Trump, Nationalism, And The Lessons Of World War One

One hundred years after the end of World War One, the forces that led to it are waking up from a long slumber.

Today marks the end of World War One, which also went on to be called “The Great War,” and, somewhat ironically given the fact that Europe erupted in conflict just twenty years later, the “War To End All Wars.” To mark the occasion, French President Emmanuel Macron invited the leaders of nearly 100 nations to mark the occasion, and he used the occasion to push back against the passions that made that war inevitable and which now threaten to revive themselves today:

PARIS — In the shadow of a grand war memorial here, French President Emmanuel Macron marked the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I by delivering a forceful rebuke against rising nationalism, calling it a “betrayal of patriotism” and warning against “old demons coming back to wreak chaos and death.”

Macron’s speech in French to more than 60 global leaders, including President Trump, aimed to draw a clear line between his belief that a global order based on liberal values is worth defending and those who have sought to disrupt that system.

Those millions of soldiers who died in the Great War fought to defend the “universal values” of France, Macron said, and to reject the “selfishness of nations only looking after their own interests. Because patriotism is exactly the opposite of nationalism.”

His words during a solemn Armistice Day ceremony under overcast, drizzly skies at the foot of the Arc de Triomphe in the heart of this French capital were intended for a global audience but also represented a pointed rebuke to Trump, Russian President Vladimir Putin and others in the audience.

Macron has attempted to stand as a vocal counterweight to Trump, who recently called himself a “nationalist” and has moved to set the United States apart from global treaties, including the Iran nuclear deal, the Paris climate accord and a U.N. program for refugees.

Amid growing divisions in Europe that have strained the European Union, Macron defended that institution, along with the U.N., and declared that the “spirit of cooperation” has “defended the common good of the world.”

He denounced rising ideologies that have warped religious beliefs and set loose extremist forces on a “sinister course once again that could undermine the legacy of peace we thought we had forever sealed.”

The powerful remarks came as the world leaders gathered here have sought to mark the 100 years since the war by honoring those who served and died.

Ahead of the ceremony, dozens of world leaders dressed in black strode shoulder-to-shoulder along the Champs Elysees toward the Arc. Military jets streaked overhead, emitting red, white and blue smoke, the colors of France.

Yet Trump and Putin did not participate in the processions. The group, which had first gathered at the Elysee Palace, had come to the Arc on tour buses along the 230-foot wide boulevard. Bells at Notre Dame cathedral tolled at 11 a.m., marking the signing of the armistice of a war in which 10 million military troops perished.

But Trump and Putin took their own motorcades to the event and made separate entrances a few minutes after the main group. A White House spokeswoman said Trump arrived separately due to “security protocols,” though she did not elaborate.

(…)

The relationship between Trump and Macron has soured as the U.S. president has promoted an “America First” foreign policy that has unsettled allies on trade and defense. Macron has sought to counter some of Trump’s agenda and he has organized a three-day Peace Forum that will begin Sunday afternoon, just as Trump heads home to Washington on Air Force One.

In his remarks, Macron warned of the spread of falsehoods that fuel extremism and he encouraged the pursuit of science and art.

“The worst can be overcome as long as we have men and women of good will to guide us,” Macron said. “Without shame, let us be the men and women of good will.”

More from The New York Times:

PARIS — President Trump’s brand of “America First” nationalism was repudiated on Sunday as leaders from around the globe gathered to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the armistice that ended World War I and reaffirm the international bonds that have once again come under strain.

