Taxing the Very Rich

It's a lot harder than it looks.

Jesse Eisinger and Paul Kiel have a fascinating report at ProPublica titled “The IRS Tried to Take on the Ultrawealthy. It Didn’t Go Well.”

It’s based on the case of Georg F. W. Schaeffler, a German-born “auto magnate” and Duke-trained lawyer of whom I had not previously heard despite his having been the 30th richest individual on the planet a year ago (he’s now down to a paltry 96th).

In 2009, the IRS had formed a crack team of specialists to unravel the tax dodges of the ultrawealthy. In an age of widening inequality, with a concentration of wealth not seen since the Gilded Age, the rich were evading taxes through ever more sophisticated maneuvers. The IRS commissioner aimed to staunch the country’s losses with what he proclaimed would be “a game-changing strategy.” In short order, Charles Rettig, then a high-powered tax lawyer and today President Donald Trump’s IRS commissioner, warned that the squad was conducting “the audits from hell.” If Trump were being audited, Rettig wrote during the presidential campaign, this is the elite team that would do it. The wealth team embarked on a contentious audit of Schaeffler in 2012, eventually determining that he owed about $1.2 billion in unpaid taxes and penalties. But after seven years of grinding bureaucratic combat, the IRS abandoned its campaign. The agency informed Schaeffler’s lawyers it was willing to accept just tens of millions, according to a person familiar with the audit.

How did a case that consumed so many years of effort, with a team of its finest experts working on a signature mission, produce such a piddling result for the IRS? The Schaeffler case offers a rare window into just how challenging it is to take on the ultrawealthy. For starters, they can devote seemingly limitless resources to hiring the best legal and accounting talent. Such taxpayers tend not to steamroll tax laws; they employ complex, highly refined strategies that seek to stretch the tax code to their advantage. It can take years for IRS investigators just to understand a transaction and deem it to be a violation.

Once that happens, the IRS team has to contend with battalions of high-priced lawyers and accountants that often outnumber and outgun even the agency’s elite SWAT team. “We are nowhere near a circumstance where the IRS could launch the types of audits we need to tackle sophisticated taxpayers in a complicated world,” said Steven Rosenthal, who used to represent wealthy taxpayers and is now a senior fellow at the Tax Policy Center, a joint venture of the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution.

Because the audits are private — IRS officials can go to prison if they divulge taxpayer information — details of the often epic paper battles between the rich and the tax collectors are sparse, with little in the public record. Attorneys are also loath to talk about their clients’ taxes, and most wealthy people strive to keep their financial affairs under wraps. Such disputes almost always settle out of court.

There’s quite a bit more about the specifics of how Schaeffler and his team defeated the IRS by maneuvering. But I’m more interested in systemic issues. This is the key takeaway:

Most people picture IRS officials as all-knowing and fearsome. But when it comes to understanding how the superwealthy move their money around, IRS auditors historically have been more like high school physics teachers trying to operate the Large Hadron Collider.

For normal people, the IRS is a bogeyman: they simply have more expertise and resources than we can afford to bring to the table. For the very wealthy, though, it’s the reverse. It takes a dedicated public servant, indeed, to work for the IRS for a low-six-figure income if they have the talent to make ten or more times that working for the wealthy.

That began to change in the early 2000s, after Congress and the agency uncovered widespread use of abusive tax shelters by the rich. The discovery led to criminal charges, and settlements by major accounting firms. By the end of the decade, the IRS had determined that millions of Americans had secret bank accounts abroad. The agency managed to crack open Switzerland’s banking secrecy, and it recouped billions in lost tax revenue.

The IRS came to realize it was not properly auditing the ultrawealthy. Multimillionaires frequently don’t have easily visible income. They often have trusts, foundations, limited liability companies, complex partnerships and overseas operations, all woven together to lower their tax bills. When IRS auditors examined their finances, they typically looked narrowly. They might scrutinize just one return for one entity and examine, say, a year’s gifts or income.

Belatedly attempting to confront improper tax avoidance, the IRS formed what was officially called the Global High Wealth Industry Group in 2009. “The genesis was: If you think of an incredibly wealthy family, their web of entities somehow gives them a remarkably low effective tax rate,” said former IRS Commissioner Steven Miller, who was one of those responsible for creating the wealth squad. “We hadn’t really been looking at it all together, and shame on us.”[…]The vision was clear, as Doug Shulman, a George W. Bush appointee who remained to helm the agency under the Obama administration, explained in a 2009 speech: “We want to better understand the entire economic picture of the enterprise controlled by the wealthy individual.”

It’s particularly important to audit the wealthy well, and not simply because that’s where the money is. That’s where the cheating is, too. Studies show that the wealthiest are more likely to avoid paying taxes. The top 0.5 percent in income account for fully a fifth of all the underreported income, according to a 2010 study by the IRS’ Andrew Johns and the University of Michigan’s Joel Slemrod. Adjusted for inflation, that’s more than $50 billion each year in unpaid taxes.

