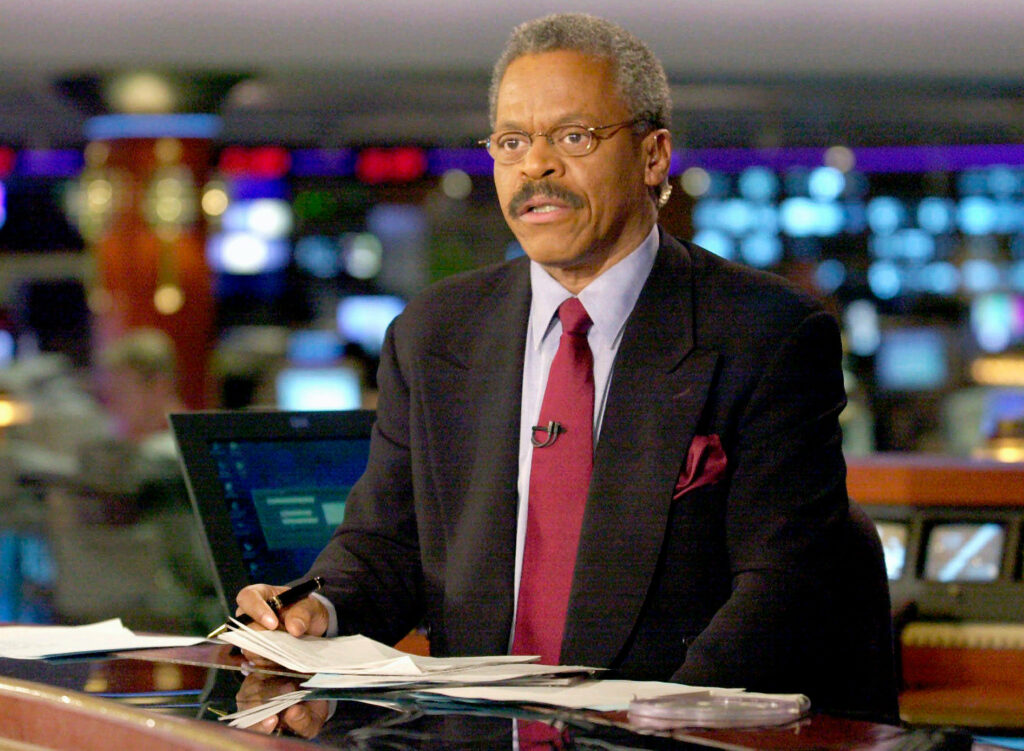

Bernard Shaw, 1940-2022

CNN's original anchorman is gone at 82.

Associated Press, “Bernard Shaw, CNN’s 1st chief anchor, dies at 82“

Bernard Shaw, former CNN anchor and a pioneering Black journalist remembered for his blunt question at a presidential debate and calmly reporting the beginning of the Gulf War in 1991 from Baghdad as it was under attack, has died. He was 82.

He died of pneumonia, unrelated to COVID-19, on Wednesday at a hospital in Washington, according to Tom Johnson, CNN’s former chief executive.

A former CBS and ABC newsman, Shaw took a chance and accepted an offer to become CNN’s chief anchor at its launch in 1980. He later reported before a camera hurriedly set up in a newsroom after the 1981 assassination attempt on President Ronald Regan.

He retired at age 61 in 2001.

As moderator of a 1988 presidential debate between George H. W. Bush and Michael Dukakis, he asked the Democrat — a death penalty opponent — whether he would support that penalty for someone found guilty of raping and murdering Dukakis’ wife Kitty.

Dukakis’ coolly technocratic response was widely seen as damaging to his campaign, and Shaw said later he got a flood of hate mail for asking it.

“Since when did a question hurt a politician?” Shaw said in an interview aired by CSPAN in 2001. “It wasn’t the question. It was the answer.”

Shaw memorably reported, with correspondents Peter Arnett and John Holliman, from a hotel room in Baghdad as CNN aired stunning footage of airstrikes and anti-aircraft fire at the beginning of U.S. invasion to liberate Kuwait.

“I’ve never been there,” he said that night, “but this feels like we’re in the center of hell.”

The reports were crucial in establishing CNN when it was the only cable news network and broadcasters ABC, CBS and NBC dominated television news. “He put CNN on the map,” said Frank Sesno, a former CNN Washington bureau chief and now a professor at George Washington University.