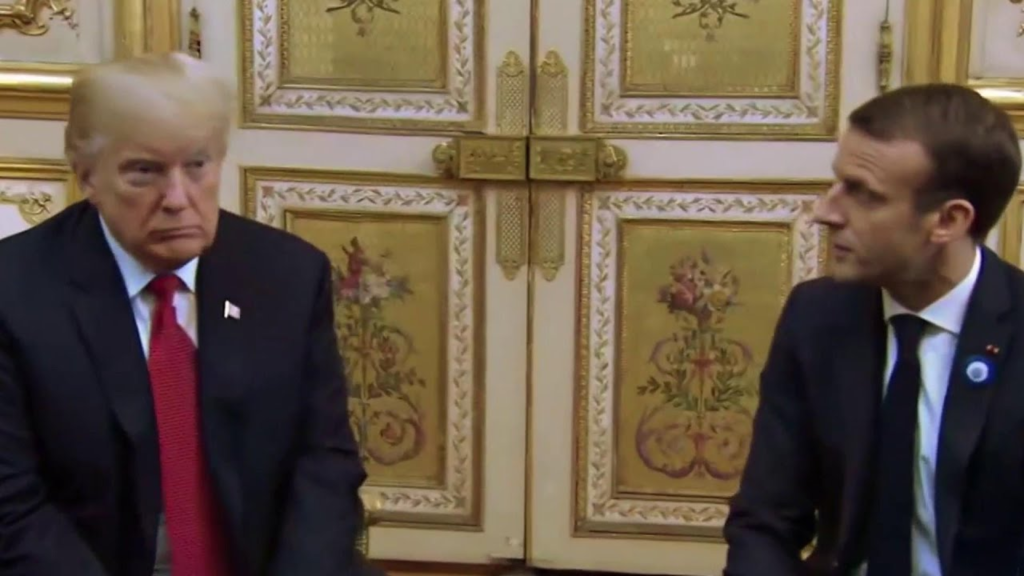

Stone-faced and unmoved, the American leader listened as President Emmanuel Macron of France used the ceremony at the Arc de Triomphe to denounce self-interested nationalism and extol the sort of globalism and international institutions that Mr. Trump has spent the last two years pulling the United States away from.

“Patriotism is the exact opposite of nationalism,” Mr. Macron said in a speech on a dreary, rain-soaked day. “Nationalism is a betrayal of patriotism by saying, ‘our interest first, who cares about the others?’ ”

Remembering the forces that led to World War I, Mr. Macron warned that “the old demons” have been resurfacing and declared that “giving into the fascination for withdrawal, isolationism, violence and domination would be a grave error that future generations would very rightly make us responsible for.”

Mr. Trump, who recently declared himself “a nationalist,” appeared grim as he listened to a translation of the speech through an earpiece and clapped only tepidly afterward. He had no speaking role at the ceremony and made no mention of the issues Mr. Macron raised during an address later in the day at a cemetery for American soldiers killed in the war.

The anniversary ceremony encapsulated the tension in the international arena as Mr. Trump seeks to rewrite the rules that have governed the world in recent decades. Mr. Trump has argued other nations have taken advantage of the United States, whether in economics or security, and that it was time to look after American interests first.

He has abandoned a number of international agreements on trade, nuclear proliferation and climate change, and disparaged alliances like NATO and the European Union. He has denounced virtually every trade pact that the United States has ever agreed to and recently forced Canada and Mexico to revise the North American Free Trade Agreement in a way that he says will benefit the United States more.

On the campaign trail last month, Mr. Trump railed against what he called the “rule of corrupt, power-hungry globalists,” as he put it during a rally in Houston. “You know what a globalist is, right? You know what a globalist is? A globalist is a person that wants the globe to do well, frankly, not caring about our country so much. And you know what? We can’t have that.”

The discord was on display during the president’s meeting with Mr. Macron on Saturday, a day after Mr. Trump issued a Twitter blast at his French host, calling a proposal for a European army “very insulting.” Mr. Macron explained that the idea was not to counter the United States but to relieve it of some of the burden for European security, a constant theme of Mr. Trump’s.

“We know where we disagree, and we are very straightforward in that — on climate, on trade, on multilateralism — but we work very well together because we have very regular and direct discussions,” Mr. Macron said later in an interview with Fareed Zakaria of CNN. Mr. Macron termed himself “a patriot” as distinct from a “nationalist.”

“I do defend my country. I do believe that we have a strong identity,” Mr. Macron said. “But I’m a strong believer in cooperation between the different peoples, and I’m a strong believer of the fact that this cooperation is good for everybody, where the nationalists are sometimes much more based on a unilateral approach and the law of the strongest, which is not my case.”