The plans for the wealth squad seemed like a step forward. In a few years, the group would be staffed with several hundred auditors. A team of examiners would tackle each audit, not just one or two agents, as was more typical in the past. The new group would draw from the IRS’ best of the best.

That was crucial because IRS auditors have a long-standing reputation, at least among the practitioners who represent deep-pocketed taxpayers, as hapless and overmatched. The agents can fritter away years, tax lawyers say, auditing transactions they don’t grasp. “In private practice, we played whack-a-mole,” said Rosenthal, of the Tax Policy Center. “The IRS felt a transaction was suspect but couldn’t figure out why, so it would raise an issue and we’d whack it and they would raise another and we’d whack it.

The IRS was ill-equipped.”The Global High Wealth Group was supposed to change that. Indeed, with all the fanfare at the outset, tax practitioners began to worry on behalf of their clientele. “The impression was it was all going to be specialists in fields, highly trained. The IRS would assemble teams with the exact right expertise to target these issues,” Chicago-based tax attorney Jenny Johnson said.

Not shockingly, they pushed back. And, sadly, Congressional Republicans helped stymie the project:

The wealthy’s lobbyists immediately pushed to defang the new team. And soon after the group was formed, Republicans in Congress began slashing the agency’s budget. As a result, the team didn’t receive the resources it was promised. Thousands of IRS employees left from every corner of the agency, especially ones with expertise in complex audits, the kinds of specialists the agency hoped would staff the new elite unit. The agency had planned to assign 242 examiners to the group by 2012, according to a report by the IRS’ inspector general. But by 2014, it had only 96 auditors. By last year, the number had fallen to 58.The wealth squad never came close to having the impact its proponents envisaged. As Robert Gardner, a 39-year veteran of the IRS who often interacted with the team as a top official at the agency’s tax whistleblower office, put it, “From the minute it went live, it was dead on arrival.”

But some of the concerns were legitimate. The means of overcoming the massive advantages that the super-rich had were rather onerous:

The team sent wide-ranging requests for information seeking details about their targets’ entire empires. Taxpayers with more than $10 million in income or assets received a dozen pages of initial requests, with the promise of many more to follow. The agency sought years of details on every entity it could tie to the subject of the audits.

In past audits, that initial overture had been limited to one or two pages, with narrowly tailored requests. Here, a typical request sought information on a vast array of issues. One example: a list of any U.S. or foreign entity in which the taxpayer held an “at least a 20 percent” interest, including any “hybrid instruments” that could be turned into a 20 percent or more ownership share. The taxpayer would then have to identify “each and every current and former officer, trustee, and manager” from the entity’s inception.

Now, arguably, this is simply necessary. I’m by no means an expert on tax law or accounting but I’m not sure how you’d go about disentangling novel tax-avoidance schemes otherwise. But this is nonetheless a massive fishing expedition that poses substantial burdens on citizens. It also essentially reverses the presumption of innocence, forcing those being targeted to spend large sums of money to demonstrate that their business dealings are above-board.

Taxpayers who received such requests recoiled. Attacking the core idea that Shulman had said would animate the audits, their attorneys and accountants argued the examinations sought too much information, creating an onerous burden. The audits “proceeded into a proctology exam, unearthing every aspect of their lives,” said Mark Allison, a prominent tax attorney for Caplin & Drysdale who has represented taxpayers undergoing Global High Wealth audits. “It was extraordinarily intrusive. Not surprisingly, these people tend to be private and are not used to sharing.”

Tax practitioners took their concerns directly to the agency, at American Bar Association conferences and during the ABA’s regular private meetings with top IRS officials. “Part of our approach was to have private sit-downs to raise issues and concerns,” said Allison, who has served in top roles in the ABA’s tax division for years. We were “telling them this was too much, unwieldy and therefore unfair.” Allison said he told high-ranking IRS officials, “You need to rein in these audit teams.”

For years, politicians have hammered the IRS for its supposed abuse of taxpayers. Congress created a “Taxpayer Bill of Rights” in the mid-1990s. Today, the IRS often refers to its work as “customer service.” One result of constant congressional scrutiny is that senior IRS officials are willing to meet with top tax lawyers and address their concerns. “There was help there. They stuck their necks out for me,” Allison said.

