The Emerging Democratic Majority at 20

How well has the famous thesis fared?

NYT chief political analyst Nate Cohn reflects on what he terms “The Lost Hope of a Lasting Majority.”

Today we wish a belated and maybe not-so-Happy 20th Birthday to “The Emerging Democratic Majority,” the book that famously argued Democrats would gain an enduring advantage in a multiracial, postindustrial America.

There are countless explanations for the rise of Donald Trump and the growing dysfunction of American political life. This book does not necessarily rank at the top of that list. But when historians look back on this era, the book’s effect on American politics might be worth a mention.

The thesis that Democrats were on the cusp of a lasting advantage in national politics helped shape the hopes, fears and, ultimately, the conduct of the two major parties — especially once the Obama presidency appeared to confirm the book’s prophecy.

It transformed modest Democratic wins into harbingers of perpetual liberal rule. It fueled conservative anxiety about America’s growing racial diversity, even as it encouraged the Republican establishment to reach out to Hispanic voters and pursue immigration reform. The increasingly popular notion that “demographics are destiny” made it easier for the progressive base to argue against moderation and in favor of mobilizing a new coalition of young and nonwhite voters. All of this helped set the stage for the rise of Mr. Trump.

The book’s thesis already looked shaky by 2004, when George W. Bush, who had lost the popular vote in 2000, won re-election. Still, even though he won the popular vote by a mere 2.5%, the contest again hinged on a single state—this time Ohio rather than Florida, which he won by only 2.1%. Since then, Democrats have won the popular vote in every single presidential contest. Indeed, 2004 is the only Republican popular vote win since 1988. Surely, that seems like a Democratic majority has emerged.

I do think Cohn is right, though, that Democratic and Republican elites took different messages from the thesis. The former took the bumper sticker version of the message, completely ignoring the nuance, and saw a license to abandon the Clintonian triangulation strategy and run on an increasingly progressive platform. The latter saw a need to double down on stoking fear among the declining white plurality—and, frankly, cheat by suppressing the votes of minorities likely to be in the opposition column.

Regardless, he admits that the book’s thesis has been straw-manned:

This is a lot to attribute to a single book, especially since the book does not really resemble the Obama-era caricature advanced by its supporters. The book does not put forward what became a commonly held view that racial demographic shifts would allow Democrats to win through mobilization, a more leftist politics or without the support of white working-class voters.

Instead, the book argued — not persuasively, as we’ll see — that Democrats could build a majority with a (still ill-defined) “centrist” politics of the Clinton-Gore variety, so long as they got “close to an even split” of white working-class voters.

“We were clearly overly optimistic about that prospect, to say the least,” said John Judis, one of the authors of the book, of the prospect of such high levels of Democratic support.

But, again, the party didn’t follow their prescription. The era of big government, it turned out, was not at all over.

