Reforming Ballot Access Laws

It may be time to rethink the way we make candidates get on the ballot.

Reacting to the news late last week that a Federal Judge had ordered Congressman John Conyers be placed back on a ballot after most of the signatures on his nominating petitions were invalidated due to the fact that the petition circulators were not registered voters, John Steele Gordon proposes getting rid of nominating petitions entirely:

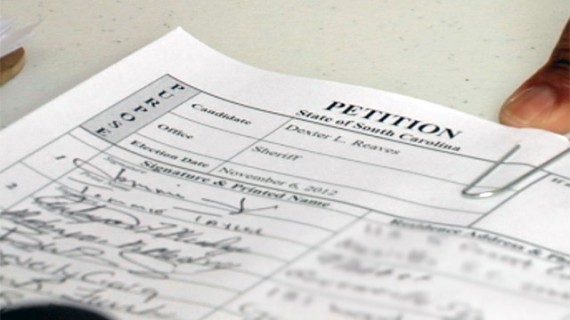

[N]ominating petitions are a truly dumb method for determining who gets a place on the ballot. They are very expensive, as volunteers (or often paid personnel) have to get a certain number of signatures of registered voters, obeying no end of persnickety rules about the proper form of signature, name, and address. The rule of thumb is that you need at least twice, and preferably three times, the legally required number of signatures to be sure of having enough valid ones. In Conyers’s case he needed 1,000, so he should have had 3,000 signatures to turn in. The reason you need so many is that your opponents, once you have turned in the petitions, will unleash their political lawyers hoping to knock you off the ballot on a technicality. You, of course, have to hire your own lawyers to defend your petitions. It is all an enormous waste of time, money, and energy and a lawyer’s relief act.

The supposed purpose of nominating petitions is to make sure that only genuine, politically viable candidates get onto the ballot, not guys wearing Uncle Sam suits. That is a legitimate concern. But the actual purpose of the nominating petition process is to make it harder for political insurgents to challenge the political establishment, which has the resources (and lawyers) to deal with the system.A far better, cheaper, fairer means of ensuring only serious candidates are on the ballot is the British system, which is also widely used in Commonwealth countries and in Japan. In Britain, a candidate standing for election to Parliament must deposit £500 (about $841) with the election authorities and he gets it back if he wins 5 percent or more of the votes. Some countries have much higher deposit requirements. In Japan, a candidate for the lower house of the Diet must deposit a whopping ¥3,000,000 (nearly $30,000) and win 10 percent of the vote to get it back.

In theory, the purpose of nominating petitions is supposed to be to ensure some level of ballot integrity by requiring people who want to appear on the ballot for local, state, or national office to demonstrate some minimal level of support for their candidacy. In reality, what ballot access laws in many parts of the country have become are a means by which the two major parties in general, and incumbents specifically, restrict third parties and challengers from getting on the ballot, or at least making it more difficult for them to do so. The Michigan law at issue in this case, which requires Congressional candidates to get just 1,000 signatures to get on the ballot. Given the fact that the population of Conyers’ district is some 700,000 people, and that he got more than 200,000 votes in 2012, one imagines that it wouldn’t be too difficult for Conyers to meet that target. The situation is quite different, though, for independent and minor party candidates. According to Ballotpedia, an independent candidate for Congress must submit at least 3,000, and no more than 6,000, valid signatures of registered voters in order to get on the ballot, three times as many as a candidate from ether of the two major political parties. In other states, the ballot access requirements are even more restrictive. In Virginia for example, a candidate for statewide office must submit at least 10,000 valid signatures, including at least 400 from each of the state’s 11 Congressional Districts. Other states are even more stringent, although there are some standouts. New Jersey, for example seems to be one of the few states where petition requirements for independent and third party candidates are actually lower than those for major parties candidates, at least when it comes to Federal offices. In general, though, even a short perusal of the nominating petition laws of the states leaves when with the inescapable conclusion that they are generally designed to make it harder for candidates to get on the ballot than aimed toward any legitimate goalof “ballot integrity.”

So, is Gordon correct in suggesting that we move toward a European/Japanese model when it comes to our ballot access laws?

On the surface at least, it’s a tempting proposal. For most candidates, it would be exceedingly easier to gather the cash needed to gain ballot access than it would to gather signatures to comply with often egregious petition requirements. Assuming the fee is reasonable, it’s something that a candidate should be able to fund out of their own pocket or by using money raised from supporters. The caveat, of course, is that “reasonable” part. It would be very easy for the powers-that-be to structure fee-based ballot access laws in such a way that make it hard for challengers and third party/independent candidates to get on the ballot just as they have structured the petition-based laws to do the same thing. And that’s really where Gordon’s argument falls apart. I can’t speak to how ballot access rules are created in other countries, but here they are drafted by state legislatures that are controlled by the two major political parties. As long as that’s the case, those laws are going to be used to the advantage of those parties.

Who cares? As the U.S. moves toward being a one party state, elections have become irrelevant. So why should ballot access matter? When 90% of elections are non-competitive and no election is about issues of policy or governance, then why not just maintain a system that allows the dominant party to maintain itself?

@superdestroyer: Proportional representation makes issues of policy and governance much more important, and decreases the importance of personalities, It also get’s rid of “every member of Congress is corrupt/evil/incompetent and should be thrown out, EXCEPT my congressman/woman”.

If you like local representatives, you can always go with mixed-member proportional representation. Combining the best of both worlds if you like.

This sentence no verb.

It’s worth asking what you mean by “ballot integrity”. What makes a ballot integrous? I would suggest that ballot integrity consists in having a small number of candidates (so that the selection problem is tractable), and not much else. It’s impractical to have 4,217 candidates for Lieutenant Governor, but I don’t think election commissions (or whoever administers these laws) have any business deciding who is a ‘real’ viable candidate and who is not.

If you move to a fee-based system, how do you limit the number of candidates? I don’t think you want to do it chronologically — i.e. the first 10 to pay their fee. I don’t think you want to have a bidding war — i.e. the ten who paid the biggest fee. I don’t see any way around having a secondary screening criterion, which is prone to end up being something like “number of signatures on petitions”. Anyone have a good suggestion?