The result of this multi-front pressure is hardly shocking:

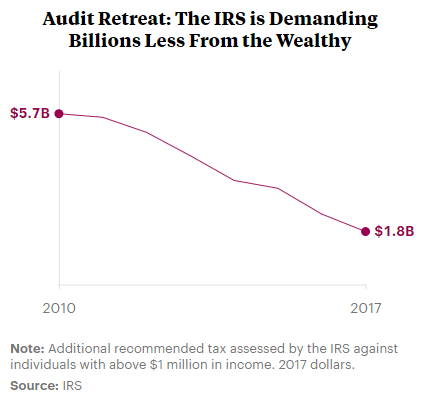

The lobbying campaign, combined with the lack of funding for the group, took its toll. One report estimated that the wealth team had audited only around a dozen wealthy taxpayers in its first two and a half years. In a September 2015 report, the IRS’ inspector general said the agency had failed to establish the team as a “standalone” group “capable of conducting all of its own examinations.” The group didn’t have steady leadership, with three directors in its first five years. When it did audit the ultrawealthy, more than 40 percent of the reviews resulted in no additional taxes.The inspector general also criticized the IRS broadly — not just its high-wealth team — for not focusing enough on the richest taxpayers. In 2010, the IRS as a whole audited over 32,000 millionaires. By 2018, that number had fallen to just over 16,000, according to data compiled by Syracuse University. Audits of the wealthiestAmericans have collapsed 52 percent since 2011, falling more substantially than audits of the middle class and the poor. Almost half of audits of the wealthy were of taxpayers making $200,000 to $399,000. Those audits brought in $605 per audit hour worked. Exams of those making over $5 million, by contrast, brought in more than $4,500 an hour.

Or, in picture form:

They add:

The IRS didn’t even have the resources to pursue millionaires who had been hit with a hefty tax bill and simply stiffed Uncle Sam. It “appeared to no longer emphasize the collection of delinquent accounts of global high wealth taxpayers,” a 2017 inspector general report said.

In recent years, the number of Global High Wealth audits has been higher — it closed 149 audits in the last year — but tax lawyers and former IRS officials say even that improvement is deceptive. A major reason is that the audits are much less ambitious. “They were longer at the beginning and shorter as the process moved on,” Johnson, the tax attorney, said.

Inside the IRS, agents seethed. “The whole organization was very frustrated,” Gardner said. “They were just really not sure what the hell their mission was, what they were supposed to be accomplishing.”

I simply lack the expertise to have a strong opinion as to how long or short these audits

- People ought to pay the taxes they owe,

- Higher scrutiny is warranted towards people making more money, and

- Government shouldn’t impose a higher burden than necessary on its citizens in enforcing its laws, whether the tax code or any other

Interestingly, Schaeffer comes across as a somewhat sympathetic figure here:

In 2008, Schaeffler Group made a big mistake. It offered to buy Continental AG, a tiremaker, just days before the stock and credit markets experienced their worst crisis since the Great Depression. Even as Continental’s stock price crashed, Schaeffler was legally obligated to go through with its purchase at the much higher pre-crash price. Schaeffler Group flirted with bankruptcy and pleaded for aid from the German government. The media began to pay closer attention to the private company and the low-profile family that ran it. German press accounts dismissed Schaeffler’s mother as the “billionaire beggar” for seeking a bailout and pilloried her for wearing a fur coat at a ski race while seeking government help.

No German government aid came. The Schaeffler Group teetered, and the family’s fortune plummeted from $9 billion to almost zero. Amid the crisis over Continental, Georg accepted his fate and took up a more prominent role at the company; he’s now the chairman of its supervisory board.

To pay for Continental, Schaeffler Group borrowed about 11 billion euros from a consortium of banks. At the time, Schaeffler’s lenders, including Royal Bank of Scotland, were desperate, too, having suffered enormous losses on home mortgages. They wanted to avoid any more write-downs that might result if the company defaulted on the loans. So in 2009 and 2010, Schaeffler’s lenders restructured the debt in a devilishly complex series of transactions.

By 2012, these maneuvers had caught the eye of the Global High Wealth group. Paul Doerr, an experienced revenue agent, would head the audit.

Eventually, the IRS discerned what it came to believe was the transaction’s essence: The banks had effectively forgiven nearly half of Schaeffler’s debt.

To the IRS, that had significant tax implications. In the wealth team’s view, Georg Schaeffler had received billions of dollars of income — on which he owed taxes.

The auditors’ view reflects a core aspect of the U.S. tax system. Under American law, companies and individuals are liable for taxes on the forgiven portion of any loan.

While it’s hard to be too sympathetic to someone born on third base, Schaeffler was a victim of a global recession. It’s strange, indeed, that having loans forgiven to avoid having to declare bankruptcy is considered “income” for tax purposes. But it’s a fundamental principle of our system:

This frequently comes up in the housing market. A homeowner borrows $100,000 from a bank to buy a house. Prices fall and the homeowner, under financial duress, unloads it for $80,000. If the bank forgives the $20,000 still owed on the original mortgage, the owner pays taxes on that amount as if it were ordinary income.