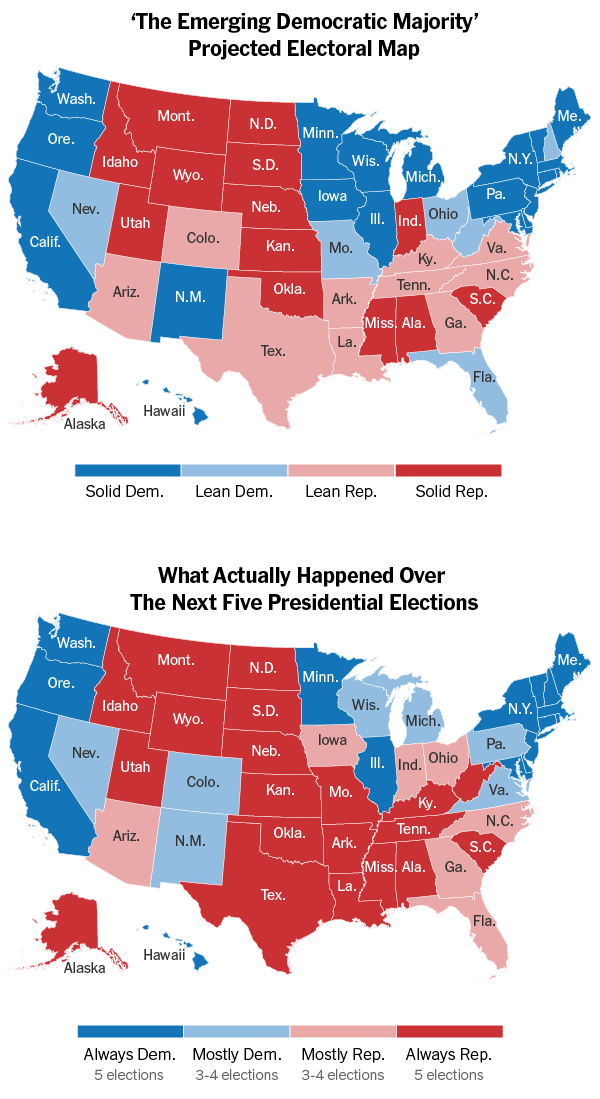

Regardless, Cohn contrasts the map projected by Judis and Texeira with what has actually transpired:

What should you notice about the map of the projections?

First, the book is very cautious about predicting any Democratic gains attributable to racial demographic shifts. There’s no blue Georgia, no blue Texas, no blue North Carolina and no blue Arizona. There’s not even a blue Colorado or blue Virginia, which really did come to pass just six years after the book’s publication. Only Nevada and Florida — already highly competitive battlegrounds in 2000 — could be characterized as flipping to the Democrats because of the growing diversity of the population.

Second, the map illustrates that the authors supposed extraordinary levels of Democratic support among white voters without a college degree. Not only are white working-class battlegrounds like Iowa, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania characterized as “solid Democratic,” but Republican-leaning states like Ohio, Missouri and even West Virginia are characterized as “leaning Democratic.”

So, again, the authors made Democrats holding roughly half of blue-collar whites a baseline condition for their thesis to be true. That didn’t happen.

Cohn argues that they should have seen it coming:

The characterization of West Virginia as “leaning Democratic” — despite George W. Bush’s victory before the book’s publication — is a telling indication of the problems underlying the book’s thesis.

While the book correctly anticipated Democratic strength in postindustrial metropolitan areas, it failed to appreciate the challenge of holding on to blue-collar white voters at the same time.

The authors said the “key” for Democrats would be in “discovering a strategy that retains support among the white working class, but also builds support among college-educated professionals and others.” But the book did not contain a road map to pulling it off. It said, “They can do both.” The optimism was rooted in the assumption that Clinton-Gore had already solved the problem.

The authors dismiss the Bush victory in 2000, arguing that Al Gore failed “largely because of factors that had nothing to do with the appeal of his politics.”

While the book acknowledged that Mr. Bush was assisted by Mr. Gore’s stances on the environment, coal, abortion and gun control in white working-class areas, it didn’t appear to take these cultural issues as a serious problem for Democrats. At the very least, they weren’t considered serious enough to move West Virginia out of the Democratic column.

Instead, the authors advanced the argument that the strong economy in 2000 was actually part of Mr. Gore’s problem, by allowing working-class whites to vote on cultural issues rather than their economic interest. The Clinton sex scandals were also considered a necessary condition for Republican strength; without Bill Clinton dragging them down, Democrats would rebound. Whatever the merits of these arguments, it isn’t especially credible to argue that the 2000 election — held at a time of peace and prosperity — was anything like a worst-case scenario for Democrats.

Even as one who voted for Bush, I agree with their analysis of that election. Further, it bears repeating: the Democrat won a plurality of votes in that contest despite these obstacles.

In retrospect, gun control and environmental issues were harbingers of one of the major themes of postindustrial politics: White working-class voters were slowly repelled by the policy demands of the secular, diverse, postindustrial voters who were supposed to power a new Democratic majority.

The book is all but silent on the issues that fit into this category, like same-sex marriage, immigration, climate change, inequality or racial justice. In fairness, the book was written before many of these issues rose to prominence. It was written near the “end of history.” The 2000 election campaign was a relatively dull affair, with low turnout and few stark differences between the candidates. No one could have foreseen the next 20 years of wars, economic crisis, cultural change and social unrest.

Well, no. Clinton directly appealed to these voters on many of those issues. Working with Newt Gingrich and the Republicans, he “ended welfare as we know it” and signed the Defense of Marriage Act. The courts and the party’s increasingly urban, educated base pushed the leadership left on these issues.

Yet despite all the intervening events of the last two decades, the book did get something very important right: America was entering a new era of postindustrial politics.

As Mr. Judis noted in an email, professionals have “grown, if anything, more Democratic” than the book foresaw. Maybe the book didn’t predict a blue Virginia or a blue Colorado — but in some sense, those shifts proved that the thesis of the book was more powerful than its authors imagined. The industrial era of political conflict really was coming to a close.