President Macron repeated his words on Twitter:

Patriotism is the exact opposite of nationalism. Nationalism is a betrayal of patriotism. By putting our own interests first, with no regard for others, we erase the very thing that a nation holds dearest, and the thing that keeps it alive: its moral values. https://t.co/w9AltyvMDw

— Emmanuel Macron (@EmmanuelMacron) November 11, 2018

Macron’s words are notable because they stand in sharp contrast to both some troubling trends in Europe itself and the words of an American President who has shown little concern for tossing aside an international order that has kept the peace since the end of World War Two. So, the natural question, as Alissa Rubin and Adam Nossiter note at The New York Times, it’s not clear that anyone is listening:

PARIS — All week President Emmanuel Macron toured France’s World War I memory trail. He visited the killing fields of Verdun, the vast ossuary at Douaumont and the monument to heroic African soldiers at Reims. Each stop made the same solemn point: Nationalism kills.

It is a message Mr. Macron hopes will not be lost on the dozens of world leaders who will descend on France this weekend to commemorate the 1918 Armistice.

But it is not clear anyone is listening. If anything, the carefully orchestrated centennial that Mr. Macron wanted to use for boosting his image at home and his ambitions for Europe only seems certain to underscore his isolation, both at home and abroad.

The partner he had hoped to have in realizing his ambition for ”more Europe” — the German chancellor, Angela Merkel — is on her way out. The avidly nativist eastern Europeans see him as the symbol of everything that is wrong with the European Union. He extended a hand time and again to President Trump only to see it slapped away; in the last few months, Mr. Macron has increasingly been marking his distance from the American president.

All that has left Mr. Macron as perhaps the lone leader defending liberal values and European governance, and taking a moderate stance toward immigrants against flag-waving populists.

But the heir-apparent to lead Europe as Ms. Merkel exits is politically weak at home, still inexperienced as a politician, nearly outnumbered by populist leaders whose ranks are growing quickly on the Continent and lacks a partner on the world stage.

(…)

[I]n recent speeches and interviews, Mr. Macron has presented himself as the best alternative for Europe’s future as he has warned about the dangers of the increasingly loud siren song of nationalism.

“I’m struck by the resemblance between the moment we’re now living, and the period between the world wars,” Mr. Macron told the newspaper Ouest-France last week in a comparison that sparked anguished commentary.

Europe was caught between “dismemberment by the leprosy of nationalism, and being pushed around by outside powers,” he said.

Nationalism “is rising, the nationalism that demands the closing of frontiers, which preaches rejection of the other. It is playing on fears, everywhere,” he told Europe1 radio this week. Europe’s postwar peace and prosperity was merely “a golden parenthesis in our history,” he said.

But some say those characterizations miss the point of contemporary Europe’s grievances, which are less militaristic than before the world wars and more rooted in fear of how immigration is changing societies.

“Macron wants to polarize the debate,” said Dominique Reynié, a political scientist at Sciences Po and a specialist in populism.

“How can you imagine that Europe is in the 1930s now?” he said. ”Countries like Hungary are disappearing demographically. No, on questions like immigration, the Europeans are simply demanding more protection.”

But if Mr. Macron is to truly take on the role as the premier defender of Western liberal values, it becomes ever more incumbent on him to make an effort to bring his opponents into his camp even as he makes clear where his priorities differ.

Macron is to be commended for trying to use the occasion of the end of World War One to speak about something important, but between the twin challenges posted by the forces sweeping across Europe, and the domestic situation in the United States, it’s not at all certain that he will be successful.

In the first regard, political parties that espouse nationalist, anti-European themes have risen to power in Eastern Europe, most notably in nations such as Poland and Hungary, both of which are currently controlled by right-wing nationalist parties that espouse right-wing populist themes that have become openly hostile to immigrants and to influences beyond their own borders. In other parts of Europe, including Austria, The Netherlands, Italy, Greece, and France itself in the form of the National Front, political parties with decided nationalist, anti-immigrant, messages continue to exist and, in some cases, appear to be gaining power. In Germany, the most recent round of elections witnessed an increase in the political influence of the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party more than triple the share of the vote it received from 4.7% in 2013 to 13% in 2017. And, finally, of course, there is the ongoing Brexit process, a move by the United Kingdom to toss aside the European Union that threatens to unravel the entire E.U., an organization that has arguably succeeded quite well in its underlying purposes of uniting the continent and discouraging the revival of the kind of poisonous nationalism that led to war in the 1910s and from 1939 to 1945.