This levy can seem unfair since it often hits borrowers who have run into trouble paying back their debts. The problem was particularly acute during the housing crisis, so in late 2007, Congress passed a bill that protected most homeowners from being hit with a tax bill after foreclosure or otherwise getting a principal reduction from their lender.

Tax experts say the principle of taxing forgiven loans is crucial to preventing chicanery. Without it, people could arrange with their employers to borrow their salaries through the entire year interest-free and then have the employer forgive the loan at the very end. Voila, no taxable income.

The notion that forgiven debt is taxable applies to corporate transactions, too. That means concern about such a tax bill is rarely far from a distressed corporate debtor’s mind. “Any time you have a troubled situation, it’s a typical tax issue you have to address and the banks certainly understand it, too,” said Les Samuels, an attorney who spent decades advising corporations and wealthy individuals on tax matters.

And, returning to a familiar theme, it’s a lot more complicated when we’re dealing with people like Schaeffer:

But the efforts to avoid tax, in the case of Schaeffler and his lenders, took a particularly convoluted form. It involved several different instruments, each with multiple moving parts. The refinancing was “complicated and unusual,” said Samuels, who was not involved in the transaction. “If you were sitting in the government’s chair and reading press reports on the situation, your reaction might be that the company was on the verge of being insolvent. And when the refinancing was completed, the government might think that banks didn’t know whether they would be repaid.”This account of the audit was drawn from conversations with people familiar with it, who were not authorized to speak on the record, as well as court and German securities filings. The IRS declined to comment for this story. Doerr did not respond to repeated calls and emails.

A spokesman for Schaeffler declined to make him available for an interview. “Mr. Schaeffler always strives to comply with the complex U.S. tax code,” the spokesman wrote in a statement, saying “the fact that the refinancing was with six independent, international banks in itself demonstrates that these were arm’s length, commercially driven transactions. The IRS professionally concluded the audit in 2018 without making adjustments to those transactions, and there is no continuing dispute — either administratively or in litigation — related to these matters.”

Schaeffler’s lenders never explicitly canceled the loan. The banks and Schaeffler maintained to the IRS that the loan was real and no debt had been forgiven.

The IRS came not to buy that. After years of trying to unravel the refinancing, the IRS homed in on what the agency contended was a disguise. The banks and Schaeffler “had a mutual interest in maintaining the appearance that the debt hadn’t gone away,” a person familiar with the transaction said. But the IRS believed the debt had, in fact, been canceled.

Which, again, points to both the ability of the ultra-rich to shield themselves from taxes and of the government to claim that income existed when it doesn’t appear to on paper. It’s next to impossible for ordinary citizens to understand the issues involved because they’re just so different from our own financial circumstances.

For most of us, income is rather straightforward: we’re paid a salary, which gets reported on a W-2. Even for those of us who have small businesses on the side, it’s not all that complicated: we have income and expenses. The latter can get a bit questionable but there are reasonably clear rules about such things.

People like Schaeffler and their advisors are essentially making up complex transactions and the IRS is trying to retrofit existing laws to fit the mold.

Indeed, reading through the exhaustive ProPublica report—and despite my generous excerpting here, there’s a whole lot more in it—I’m not really sure Schaeffler and his people did anything wrong, let alone illegal.

I have often invoked Edward S. Corwin’s description of the Constitution’s “invitation to struggle” with regard to foreign policy. The tax code is essentially the same thing: people and corporations are naturally going to pursue every legal avenue for diminishing their tax liability. In the leagues Schaeffler and the megabanks who loaned him money play, those avenues are extensive.

Further, in Schaeffler’s case and many others, it’s even more complicated than that. The United States government naturally has a huge incentive to tax people like Schaeffler. But, because their money is earned through a complex web of international transactions, so do many other governments. So, naturally, the wealthy are going to do what they can to not only avoid as much taxation as possible but position their taxable income in the most advantageous jurisdiction possible.

I simply don’t know that it’s possible for the IRS to keep up. Or to know when the United States is getting its just share of the pie.

UPDATE: See my follow-up, “It’s Hard to Audit the Rich, So We Go After the Poor.”

So…..? We just give up on collecting taxes from rich people? This seems to be as much a story of Republican sabotage as it is of tax complexity. And the complexity that facilitates the avoidance is largely a product of Republican lobbying.

Piketty warns we’re moving back to a Gilded Age era of dominance by inherited wealth. This story is an example of how the wealthy are able to protect themselves politically. Many years ago J. K. Galbraith, the Paul Krugman of my youth, made a case for replacing the income tax with a VAT or something like it. He offered three compelling reasons. First, economists always prefer consumption taxes*. Second, the government needs the money. And third, removing the nominally progressive income tax, and the resentment that goes with it, would largely defund the Republican Party. I would love to see Dems run on a thorough overhaul of our absurdly complex tax system. There’s little point to maintaining a progressive income tax if nobody pays it.