While the authors argued Democrats would follow in the footsteps of Progressive Era Republicans, who won overwhelming electoral victories, the next 20 years proved more reminiscent of the Gilded Age — the decades of political division, resurgent populism, political reaction and growing inequality that ultimately set the stage for the rise of the progressives.

Perhaps this is the book’s greatest shortcoming. It assumed that the transition to a new postindustrial, multiracial society would come without anything like the conflict, unrest and reaction that accompanied industrialization. Indeed, the book failed to imagine the basic contours of political conflict in the postindustrial era — let alone why the Democrats would be well positioned to guide the nation through those challenges. Instead, it assumed a peaceful, prosperous and content nation, one where centrist Democrats offering small solutions to small problems might fend off stolid Reagan-era Republicans in perpetuity.

That’s fair. But it also missed something more fundamental that Steven Taylor and I have been harping on for a long time now: we’re not a majoritarian political system.

Even though Democrats have won the popular vote in seven of the last eight elections (and arguably would have won eight straight had Bush not been the minority-winner incumbent in the first post-9/11 election), Republicans have won the White House three times during that span. Further, because the party is vastly over-represented in the Senate, given that each state gets two Senators regardless of population, they have managed to pack the Supreme Court with Federalist Society Justices, thus thwarting the agenda of Democratic Presidents.

So, even though a Democratic majority has “emerged,” it doesn’t necessarily translate into Democratic governance.

Cohn continues:

The theory that demographics are destiny is a tempting one. In a certain sense, the last 20 years have vindicated it. If you want to guess how a state or county has shifted over the last two decades, demographics can tell you just about everything you need to know. If you want to build an election needle or weight a political poll, demographic data is awfully useful, too.

Yet demographic change rarely offers a path to political dominance, at least nowadays. Demographic shifts are transforming the United States — but at a glacial pace. Over a four-year period, Democrats might gain a mere half percentage point because of the increased nonwhite share of the electorate — assuming everything else is held constant. A half-point is something, but it’s easily swamped by other factors, like a shift in the economy, a different slate of candidates, a midterm, or just a few too many years in power.

Sure. Further, my longstanding critique of the thesis is the assumption that Hispanics, or even Blacks, will always vote the same way. While Republicans have seemingly gone out of their way to alienate both groups (so much so that they turned once-rock solid Red California into a reliable Blue state) we’ve seen a slight shift of both groups, particularly men, to the GOP.

In the real world, things aren’t held constant. Demographic change can provoke backlash. And, even if it doesn’t, a party courting new voters might still find itself losing ground among its old supporters, who were brought to the party by a different set of messages, issues and candidates. And even if a party does everything right, and manages to squeeze a point or two out of demographic shifts in a given election — the way President Obama probably did in 2012 — it might just tempt a party to cash in its electoral chips on an agenda that costs support from a key group. It might even convince a party that demographics are destiny — and that the hard work of persuading voters and building a broad and sometimes fractious coalition just isn’t necessary.

Political parties evolve over time and their coalitions evolve, too. The Republicans like to brand themselves the Party of Lincoln, their first winning Presidential candidate, but they’re obviously not that party anymore—1860 was a long time ago, after all, and the issues have changed. Democrats still see themselves as successors to FDR and, in many ways, they still are. But they’ve slowly hemorrhaged their once near-automatic support from the South over civil rights and other cultural issues.

Further, I don’t see any “demographics is destiny” thinking at the level of national campaigns. If anything, we’ve shifted away from a politics of persuasion and moved to a politics of turnout.

The notion that college-educated voters would have common cause with working people is just ignorance of basic human behavior. The college-educated did not spend four years studying in order to be equal to the guy nailing up sheet rock. College-educated folks are almost always completely divorced from the blue collar world* and wouldn’t have it any other way. With education comes snobbery, condescension and contempt for the degreeless.

99% of kidlit writers have a degree. I’m the 1%. The reaction when I tell other writers I’m a drop-out with a GED? Blank confusion. It’s like an old Star Trek when they’d ask a computer the meaning of life or whatever and sparks would start shooting out. Successful. . . no education. . . 150 books . . .this cannot be. . . does not c-c-c-compute. Cue shower of sparks.