Shaw, who grew up in Chicago wanting to be a journalist and admiring legendary CBS newsmen Edward R. Murrow and Walter Cronkite, recognized it as a key moment.

“In all of the years of preparing to being anchor, one of the things I strove for was to be able to control my emotions in the midst of hell breaking out,” Shaw said in a 2014 interview with NPR. “And I personally feel that I passed my stringent test for that in Baghdad.”

Shaw covered the demonstrations in China’s Tiananmen Square in 1989, signing off as authorities told CNN to stop its telecast. While at ABC, he was one of the first reporters on the scene of the 1978 Jonestown massacre.

On Twitter, CNN’s John King paid tribute to Shaw’s “soft-spoken yet booming voice” and said he was a mentor and role model to many.

“Bernard Shaw exemplified excellence in his life,” Johnson said. “He will be remembered as a fierce advocate of responsible journalism.”

New York Times, “Bernard Shaw, CNN’s Lead Anchor for 20 Years, Dies at 82“

Bernard Shaw, CNN’s lead prime-time anchor for 20 years, who was also known for his steely coverage from Tiananmen Square in Beijing during the Chinese government’s crackdown on protesters in 1989 and from Baghdad at the start of the Persian Gulf war two years later, died on Wednesday. He was 82.

[…]

Known for his steadying influence at the anchor desk and from the field, Mr. Shaw had worked at CBS News and ABC News before he left the comfort of broadcast news to take a career gamble by joining Ted Turner’s fledgling Cable News Network in 1980.

He was one of the first Black anchors of a network evening news program, following Max Robinson, who became a co-anchor of ABC News’s “World News Tonight” in 1978.

Wolf Blitzer, a CNN anchor, recalled that Mr. Shaw, who worked with his reporting colleagues, Peter Arnett and John Holliman, remained in Baghdad for several days despite the danger of the assignment. “When he came back, I told him how nervous we were and that he was risking his life for all of us,” Mr. Blitzer said, “and he said, “It was a huge news story, so we stayed.'”

[…]

Bernard Shaw was born on May 22, 1940 in Chicago. His father, Edgar, was a railroad worker and house painter, and his mother, Camilla (Murphy) Shaw, was a housekeeper. Bernard had an early fascination with the news business: His father brought home four newspapers a day; he idolized the CBS News correspondent Edward R. Murrow; and as a teenager he found his way into the 1956 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

“When I looked up at the anchor booths,” he told Time magazine, “I knew I was looking at the altar.”

In 1961, while he was serving a four-year stint in the Marines, he was stationed in Hawaii and learned that Walter Cronkite, the CBS News broadcaster, was working on a story in Honolulu. He left messages for Mr. Cronkite that led to a meeting in the hotel lobby.

Mr. Shaw told The New York Times in 1988 that Mr. Cronkite said to him, “‘The key thing is to read, read.'” He added, “We’ve been friends ever since.”

After graduating from the University of Illinois, Chicago, with a bachelor’s degree in history in 1966, Mr. Shaw worked for local radio and television stations in Chicago until 1971, when CBS News hired him as a political reporter. His assignments included the Watergate scandal. He moved to ABC News in 1977 and became its Latin American correspondent, covering the mass murder and suicide of the Jonestown cult in Guyana.

At CNN, Mr. Shaw became one of the most prominent journalists hired to fulfill Mr. Turner’s daunting challenge: to quickly establish the credibility of a 24-hour start-up in a news business that was then known primarily for CBS, NBC and ABC’s half-hour evening news programs.

In a tribute to Mr. Shaw when he retired in 2001, Judy Woodruff, who anchored the “Inside Politics” program on CNN with him and is now a news anchor with PBS, said he had a “a manner and a voice that makes every word believable; the coolest demeanor in the hottest situations; the cut-to-the-quick interviewing style; and, at his core, a powerful combination of journalistic integrity and pure instinct.”

His judiciousness came into play in the aftermath of the attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan in 1981, when CBS and ABC erroneously reported the death of James Brady, Mr. Reagan’s press secretary, who had been wounded in the shooting. Mr. Shaw refused to make a similar announcement because the information that CNN had received was secondhand. Mr. Brady survived the shooting (and died in 2014).

We didn’t have cable when CNN debuted but I remember him from his earlier network appearances and certainly watched him a lot over the years. He was a pro’s pro.

