class athletes have a tighter, less bulky look. That’s definitely true in sports where you can see the physique such as combat sports like MMA, wrestling (real, not WWE), boxing, and in T-shirt sports like basketball, tennis and Olympic weightlifting. And I suspect its true for most other sports as well.

No surprise, and I’m sure the Hollywood types would point out its irrelevant whether they look like world class athletes – what’s important is that they look like what people think world class athletes look like.

@george:

THIS.

Cary Grant began his career as a professional gymnast and had perfect balance. He didn’t really need a BOSU ball.

@Keith Humphreys: “If you want to have a yardstick for how things have changed, recall that Connery was an accomplished bodybuilder and Scotland’s Mr. Universe contestant in the 1950s. ”

I saw the movie ‘Deathtrap’ with Christopher Reeves, released in 1982 (*after* Superman). Reeves looked in good shape, but nowhere near where an action star would be now, or even later in the decade.