A degree in our society ennobles. You’re no longer a peasant, you’re educated, you’re special. Anyone who understood human behavior would have seen it coming and known intuitively that there would be very little unity across the educational divide.

*Of the regulars here, who lacks a college education? Ozark and Cracker, maybe? Of those with degrees, how many of you have worked a blue collar job for more than a summer? DeStijl and. . .?

As I believe I read chez Kevin Drum but perhaps somewhere else, the approach of Activism rather than the approach of Organisers (the example of Trade Union organisers was used as my memory goes.

This seems very accurate (and one can see if among your Lefty commentariat here).

And a gross political error and act of self-harm given your electoral political structures, insofar as the evidence rather shows that mobilisation for the Democrats is too shallow a pool in too many key electoral geographies (and not usefully deep or wasted depth in too many others).

Of course partially legitimate excuses on suppression and barriers can be advanced, but that is rather self-defeating, like whinging on about the enemy using unfair tactics (yes, but whinging doesn’t change the results).

While dreaming academicaly of structural revisions is fine, if you are to really stop what can indeed be called a kind of new fascism, pragmatic focus on how to Convert some percentage of the while and even hispanic working class in middle geographies and maybe south-western is ndeeded. And rather obviously artch and pious insistance on pursuit of cultural transomration politics is not a path to success there. As on battlefield, dramatically asserting Hill 99 Must Be Taken/Held doesn’t make it possible, and relying on moral élan to drive for a bridge too far will just open up the potential for a win by the new fascism, which evidently is a worse outcome than pausing….

Democrats have made mistakes. Democrats have missed opportunities. But Cohn tells basically a Murc’s Law version of this story, in which Republicans play little role, just passively benefitting from developments. Judis and Texeira failed to anticipate how hard Republicans would work to create and exploit a culture war. Republicans succeeded in creating a tribal identity to which voters are loyal. For a number of reasons, mostly not trying, Dems haven’t generated a similar identity.

I guess I don’t understand the basic thesis. Clinton-era Democrats failed to pass health care reform, lost control of Congress in a historic shift, then capitulated to Republicans on welfare reform and DOMA, and then lost an election in the EC and then capitulated/went all in on Iraq and the War on Terror, and then actually lost a presidential election.

Why would anyone cling to these strategies? What’s the logic here? Is appeasing older white people more important than failure? I guess the answer is yes.

@Modulo Myself:

Voila, the illustration of the problem you have. The Activist mindset. Framing as appeasing…

Morally appropriate failure rather better than morally impure success.

Given that 60% of the population – and an even higher percentage of voters – are White, while Blacks are 12% and Hispanics maybe 18%, yes, we should look for White votes.

@Lounsbury:

Clearly you don’t know about, ‘manifesting.’ In which you wish real hard and then it happens.

I manifest the disappearance of the telephone pole in my back yard. It’s still there, but it’s only a matter of time.

@Michael Reynolds: Well…Jim Brown32. Lets see: Fast food restaurant custodian/dishwaher, pizza cook, fast food cook, truck unloader, warehouse stocker, pool digger, etc.

Not to mention that I grew up in a military family that needed foodstamps and WIC to make ends meet. Joining the military as late as I did, I brought a lot of social experience to bear that my peers didn’t have. Hence, I often received notes and email from my troops (white, black, and hispanics) that I was the most relatable officer they’d ever served with. I’d worked with people like their parents in my time goofing off after highschool and in between college “sabbaticals”.

Most people are looking for status and affiliation–it is a fundamental human yearning. We will place social value on almost anything that gives us advantage in the status and affiliation game. This is a high stakes game–no question. Status and affiliation offer social mobility and maneuverability for people to achieve their goals. What I’d do when I integrated the waterfront white wonderland in panhandle Desantistan? I fly the armed forces Service flags right in my front yards. Why? Cause even though Jim Brown is a N1&&3r to these people–Im affiliated with something they hold in the upmost respect. It gives me some social cover with the neighbors and the police that patrol the neighborhood. I don’t have any military symbols at my home in Central Florida–don’t need it. Other affiliations are more useful in that area of Florida

Where most people go off the rails is status become inseparable from their personal identity.