Curious as to why he had retired so young—it was essentially required in Cronkite’s day but certainly wasn’t in 2000—I found a 2014 NPR interview with Michele Martin:

MARTIN: When did you decide it was time to retire? Or, how did you decide it was time to wrap up that phase of your life?

SHAW: Gnawing at me for years were the untold sacrifices that my wife, Linda – we’ve been married 40 years – and my daughter Anil and my son Amar made. I will never know the sacrifices they made so that I could do what I did. The countless weeks away from them, the missing of so many precious moments in a child’s and a wife’s lifetime, experiences. And it began to gnaw at us more, more, more. And I decided it was time to walk off the field when I was approaching my 61st birthday.

MARTIN: Are you glad? Is there a story you wanted to get your hands on?

SHAW: Oh, I’m very glad. I’m very glad.

MARTIN: Is there any story going on now you wish you could get your hands on?

SHAW: No. Occasionally the pulse increases when there are major stories going on, but I quickly get over that. You know, I did my time and I served the cause as much as I could. There are occasionally conversations that come up and people at networks will say, you know, you would be good for this.

But the right vehicle just hasn’t happened. And if it were to happen, I would return. I would return, but not full time, not full bore.

I remember, CNN, when I left, they did three separate one-hour tribute programs. One of them was Larry King for an hour. But another one was anchored by Judy Woodruff. And Gwen Ifill was there, Sam Donaldson, Frank Sesno, and a couple other journalists. And they played tapes and Sam Donaldson was making the point about the 1988 presidential debate that I moderated, and I interrupted him; I interjected.

I said, Sam, looking back over my career when I think about all the things that I did, but all the things that I missed within my family because I was out doing – I don’t think it was worth it.

His jaw dropped, and he just went apoplectic, and, how can you say that? How can you?

I said, honestly I’m telling you that after 41 years in this business, given what I missed, it was not worth it.

MARTIN: So what’s your advice then, for the people coming behind you? What is it – to not grab so hard for the brass ring? What would it be? What’s your advice?

SHAW: No, no. That’s such a personal judgment call. I would urge anyone – pursue your dreams. Don’t let anyone tell you what you cannot do. If you think you can, you will. If you think you can’t, you won’t.

MARTIN: So final thought would be, what? Would be, lean in as far as you want to lean in? Dream? Do what? What would your final thought – putting together everything you know, and everything you…

SHAW: Pursue your dreams, but know that it will cost you. Success will cost you. Physically and mentally it’s going to cost you. And I just pray and hope that you survive.

That’s certainly true. For men, especially, we tend to be defined by—and define ourselves by—what we do for a living. I glad that he lived another 21 years in retirement. I suspect he made the most of it.

The interview sheds a lot of light on his professional ethic as well.

MARTIN: When you got started in the business, what did you hope for? Did you have a goal for yourself?

SHAW: I wanted to be the best broadcast journalist I could be, and I wanted to emulate my idol – the first of two idols – Edward R. Murrow, and later, Walter Cronkite, who became a good friend for about 50 years.

MARTIN: When you say emulate, what do you mean? What qualities were you looking for?

SHAW: Strive for the writing abilities these men had, the clarity of thought they had, and their ability to communicate what they were seeing, what they were hearing, what they were witnessing, what they were feeling. And each of them had an opportunity to do that, given the wide venue of stories they covered, especially World War II.

[…]

MARTIN: Being cool under fire, just being – keeping it very calm, and very direct – and I just, you know, wondered what gave you the ability to do that?

SHAW: In all the years of preparing to being anchor, one of the things I strove for was to be able to control my emotions in the midst of hell breaking out. And I personally feel that I passed my stringent test for that in Baghdad. The more intense the news story I cover, the cooler I want to be. The more I ratchet down my emotions, even the tone of voice because people are depending on you for accuracy, dispassionate descriptions of what’s happening. And it would be a disservice to the consumers of news – be they readers, listeners or viewers – for me to become emotional and to get carried away.

MARTIN: You know, you’re kind of the anti-anchor monster. Because you know, the stereotype of like, an anchor head or anchorman, anchor monster, is somebody who’s just really – takes up a lot of room – you know that, right?

SHAW: I understand what you’re saying, but to me, more important than how I sound or how I look is how I think, how I write, how I communicate – that’s journalism. The other is BS. Using my initials in vain.