In the second regard, there is the fact that the United States, which has played a crucial role in keeping the peace in Europe for more than seventy years, may be straying from the path itself. This came up most recently when the President used the occasion of one of his many appearances on the campaign trail to announce that he considered himself a “nationalist.” Here in the United States, that claim brought many to draw an equivalence between the President’s rhetoric and that of the white supremacists of the alt-right. When questioned about that aspect of his rhetoric, he responded, bizarrely, by claiming that it’s racist to even ask the question. In addition, this President has taken every opportunity to drive a wedge between the United States and its most loyal allies, something I’ve made note of here, here, and here. He has also, foolishly taken us down the trade war route based on the foolish idea that “trade wars are good and easy to win,” In doing so, he has effectively turned back the clock and opened the door to the kind of poisonous nationalism that President Macron rightly decried and against which so many fought not only in the so-called “War To End All Wars,” but in those that have followed in its footsteps.

As Ishaan Tharoor notes, Trump’s evocation of “nationalism” is a direct challenge not only to Macron’s vision, but also to the world order as it has existed since 1945, and as it should have been after the guns fell silent 100 years ago today:

Macron wants that story of unilateralism and conflict to be a cautionary tale for his contemporaries. “A survival-of-the-fittest approach does not protect any group of people against any kind of threat,” he said recently.

“We in the West, in particular, have been extremely lucky. We’ve lived through an extremely long period of peace,” said Oxford historian Margaret MacMillan to my colleagues. “The worry is that we take peace for granted and think it’s a normal state of affairs. We should reflect that sometimes wars do happen — and sometimes not for very good reasons.”

That message is unlikely to get through to Trump. His treaty busting and ally bullying have strained trans-Atlantic ties and encouraged Europe’s anti-establishment forces. His overt nationalism and embrace of protectionism, critics say, have undermined American leadership and called into question the future of the international order constructed by the United States after World War II.

Ivo Daalder, a former U.S. ambassador to NATO and co-author of “The Empty Throne: America’s Abdication of Global Leadership,” said that while Trump and his counterparts are celebrating the end of what’s known as the Great War, they should “also reflect on America’s greatest mistake.” That is, a decision to eschew the internationalism of then-President Woodrow Wilson for the isolationism of his interwar successors.

Trump’s “America First” agenda also harks back to that historic withdrawal, when skepticism about foreign entanglements and fear of immigrants defined national policy at home and abroad. This circling of the wagons had significant geopolitical consequences.

“In the 1920s, conservative Presidents Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover rejected both binding alliances and the notion that America should make economic sacrifices to uphold the geopolitical order,” noted the Atlantic’s Peter Beinart in an essay earlier this year. “They saw little difference between Britain and France, which were more democratic, and Germany, which was more authoritarian,” he continued, “and insisted that America remain independent from them all. They opposed Woodrow Wilson’s dream of requiring America to aid European nations threatened with aggression through the League of Nations.”

In 1919 and 1920, the U.S. Senate rejected signing the Treaty of Versailles and joining the League of Nations, the new international organization intended to stave off future bloody catastrophes. The American absence possibly doomed the project at its birth.

“Why would other societies invest in the agreement if one of its leading proponents, also one of the emerging world powers, refused to participate? Many observers appreciated the domestic politics behind the U.S. rejection of the treaty, but that only deepened long-standing perceptions that the United States was an unreliable partner,” wrote Jeremy Suri, a historian at the University of Texas at Austin. “Why should others tie their hands if the United States acted as a free rider? In the decade after the First World War, U.S. actions encouraged unilateralism by other powerful actors, especially Japan, Germany, and the newly formed Soviet Union.”

“For nationalists like John Bolton, Trump’s national security adviser, the League’s failure has become a byword for the futility of global governance,” wrote Gideon Rachman of the Financial Times. “In the 1930s, the League was completely unable to act as an effective check on the ambitions of imperial Japan, Mussolini’s Italy and Nazi Germany. The realist-nationalist view is that it was only hard power deployed by nation states — rather than global governance deployed by international institutions — that stood a chance of checking the ambitions of dictators.”

But this view gets it precisely backward, Daalder argued. It was the effects of American disengagement after World War I that convinced the next generation of U.S. strategists to build the international institutions and security pacts that defined the latter half of the 20th century and brought lasting peace to Europe. Now, as Daalder and his co-author James Lindsay write, Trump’s reckless foreign policy is hastening a new era of “ever-growing disarray” or even a “return to the world of the late 19th century” — the tinderbox that exploded into World War I.”My big fear is that the return to nationalism and protectionism is likely to deepen divisions between countries, to erode norms and standards of behavior, and erode the element of cooperation that has been fundamental to U.S. security and prosperity,” Daalder told Today’s WorldView. “We know what great power rivalry looks like. We know where it ends up.”