_______

* Economists prefer consumption taxes as they wish to encourage savings, capital formation. Econ historically treats capital as the choke point in the economy. As we’re still recovering from The Great Recession, which was caused by the “savings glut” sloshing around and demanding higher returns than the market would bear, I sometimes wonder if this is still a valid assumption.

@gVOR08:

Nope. I think the rich ought pay what they owe. My point is that that’s a lot harder to determine than it would seem.

As I note in the piece, that’s certainly part of it. But it’s also a function of the rich having an army of accountants to outwit the tax code.

I’ve long preferred that route as well. It moves the incentives to the right place and it taxes the right thing: consumption. It also removes such dodges as the carried interest loophole.

I gather that the main arguments against a consumption-based tax are twofold. First, it’s not progressive. But I think we can fix that by excluding food, medicine, and the like. Second, that it creates incentives for hiding spending. But it’s not obvious that they’re any larger than the current ones for hiding income.

There’s more of us than they are of them.

A consumption tax on a billionaire is marginal at best. You’re assuming that a billionaire spends like normal folk. A car gets you to and from your job and to grocery stores; a yacht consumes diesel or gasoline and a modicum of groceries and crew wages and produces nothing. The lower down you go on the income spectrum, the more you see income spent on basics like food and housing.

Unless carefully weighted and progressive, consumption taxes are flat-out pro-rich.

Consumption taxes, depending on how they are constructed, can be very regressive. And, if flat, are definitively regressive.

It only poses substantial burdens because they made an active choice to complicate their finances in pursuit of hiding income. If they don’t like the burden created by these complex financial organizations, then there is a simple solution: simplify their finances and pay the resulting tax on their actual incomes, as they should have been doing all along.

This whole sob story about Schaeffler is the finance equivalent of a guy murdering his parents and then begging for sympathy on account of being an orphan.

It could be this way for the superrich to, if they chose to organize their finances that way. But then they’d have to pay their actual tax burden.

As for the solution to this, common law actually provides one already.

We need to create a federal escheat law. If someone sets up a scheme that makes it impossible to tell who owns something, then the solution is not to spend huge amounts of effort trying to figure out who the owner is, but rather declare it abandoned property that should be held in trust by the government until that owner becomes known.

Either the superrich person behind the scheme has to give up the property, or they have to come forward and lay out their ownership (in the process laying out precisely the information needed to determine their tax responsibility for it).

No amount of high-priced legal help can hide your money unless politicians have first written laws creating hiding places.

The super-rich – and way too many normal people – have been peddling the line that we are helpless, we’ll never collect from them, why even try? It’s b.s. It’s an attempt to spread a sense of futility. We’re being treated like children by these people, but more so by politicians of both parties though predominantly Republicans (of course) .

Stop writing tax avoidance pathways into law, hire better people at the IRS, raise penalties to the point where they draw arterial blood. Boom.

If a billionaire buys a fridge and pays a consumption tax on it (even if it’s a Viking full glass front fridge that costs $10k), it is by magnitudes far marginally less than a middle class person buying a basic model fridge at Best Buy – hugely so.

The super-rich are parasites and indicative of a failure of proper governance.

Bin Laden found that the world was not big enough to hide from the US government, but the super rich need not even budge: they give the government the finger at high noon, secure in the knowledge that they have their opponent outgunned.

Bin Laden got what he deserved, but the rich have done far more damage, and suffered little more than the inconvenience of (mostly failed) fishing expeditions.

Remember:

There’s more of us than they are of them.

@de stijl: And they exist at our suffrage.

In 1989, Leona Helmsley was castigated for saying, “We don’t pay taxes, only little people pay taxes.” Leona, we apologize for our cynical laughter; you were telling us the plain truth. I know someone who was a hobbyist who wound up selling some crafts he made at fairs and swap meets in his retirement years. The IRS caught him not paying income tax and seized a lot of his family property over a business netting about $12,000 a year. I also know a guy who works in NYC on “multigenerational wealth preservation.” He has a minimum $50 million NAV for his clients. He makes international arrangements that draw little government scrutiny for clients. That’s how things work in the real world.

@Slugger: Sadly true. And it’s not because that’s just the way things are, Republicans have worked hard to make it this way.

I think this gets to the heart of the common man’s support for a consumption tax: he simply cannot imagine how small a bite even the most lavish spending takes out of a billion dollars. I read once that a lifetime of five-star living requires about $200M.

And to continue:

I think the common man has no clue as to just what billions can buy. It buys opinion (through the media); it buys votes (through donations); it buys loyalty; it sets the agenda. And in the end, it buys democracy.