Jim Brown views status merely as a tool to–there are times when status enables social access to groups and times when it hinders access. I am no respecter of persons so if you’re a good dude or dudette–Jim Brown doesn’t give 2 shits about your social status. I grill out occasionally with the homeless guys my maintenance man hires to help him around my DeSantistan home. Sometimes I put em up in the basement if the weather sucks. Most of em are good folks but with serious problems that impact their ability to join regular society. And even though socially, they are nothing compared to me, in that moment–I view it as a few dudes drinking a beer and eating burgers in the driveway. No more no less. Not service. Not giving back. Its savoring the full spectrum of the human social strata.

There is a lot of beauty in this world for those with the boldness to explore and embrace variety.

@Lounsbury:

Democrats have won the popular vote in every presidential election since one in the past 30 years, have pried college educated white voters away from Republicans, still receive ~90-95% of the black vote, win a supermajority of youth and queer voters, reduced Republican Latino voter share from ~45% in the 2004 election to the mid to low 30s now, control the White House and Senate and House, have just won a statewide abortion referendum in red Kansas, and have outperformed in every special election held this summer, including winning House races polls said they would lose in Alaska in upstate, rural New York.

But because elements of are system are undemocratic and anti-majoritarian, Democrats are ‘failing.’ Pray tell, what are Republicans doing?

The establishment meltdown when Democrats hold the House and the Senate this November is going to be epic.

And that is all propaganda. A college-credential does not equate to being educated, in the real sense of discipline of intellect, regulation of emotions, establishment of principles. There was a time when having gone to college increased your chances of becoming educated if you kept up the disciplined thinking and remained curious. But a college-degree is a status good, with the ultimate being a degree from one of the status universities, e.g., Harvard, etc.

Unfortunately, the incentive of schooling is to get good grades, not real learning. Parents, teachers, colleges all want good grades and care little about retention after the test. But this stratification in school promotes the idea that getting poor grades somehow makes you lesser than the conformists. And the “good students” learn to conform and not think lest the get the wrong answer. The gullibility of the “educated strata” in contrast to the working class was remarked on by Ludwig von Mises and C.S. Lewis.

It should be noted that college is now majority for women at a 60/40 split these days increasing since 1980. Some might try to say this means men are just too dumb for college, but the St. Louis Fed sees it as opportunity differences.

@JKB:

“Why can’t we have both?”

@JKB: if the only jobs open to me as a woman with a high school education are badly-paid cleaning and caretaking jobs, you can bet your buns that I’m going to go like a laser beam towards a college degree that cracks the glass ceiling and allows me to get a decent salary.

There’s also a similar sorting mechanism among the majors, I noticed. Women who made the jump over into STEM majors either went for the higher-paying ones or knew that they were drawn to the really theoretical ones like mathematics. One reason why there were so few women in physics when I was in university–too applied for the math-lovers and at the same time too theoretical for the engineers.

@Michael Reynolds: Well, I grew up working on a farm and now have an MFA. Five of my siblings have community college degrees and are still blue collar yet liberal. Among my two dozen nieces and nephews, almost all have four-year degrees, and several have advanced degrees. Yet oddly, the more advanced ones are nearly all right-wingers. I think the PhD nephew is still a climate change denier. You might consider it’s just the specialized educated circles you travel in that are condescending, and there might be reasons other than education makes you so.

@Jim Brown 32:

Those are serious blue collar, dues-paying jobs. Respect.

Humans do tend to be hierarchical. Back when I was writing restaurant reviews I had to decide whether I could or should give 4 stars (all the stars I had) to a humble BBQ joint, or whether 4 stars was only for fine dining. I decided that it was about being great at what you set out to do. If you set out to do fine dining, you gotta deliver. It didn’t matter to me whether you were CIA (Culinary, not Central) and were a sous chef for Charlie Trotter, the only thing that mattered was what you produced, what you did. If you set out to smoke barbecue and your brisket is moist and tender and the meat falls off the ribs, hell yes, you can get 4 stars.

I have more respect for a great carpenter than I do for a mediocre film director. Don’t tell me who you are, tell me what you do. I suspect a lot of people would agree with that sentiment in theory, but still go weak in the knees over a title or a position or a degree of celebrity. (Side note to Americans: we famously don’t believe in royalty. Right?)

Incidentally, I destroyed that BBQ joint with my 4 star review. Lines out the door and only so many smokers. They lasted less than a year before exhaustion set in. Unintended consequences.

Just ran into this by Joel Kotkin ‘The revenge of the material economy’ at Spiked. It will inform the Democrat loss of working class voters I believe.

@JKB: While it’s true that the working class has demanded a bigger share in the post-pandemic economy the railroad strike is a weird example. They got very little out of the bargain.