The First World War began thanks in no small part to nationalist tendencies that made a conflict seemingly inevitable. In the beginning, everyone seemed to think that it would be over in short order and that it would end in much the same manner that the wars of the 19th Century did, with some kind of realignment of power on the Continent. Instead, thanks in no small part to the technological advances in warfighting that had been made since the days of the Napoleonic Wars, it quickly devolved into a stalemate that lasted four years and which brought forward horrifying developments such as trench warfare, mass casualties, and chemical weapons. By the time it was over, the old order in Europe was gone. The Russian Empire had been toppled by a revolution that would define the latter half of the 20th Century. The German Empire dissolved in defeat and its territories carved up in a manner that would create resentments for the next two decades. The Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires were carved up the Allied forces. creating new nations in Europe and the Middle East and borders that are causing political problems to this day. The United States tried to retreat back across the Atlantic, but that would prove to be impossible as the new order in Europe created problems for everyone and a new threat developed in the Pacific. And the peace imposed at Versailles would lead to resentments in Germany that brought to power one of the most destructive regimes in world history and led to the worst war in human history. There arguably would have been a conflict in Europe in the early 20th Century regardless of whether Franz Ferdinand lived or died, and at the very least it seems apparent that the old tired empires in Vienna and Constantinople would have collapsed at some point with or without a war. However, it’s also clear that the world we live in would be significantly different had World War One not unfolded when and how it did. And it all started on a June day in Sarajevo when one Bosnian Serb took a shot at a guy wearing a rather ridiculous uniform. Now, we seem to be slipping back into a time where all those events, and the second war that followed in the footsteps of its older cousin, are being forgotten. The siren song of nationalism is distracting people again, and the consequences this time could be disastrous.

That photo above of Trump is breathtakingly representative of who and what he is: A fat, slump-shouldered, resentful, surly buffoon completely out of his depth, utterly incapable of understanding the world around him, enraged and pouting because he’s despised by everyone but the yahoos he himself despises.

It’s remarkably naïve that you think nationalism is a first cause; but then you also think a country with racial laws the Nazis considered too harsh is the land if freedom.

CSK: Small children insult others’ physical appearance.

The term “nationalism” has had different meanings over time, and to some extent many of the countries of modern Europe were originally formed from nationalist movements. One of the problems with applying the concept to the USA is that the USA has never been associated with any particular ethnic group. (People talk about ethnic Italians or ethnic Germans. What exactly is an “ethnic American”?) Whatever else the Declaration of Independence is, it’s not a nationalist document. There is certainly a tradition of racial exclusion in America (for historical reasons the OED still includes as one of its definitions of American, “native of America of European descent”), and that’s almost always what nationalism in an American context ends up amounting to, even when it doesn’t come with the word white explicitly attached.

It’s important to recognize that unlike leaders like Macron and Merkel and Trudeau, Trump has no understanding of history, and if he did understand it, he wouldn’t care. It useless trying to apply logic to Trump’s actions or statements, he only has one metric: is it good for me? I mean this quite literally: Trump is not capable of caring about anyone or anything but himself. It is a waste of effort trying to understand him as a human being, it really is much more useful to think of him as a predatory animal. He has exactly the same emotional depth as a shark. He has exactly as much concern for people other than himself as a tapeworm might have. He has less of a sense of justice than has been observed in chimpanzees. I’ve said it before: he’s a psychopath. A rather stupid one.

So let’s not waste too much time bemoaning the fact that he behaves like a selfish pig, utterly indifferent to the sacrifice of American and allied (and indeed German) lives. He doesn’t care. He can’t. He’s a sick man.

@Ben Wolf:

And, quite often, they speak the unvarnished truth.

@Ben Wolf:

The above is a deliberately misleading statement. The kind of thing an idiot troll might say. You grow more sophomoric by the day.

