The History of Blackface

A reading recommendation.

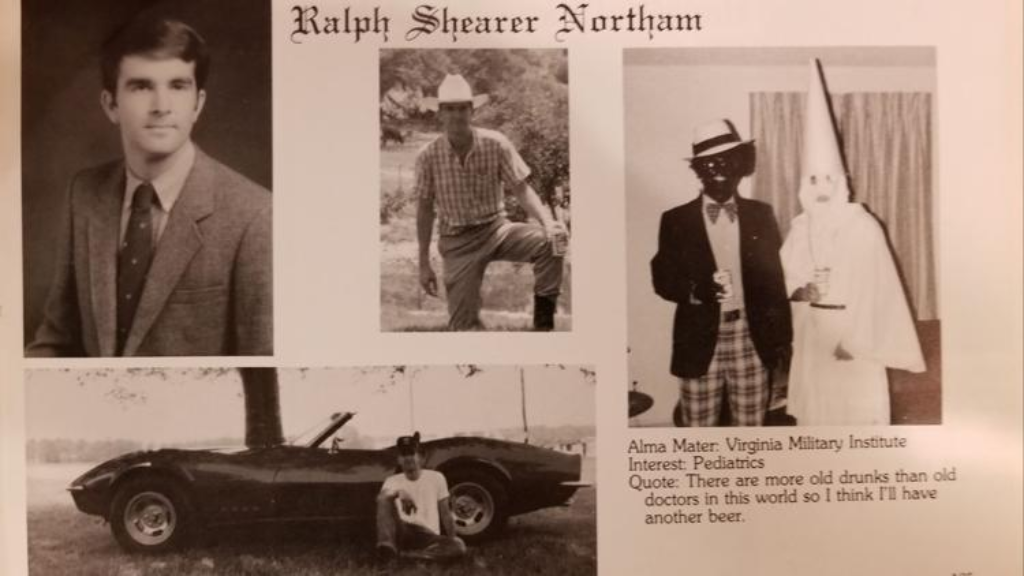

I would highly recommend the following essay by Rhae Lynn Barnes (assistant professor of American cultural history at Princeton University): The troubling history behind Ralph Northam’s blackface Klan photo.

I would highly recommend the following essay by Rhae Lynn Barnes (assistant professor of American cultural history at Princeton University): The troubling history behind Ralph Northam’s blackface Klan photo.

I spent a decade poring over blackface composites from yearbooks and fraternal orders, watching cracked film footage and cataloguing more than 10,000 blackface plays at Harvard University. Those plays and Northam’s racist photo show us the centrality of amateur blackface minstrelsy to American cultural life and universities. They show how upwardly mobile white men concentrated white-supremacist political power in the century after the Civil War, using the profits of amateur blackface to build white-only institutions and using blackface performances to articulate to voters their legislative commitment to white supremacy.

They also show how persistent those power structures remain.

Though blackface was the No. 1 entertainment form throughout the United States in the 19th century, it has a particularly notable legacy in Virginia. The first globally famous minstrel troupe hailing from New York City rebranded itself as the Virginia Minstrels in 1843. Dan Emmett, the group’s founder, understood his minstrel troupe needed to project a sense of authentic, stereotypical blackness. Virginia, a state that imported enslaved Africans as a colony as early as 1619, embodied the complex relationship between blackface entertainment, slavery and American culture in a single word. The troupe did not just borrow Virginia’s brand, but shaped it: Its song “Dixie” became the unofficial Confederate anthem.

[…]

The era we now call Jim Crow America was named after a famous blackface minstrel character. His signature debut song “Jumpin’ Jim Crow” reached global fame in 1832, but it wasn’t until the 1860s that everyday Americans bought commercially packaged how-to minstrel blackface plays to perfect these racial stereotypes. A new era of segregation, mass culture and blackface emerged, where blackface-imitating pro-Klan movies such as “Birth of a Nation” were the go-to entertainment form for young men.

The whole thing is worth a read.

One part that did strike me was this:

Blackface was a fundraising and socialization tool for white, all-male, Christian civic organizations such as the Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks.

[..]

As late as Gerald Ford’s administration in 1974, the annual Charlottesville Lions Club Minstrel show was still so popular it was recommended in travel guidebooks.

It took me a second to connect the dots on local civic organizations (Elks, the Lions Club) and fundraising and then I remembered the Lion’s Club Follies in Temple, Texas when I was a kid. I did a quick Google search and found a story in the local paper from 2015 about the show’s 76th edition, which included this line in passing: “The show traces its beginning to 1936, when it was a minstrel show which evolved into the variety show it is today.” I remember attending the Follies when I was in probably third grade, although I don’t recall any of the skits, nor am I suggesting that the show was problematic at the time (but then again, I really don’t remember the specifics). But the history in the essay did help re-contextualize that type of event and how blackfaced white community leaders could use that type of racist “entertainment” to raise money in a seemingly harmless way, while really promoting white supremacy. It is both banal and insidious at the same time.

Again, I recommend the full piece.

I play banjo, and I’ve learned a bit about its history.

It’s an African instrument, recreated in the US by the slaves (I’m assuming they weren’t allowed to bring their instruments with them), industrialized with steel strings and frets, and then appropriated into the minstrel tradition, whereupon no black person touched a banjo for the next hundred years until the Carolina Chocolate Drops came onto the scene in the 20oos.

The banjo’s association with blackface minstrel shows was so bad that it the movie Deliverance really was a PR coup for the instrument. Being associated with man on man rape from inbred hillbillies was an improvement.

Anyway, that’s how offensive blackface is — it caused black people to abandon a part of their cultural heritage after it was appropriated by blackface.

Some very old songs like “Blue Tailed Fly (Jimmy Crack Corn)” are about slaves rejoicing the misfortunes of their masters. They are mostly eclipsed by songs about how them poor n-clangs miss slavery, like “Old Kentucky Home”. “O’ Susannah” was originally written in offensive n-clang dialect, and had verses about the deaths of hundreds of black folks.

Oddly, the banjo was then welcomed wholeheartedly into Irish folk music, and completely incorporated and adopted without a hint of blackface.

Not really odd. Most of the interior south was originally colonized by “Scotts-Irish”. Country music (note I mean actual southern folk music, not modern country rock and pop) is a Galapagos archipelago-style evolutionary mutant of Celtic folk music.

It’s not surprising then that stuff from country would be easily assimilated back into Irish music.

@Gustopher:

I envy you. I play (bad) fiddle and a bit of mandolin, but I’d love to play the banjo.

The best theatrical experience I ever had was the legendary show “Banjo Dancing”, a 1-man show by Stephen Wade at Washington DC’s Arena Stage. It ran for a decade; I saw it 5 times.

@Gustopher:

That blackface minstrel shows were offensive to black people I have no doubt. There’s a famous quote from Frederick Douglass to that effect. However this

is not true. There are many extant 19th century photos of black minstrel companies, i.e. minstrel companies with African American casts, and black jazz bands from the 1920s playing banjos. Oddly, the black minstrel companies frequently performed in blackface.