@Michael Reynolds:

Won’t speak for Ozark, but for me, BA, +90 credits gaining a teaching certificate, + MA in a field outside my original undergrad degree, + a basket of 103 assorted additional university credits (mostly in the highly discredited, useless, ivory tower, pointy-headed liberal arts). I would have thought that my never-ending stories about life at the colleges I’ve taught at would have been a clue, but I guess not. 🙁

@Just nutha ignint cracker: And for the record while I’m here, I stayed in blue collar work after graduation for the money. College degrees were already becoming a drag on the market when I graduated in 1975 (my dad had predicted and warned me of that in 1969 when I was still in high school) and the irresistible lure of making more working part time than the head of the instrumental music division at my college made working full time* was too much for a person with limited opportunities to resist (it was the peak of stagflation, most of us went to grad school to postpone unemployment).

*That fact drove Dr. Layer to leave the ivy-covered halls of Seattle Pacific University for a position as Director of Music programs for Mercer Island school district a few years later. (And I still made more than he did. 🙁 )

@Lounsbury: While I see, and even agree to some limited sense with, your point, I’m not of a mind to call DOMA and welfare reform “morally impure success[es]” or even successes at all. Compromising by getting nothing of what you wanted is only compromise in the minds the owners of capital and their greed-headed rightie minions.

@DK: “Why can’t we have both?”

Because, at least according to some among our commentariat, wanting both is embracing morally pure failure instead of embracing morally impure success. For the rightie greed-heads, the message is “stay in your place and stop wanting what I have.” Be it housing, adequate diet, livable wages, right to vote, you have to take whatever your betters will give you and call that “winning.” The investment guru says so and calls out the lefties as too idealistic, so it must be true.

@JKB:

So, the working class should unionize and strike to get more?

Strong agree.

@James Joyner: I will admit to not following it that closely, but I thought they got the ability to take unpaid sick days with fewer penalties, and the can has been kicked down the road to after the midterms.

Is my vague understanding wrong?

@Michael Reynolds: Can we just all accept that most kidlit writers are terrible human beings and stop trying to claim that the way they treat MR defines the way all classes Michael doesn’t like to day treat classes Michael does like today? I think it would save us a lot of time around here.

@Michael Reynolds: “Of the regulars here, who lacks a college education? Ozark and Cracker, maybe?”

Which is why the other regulars around here treat them with such condescension and snobbery Point proved!

@Lounsbury: “Morally appropriate failure rather better than morally impure success.”

Well, yes. Because if the Democrats manage to win power and then use it only to enact a Republican agenda, then it’s not better than having actual Republicans in power. Unless you happen to be one of the insiders who gets money tossed to him by one team or the other, the only reason for choosing a party is what they stand for.

I know, so naive.

@JKB: So you’re a union man now?

@wr: a perfect path to the successful resurgence of fascism, a perfect replication of the pious perfectionism of the 1930s Left, collapsing Centrism and even moderate Right into Fascism with no difference. That impoverished black-and-white thinking worked so very well last round (as if one did not see with Trump himself how utterly fallacious the “no difference’ between centrist and neo-fascists is relative to real world results, mitigated only by Trump’s sheer incompetence.)

@Michael Reynolds: “Humans do tend to be hierarchical.” Human beings are in the end nothing more than suped-up chimpanzees. And apes are hierarchical. Beni adam, Beni adam – we are what we are and rather than engaging in arch abstractions as wisful thinking, work with us as we are to mediate. For the hard Left however they have not really dropped Soviet New Man kind of thinking

@DK: “Democrats have won the popular vote in every presidential election since one in the past 30 years”

Your vote is not a Popular Vote so that is, well, self-deception – as I noted in my comment, over-achievment in majority Dem areas is rather bloody pointless.

Where you are failing is addressing the reality of the the electoral structure (other than excuse making, which while true on the margins does not change a reality). That electoral structure, two hundred odd years old is what it is, and you need to address the Geographic Specific Failings.

Not bloody prattle on about winning national votes.

The electoral structure overweights regions, and to effect change barring bloody civil war, you need to stop the excuse making whinging on, and address by stemming the losses and turning around rural to reconsolidate.

Or you lot can continue to whinge on and make excuses, that yes, have foundation but change not one whit the end result. (but you don’t really want to, not your fraction, you rather prefer morally pure failure and performative posturing, to dirty pragmatism)