The American rich are behaving like the Italian and Greek rich and will achieve similar results. People need to stop normalizing these people’s behavior. These are sociopaths. They are mentally unhealthy individuals. When we see some morbidly obese person gorging until he vomits at an all-you-can-eat bar, we understand we’re looking at a person with mental health issues. These super-rich people still greedily swallowing every last dollar are no different: they are fcked up. And a country that lets these sociopaths design tax law is pathetic.

I read much of the article yesterday. My takeaway is that if the very rich, or the merely rich, can and do routinely avoid taxes, if they can and do habitually skirt the tax laws, then there should be a tax regime written specially for them.

I hesitate a bit to suggest this, because it appears to violate the very important principle of equality before the law. This being that the law must be the same, and applied the same way, to all.

But we don’t regulate home freezers the way we do industrial freezers, or a private car the same way we do taxis. A difference in principle demand a different law. Besides, any tax law would apply blindly considering only wealth, not other factors.

I was basing a lot of my arguments on “marginal”, when I should have been using “proportional”.

Assume you make a $100k income. A dollar to you is proportionally the same as 1 cent to a person who makes $10 million. Your $400 dollar fridge from the discount outlet would seem proportionally to the $10 M person as $4 dollars.

The main reason to think that the rich are not our betters is that they have no experience in what it takes to just get along day-to-day. They are effing clueless.

I had to gauge whether buying the potatoes vs. bologna was the better purchase. I could not afford both.

Lucille Bluth on $10 bananas:

https://youtu.be/Nl_Qyk9DSUw

@gVOR08:

It’d cool if they acknowledged that. One would think that if you existed at another’s mercy you would be super cool and deferential, but no. That doesn’t happen here. The rich do not appreciate nor understand how they became rich, and assume it is their right.

@de stijl:

On the right track, but the reality is even harsher. Take away taxes from your $100k and then all the expenses you cannot avoid. That’s what you have to spend on “luxuries.” Do the same for the guy with $10M. A quick back-of-the-envelope calculate brings me to 6k:1, instead of your 100:1.

@Kit:

I was edging our less enlightened friends into this argument slowly.

They’re convinced that “boot strappiness” and a positive attitude is a sure track to independent wealth. Those traits also make you susceptible to voluntary wage slavery which our economic system is based on.

@Michael Reynolds: Exactly! Chasing the money at the audit level is chasing the horse instead of closing the barn in the first place. The problem presents at the statute/code level. That’s where it gets solved also.

Unfortunately, Congress is full of people who have written statutes and codes for the benefit of themselves and the moneyed interests that finance their election rather than the nation. Not sure how you go about fixing this.

@Kit: You do realize that comparing the uber rich to bin Laden makes the solution to the problem… ummmm… (how shall I put this?)… problematic?

I wish I understood it more, but I read a lot of Noah Smith and he loves the Land Value Tax

It’s seen use in Pennsylvania as well as other places. My pet theory would be to look for fines and other lawbreaking among the crowd with the highest value deductions and slash their deductions by a third or more. Say break two or three laws, you don’t get to take full advantage of the tax system. Make the standard deduction exempt from this process so this doesn’t way heavily on lower brackets.

@The abyss that is the soul of cracker:

Cracker, you are nothing if not delicate. And you are correct. But I stand by my statement, and feel that the OTB crowd can judge me. My basic argument is the bin Laden was a slap in the face, but that the new oligarchy is a heart attack: an existential threat.

@Just nutha ignint cracker:

Guillotines?

I am not anti-capitalist. Capitalism provides many societal benefits. It provides for aggregate demand; for which, I heartily approve.

It is also nasty and destructive, and exploitative.

Both are true.

We are dozens of comments into this, and we’re bandying about the idea he proposed and not him. No one is dogging the author.

You have no idea how cool that is.

Iam very pessimistic about attempts to tax the rich. First wealthy people today control more wealth than they have for quite a while. They own a larger share of our wealth and income than we have seen since the 20s. They may control even more than folks did in the 20s as they have become so good at hiding their money. Next, they now actively control our media, our think tanks and our government. They used to mostly stain the background and buy influence, now they are in office. They make sure the tax laws are written to favor themselves, and they make sure that the IRS doesn’t have the resources to go after them.

Last of all, the modern wealthy person has a whole literature and philosophy written to support their amoral behaviors. Mind you I am not saying they are all that way, but when they are they can self justify their behaviors and they are supported by many of the non-wealthy. We end up with the Perdue pharmaceutical killing promoting the drugs that kill thousands and disable hundreds of thousands. We get the Shkrelis of the world.

This will be very difficult to change since the wealthy are in control. I honestly dont know what will change it.

Steve

(i.e., Taxing The Rich)

It’s actually really easy and we it did for decades after WW2 back when our economy and our growth rate was the envy of the world. Taxing The Rich is actually easy and it does make sense. Please, investigate tax rates over time and economic outcomes. That would be awesome.