MARTIN: (Laughing) If you’re just joining us, I’m speaking with award-winning journalist and former CNN anchor Bernard Shaw.

Did you ever feel, as an African-American broadcaster, you had any special duty or responsibility to, you know, present yourself in a certain way, or to stand for something in particular?

SHAW: No. What I strove for was perfection, which was impossible to achieve. If I’m covering a story that’s of particular interest to African-Americans, I want to be certain that I cover that story as thoroughly as possible, as I would any other story. And being African-American, I would be the critic most critical of me if I failed to do the best job possible with that story.

That level of commitment to excellence would have made him a success in any profession he chose. And this is a fine tribute as well:

MARTIN: Well, you know, one of the things I always noticed about you – because I always would run into you on the, take for example on campaigns – you know, I actually spoke with one of your colleagues, Judy Woodruff, as you know…

SHAW: Ah, Judy, yes.

MARTIN: …With whom you shared the anchor chair for a number of years at CNN. One of the things she told me was, that one of the things that she always appreciated about you was professionalism. It was that there was never any kind of hint of sexism, or trying to, kind of, you know, play rank with her. Or just – she always felt like, the utmost respect from you. And I have to tell you, that you know, when I would run into you, on the – say, on a campaign trail or on assignments, you know, I always felt the same thing. Which is not the case with some of the – I’ll just say it – some of the senior men in the business.

What was your sense of like, working with people like me, who were junior to or coming up behind you?

SHAW: I have a responsibility. As a leader in my profession, I have a responsibility. To what? To share. I’ve been there. I know what it’s like. I know what it means to be Jukered (ph) out of a story. I’ve had stories stolen from me. I remember as ABC’s Latin America correspondent and bureau chief, I would average five trips a year into Cuba to cover various stories. And when ABC finally got a one-on-one interview with Fidel Castro, a man I’d covered for two years – who interviewed him? Who got off a charter jet from New York and strode in to interview him? Barbara Walters. So I’ve been there. And I was determined never to do that to any colleague. Never to be condescending.

MARTIN: But it’s not that you were just not condescending, it’s also what you were, which is very supportive and encouraging. You would say things to people like, you know what, you’re doing a great job. Or you’d say, you know what, that report was really crisp. And things like that. And I just wondered where that came from?

SHAW: I was a history major in school. That comes from the reality that you are in the next echelon. And those of us who are here have a responsibility to share what’s been shared with us. I wasn’t born doing this. So many hands, helping hands, are on my shoulders; I can’t count them. So I have a responsibility to pass it on. Plus, you’re a fellow human being, you know. Everybody listening to this interview will be dead in the fullness of time. The question is, what are we going to do while we’re here?

Not being a big shot when you’re very much a big shot is a hell of a trait. And, especially, not being a sexist at a time in which being condescending to women, let alone not treating them as professional equals, was simply normal, is remarkable. Further, growing up poor and Black and reaching the heights he did, he was certainly entitled to think he’d earned every bit of it on his own. Having the humility and self-awareness to understand that he’d had a lot of help along the way is rare, indeed.

The moment Dukakis flubbed the answer to Shaw’s question about his opposition to capital punishment was the moment I knew Dukakis had thrown away any chance he had to get elected President.

QFT.

@SC_Birdflyte:

There was nothing at all wrong with Shaw’s question. It was Dukakis’s response that caused the problem. I always wondered how Kitty felt.

Dukakis did it again, when Willie Horton’s surviving victims asked to meet with him: “I don’t see any point in talking to people.”

Anyway, RIP Mr. Shaw. You were a pro’s pro.

Shaw was one of the greats. A “pro’s pro” is very apt. No one working today compares sadly.

I like people who know when enough is enough, when they can push back from the table and say, ‘That was great, but that’s plenty for me.’ We tend to idolize the endlessly greedy – for money or prestige or power. What’s the point of chasing a goal when you are emotionally incapable of accepting that you’re there, you’ve made it?

@Michael Reynolds:

So you’re done with the whole book business then? 😉

@Andy:

I’ve tried to retire twice. It hasn’t quite taken.

But I do have a very clear limit to what I want. It’s a lot, more than I deserve, but it’s not open-ended.

It’s harder to accept that you didn’t reach your goals despite having given it your all and there really is nothing left in the tank. I struggled with it, I know others who struggled with it too. But in the end, we all let go. We have to.