We did learn from WWI when we settled WWII, which was in many ways WWI 2.0. (It helped that we wanted our recent enemies in the fold against our recent ally.) We didn’t crush the defeated with reparations. We didn’t redraw borders to create horrors of ethnic conflict. We tried war criminals, but imposed no collective punishment. We did push democratic governments on them, much like our own. We aided them economically. But most importantly we established relationships and international institutions to prevent a recurrence. That was two generations ago. We seem to be forgetting.

My views on WW I are congruent with the views of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. It was a massive failure of Western Civilization resulting in death, destruction, and mayhem on an unimaginable scale for no good reason. This totally delegitimized that civilization and caused people to seek alternatives which sadly included Soviet Communism and German Nazism.

Reading recommendations:

Wilfred Owen Dulce et Decorum Est

Sassoon Suicide in the Trenches

@gVOR08:

The Middle East would beg to differ. For better or for worse, the state of Israel is a direct consequence of such behavior and it has ethnic conflict a-plenty.

To be fair, I don’t think there was a way it could have been done without ANY conflict whatsoever but it seems to the world kinda slept through the finer details of that particular lesson…..

All of the warnings of nationalism will fall of deaf ears for Trump. He thinks nationalism is a good thing, rather than ill conceived libertarianism for countries.

Also, there is this: https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2018/11/baltics-vs-balkans-trump-reportedly-gets-the-two-confused-at-meeting-with-leaders-of-estonia-latvia-and-lithuania.html

I will confess the names are similar, but shouldn’t he know something about the region his wife comes from? Ok, not 100% sure I believe that story, but I’m not sure if it is a reasonable doubt or wishful thinking.

@gVOR08: WWI was indeed a family fight. Most of the leaders were related and got to a point where they refused to talk to each other, much like what many of us see at the holidays. The big truck in the room was Russia, which got taken out by the Communists. There are good arguments that if Russia had stayed in the war would have ended sooner and a more equitable peace would have taken place. There are good arguments both ways on US involvement.

The big lesson is that world leaders sometimes need to take a step back and think. Also a world war can start over a seemingly unimportant place.

What changed after 1945 was the founding of several international institutions that tie various countries together. It’ not just the UN, WTO, and the EU, but also things like the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and even the International Air Transport Association. And also the idea that war between the major powers had become too destructive, and fighting such a war with nuclear weapons would be disastrous for the world. The plethora of institutions and the ties they create are one means of keeping the peace.

Most countries regard peace as being in their own interest. Certainly peace between the great powers, or in this day and more accurately nuclear powers, is paramount to global prosperity. That’s why the Cold War stayed relatively cold (yes, I know many countries suffered fighting the proxy wars of this era).

The problem in the age of Trump, is that he doesn’t seem to regard either peace or the avoidance of humanitarian crises, as being in his country’s self-interest. As far as Trump is concerned, the only things that seem to matter are trade balances and how much money he gets paid or he can claim to bring into the country.

He may not have an apetite for war, as yet, though he is reported to have proposed using force in Venezuela and is fond of brinkmanship, but he’s reshaping the world to make war more likely in the future.

@Ben Wolf: Small children insult others’ physical appearance.

First, the comment spoke mainly about body language. But moreover, shall I compile a list of the times Trump has ridiculed physical appearance? Disabled reporters, porn stars who are getting the better of him, female political opponents, political opponents’ wives, women reporters, Miss Universe contestants (!), his sexual assault accusers, Cher…

@Michael Reynolds:

Although I gave your comment a thumbs up, I don’t think “sick” is quite right. To me he is more of a partial person, someone with big gaps in his psychology. Under normal circumstances, when someone is born and new to the world they don’t have empathy or a sense of fairness or the concept of having obligations outside of one’s immediate circumstances. They can’t control their emotions or hold themselves back from lashing out when upset. But over time they gradually develop those capabilities as they grow into a complete human being. Trump seems to have stopped developing mentally at about the age o f 10 – 12. If he’s “sick” it is that he is stunted. He grew to a certain point and then never got any father. He is incomplete.

@MarkedMan:

Sick as well as stunted, I believe. Trump takes great pleasure in crushing his opponents, especially when they’re too old, ill, disabled, or poor to fight back.

@Ben Wolf: I suspect that if a Democratic POTUS had bloated up as much as Trump has over the past two years, every other comment on Fox would be chastisement for lack of self-control.

The guy is a slob who scarfs down fast food while getting no exercise and yells at everybody. Why shouldn’t I disdain his lack of cooth?