(I’m the person that highlighted we’d not dinged Joyner, … and then I just dinged Joyner.)

After Reagan’s reforms, when have we been the envy of the world economically?

For those advocating for a consumption tax, keep in mind that it won’t help unless passing money to your heirs is classified as consumption. We need to come to grips with inheritance as an antisocial behavior, and figure out an equitable way to allow family farms without enabling parasitism.

@DrDaveT: In principle I’m against the rich passing along vast sums to their kids. But it does actually amount to a death tax. Why should a child whose rich parent lives to 80 get the benefits that come with wealth while a child whose rich parent dies at 40 be twice punished?

@Michael Reynolds: In the spirit of Kit’s answer on the same issue, that’s certainly one solution. And while I have apologized to the folks here for not helping Huey and Angela burn the suckah to the ground back in the day, I still have reservations about such solutions given their past history. Personally, I’m not in the “I’d rather die than live like this” mindset…yet, but I see the potential for 50% of the population turning that way, and it doesn’t take half by a long shot.

President Eisenhower wrote 1954 to his brother Edgar:

The H. L. Hunt types are still stupid, but their numbers are now legion.

The point to taxing the rich is not fairness. The point isn’t even to raise money. The point is to keep them from destroying the country. We did pretty well as a country when we had an explictly confiscatory top rate. IIRC the Founders favored heavy estate taxes to prevent the growth of a hereditary ruling class.

I worked for a billionaire for a two years in the late 90’s. This billionaire’s wife had an average Amex bill of $100K per month. Per. Month. I know because I had to wrangle the receipts so the accountant could balance the books.

They were worth approx $4 Billion. The husband was a nice guy. The wife was insanely jealous of the people who had more money. Peter Norton, of Norton Utilities fame, lived, literally, up the block. The wife was always complaining that Peter “had nicer things”, “got invited to better events”, “threw higher end parties”, “had nicer cars for their kids.” This is the same family that built a building so the daughter could get into Stanford, after which she flunked out.

It was amazing how, to this family, $4 billion wasn’t enough. They wanted more.

@EddieInCA:

That is an awesome story! Peter Norton as a billionaire is odd. Who’s heard of or has used Norton Utilities since ~1997. Apparently he got bought out hard back in the day.

And that your dude’s wife was super jealous. Why?

@EddieInCA:

It’s like The Great Gatsby with soccer moms.

@gVOR08:

Spot on! All democracies run on some flavor of capitalism, but, beyond a certain point, accumulation of riches undermines democracy. All countries require a military, but militaries by their very nature tend to foster among soldiers a greater allegiance to the army than to the country itself. Finally, democracies must allow the will of the people to be expressed, but that means that demagogues are constantly prowling along the edges.

A healthy democracy harnesses all these forces. Today, two of the three have grown dangerously unbalanced.

The pursuit of folly.

The very leviathan of government you all so ardently advocate provides the mechanisms for the very wealthy to manage their taxes through influencing Code. (Not to mention regulatory capture or subsidy) But who should be surprised? When the NY governor observes that 1 guy in 100 pays the taxes for 50, and when 10 pay for 67, what do you expect? Fair share? Bull. That’s not a progressive system, it’s larceny. So they are going to do something about it.

The US seems to have found a natural level of visible (read: income) taxation those really paying the freight will tolerate. It’s been steady for quite some time. You’ll be writing articles like this and gnashing teeth for the next 50 years, just like the last 50, until you come to grips with that. People aren’t leaving CA, NY, NJ, IL – blue states all – for no reason.

@Guarneri: Fifty or sixty years ago JFK lowered the top rate from around 90 to around 70. Since then it’s moved jerkily to 30 something. This is steady?

@Guarneri:

Guarneri interpreted:

Yep, we are all completely helpless to write tax law that forces the rich to pay. Give up now! The only way – the only way, people – is to stop that whole ‘government’ thing and let poor people die. I mean, unless you want the rich to have everything, we’re gonna have to cut off people’s health insurance. So sorry.

@gVOR08:

I know, and I thought Trump instituted the biggest and bestest tax cut ever. Apparently not, it’s all been stable.

@Guarneri:

You know I’m going to ask you the question, right? And then you’ll have to run away.

@de stijl:

The irony is that Peter Norton wasn’t worth as much as this family. He just had a nicer house, which drove the wife crazy. This was during the run up to the Tech Boom, so Peter Norton was a minor celebrity as we all remember.

@James Joyner:

Why do you think dead people need money?

No, seriously — think through that phrase “death tax”. The heirs didn’t die, so it isn’t a “death tax” for them. In fact, they aren’t being taxed at all, because the money was never theirs to begin with. What’s getting taxed is the estate of the dead person. Estates need money to pay off debts, and to decently bury the deceased, and so forth — but that’s about it. Taxing the dead seems like the most unobjectionable sort of tax imaginable. It’s also the easiest point in the process to identify exactly how much wealth is being transferred.

And if you don’t want to be taxed after you’re dead, you could always, you know, give the money away while you’re still alive. To your heirs, if that’s what you want. With the recipients paying appropriate taxes on those gifts.

@DrDaveT:

I never argued they did. What I did argue:

Let’s say the children are born when the parent is 30. That means one makes it to 50 with a super-rich parent to pave the wave for them through college, professional school, starting a business, etc. while the other gets cut off at 10.

Now, I suppose we could argue that the super-rich shouldn’t be allowed to pave the way for their kids even while they’re alive. There’s a meritocratic argument to be made there. But I don’t understand how one can think it’s fine when they’re alive but, the moment tragedy strikes, the kid should be left without the benefits.

Presumably, there are trusts and other avenues for avoiding the government confiscating that wealth. But I don’t see an argument for what they should be permissible but that we should punish the heirs of those who didn’t hire good enough accountants.

@James Joyner: @James Joyner:

You called it a “death tax”. I was giving you the benefit of the doubt, that you might possibly be using the phrase literally, rather than invoking a deliberately misleading propaganda phrase invented by defenders of wealth concentration to confuse the issues. In that guise, it’s a lot like using the phrase “right to life” (or perhaps even “baby killer”) in a discussion of abortion. I was frankly startled to see it in your reply.

So what do you mean when you say “death tax”?

Why have you abandoned the context of my original comment, which was about consumption taxes? Paving the way for your kids — buying them things, paying their tuition, setting up trust funds, etc. — are all acts of consumption, to which a consumption tax would apply. I was just closing a loophole. (And yes, setting up a trust fund should also be treated as consumption — you are making a transfer of assets out of your control. Most people don’t realize that the US doesn’t really tax income, it taxes transfers of assets.)

@Guarneri: “People aren’t leaving CA, NY, NJ, IL – blue states all – for no reason.”

For once we agree. In fact, I’ll go one step further — if we are speaking statistically and not anecdotally, people aren’t leaving blue states at all.

@Michael Reynolds: People like “Guraneri” believe the government depends on the consent of the governed only when it applies to rich people and taxes. Poor minority men who protest they are treated unequally by the police? Shoot them or jail them. Rich white guys who might not be able to afford that tenth yacht if they actually have to pay taxes like everyone else? Tremble before their wrath.

@James Joyner: “But I don’t see an argument for what they should be permissible but that we should punish the heirs of those who didn’t hire good enough accountants.”

Thanks to Trump and his followers, the inheritance tax now kicks in at ten million dollars or above. I suppose you could call it “punishment” to have to pay taxes on every dollar above ten million, but I’m really having a hard time finding a lot of sympathy in my heart for these poor dears.

There are people in this country with real problems. Having to buy a Cirrus Vision private jet instead of that Gulfstream really feels pretty far down on the list for me.

@wr: I’m not sure at what the level of estate taxes should kick in but concur that it’s now quite high. I was simply responding to the notion of “inheritance as an antisocial behavior.”

@Guarneri:

“People aren’t leaving CA, NY, NJ, IL – blue states all –

for no reason.”Thought I’d fix your sentence for you. Consider it a courtesy.

@Michael Reynolds: That’s strange. My translator gave: “I’m unwilling to pay the kind of taxes that will preserve programs that I don’t imagine ever needing, nor are other people that I know in my socioeconomic class, so we’ve cobbled together this fiction of a government that is choking the life out of us and hope you won’t see through it.”

One of our programs must be misaligned, or maybe this is postmodernism at work. Who can tell?

@James Joyner: Either James or someone else is going to need to explain to me how estate tax works that means that if your parents die rich when you are 10 makes the settlement of the estate different than if they die when you are 40. I do get that the 10 year old kids have to have a trustee for the wealth, but I’m not sure how that makes a difference. Do trustees routinely embezzle from the estate with the law turning a blind eye? Are rich people routinely so stupid that they don’t imagine that they can die young so that they die intestate? I’m just an ignint cracker, so I’m not following this “get screwed twice” argument. Somebody hep me out heah. I just represented an estate a few years ago.

@Just nutha ignint cracker: I think the idea is that the 40 year old gets to live off their parents’ wealth through the college & young adult years and into middle age, until their parents die and the government swoops in and confiscates every last farthing. The 10 year old is losing twice because they not only lose their parents, but lose out on the 30 years of living off their parents’ wealth before the government confiscation. They’ll be left to live off of nothing but Social Security Survivor Benefits, and we all know how that turns out *cough* paul ryan *cough*.

@Han:

Of course, under current law it’s actually only 2/5 of the farthings, and the first 4.56 billion of them don’t get taxed at all…