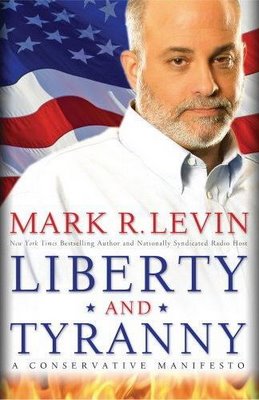

Blogging Liberty and Tyranny, Chapter Four

Examining Levin's examination of the Constitution, jurisprudence, and property rights.

Chapter 4 – On the Constitution, pp. 36-48

Mark Levin has a law degree from Temple, has served in a legal capacity to the government and practiced as a private attorney. So I’ve actually been looking forward to reading his chapter on the Constitution. Whatever ignorance Mark Levin may display about history in his book, surely his treatment of the law and jurisprudence should have a nuance and thoughtfulness that you’d expect from someone who has expertise in the field, right?

Alas…..

We begin with a typical Levin non sequitur —

Language consists of words, words have ordinary and common meanings, and those meanings are communicated to others through the written and spoken word.

I don’t know why Levin keeps kicking off his chapters with this kind of pseudo-intellectual sounding nonsense sentences. Note to Mr. Levin: the ability to write a complex sentence is not, in and of itself, an expression of intelligence. The sentence still needs to be coherent and understandable. Additionally, brevity is always appreciated. Indeed, some thoughts don’t require communication at all. For example, the target audience for a book always includes people who are literate. It’s a fair bet that literate people are familiar with the concept of “words.”

But I digress.

Levin then goes on to explain that a Conservative (always with capital C, by the way, which annoys me to no end) “believes that much like a contract, the Constitution sets forth certain terms and conditions for governing that hold the same meaning today as they did yesterday and should tomorrow.” He then notes that “[t]o say that the Constitution is a ‘living and breathing document’ is to give license to arbitrary and lawless activism.”

As a point of fact, I don’t disagree with this. At all. Indeed, most legal scholars — left, right, libertarian and socialist — pretty much agree on this fundamental point. Indeed, I think Levin might actually be surprised to learn that in the realm of legal jurisprudence virtually nobody disagrees with this. Levin continues by stating that

The Conservative seeks to divine the Constitution’s meaning from its words and their historical context, including a variety of original sources — records of public debates, diaries, correspondence, notes, etc. While reasonable people may, in good faith, draw different conclusions from the application of this interpretative standard, it is the only standard that gives fidelity to the Constitution.

Once again, I don’t disagree with Levin. And again, very few legal scholars do! Now, if you thought this was going to lead into a nuanced discussion of the difference between the conservative interpretative framework championed by, for example, Justices White, Black and Scalia against frameworks by Justices such as Brennan, Holmes, and Brandeis well — you forgot whose book we were reading.

Once again, the Statist boogeyman appears. And this time — HE’S COMING FOR YOUR CONSTITUTION!!!!

The Statist is not interested in what the Framers said or intended. He is interested only in what he says and he intends.

Paging Mr. Pot. Mr. Pot… are you there?

Consider the judiciary, which has seized for itself the most dominant role in interpreting the Constitution.

I love how he used the word “seized,” as though there was some sort of recent coup, and not something that happened in 1803’s Marbury v. Madison decision. A Court decision that was, I might add, penned by John Marshall, who was part of the Virginia delegation that recommended to the House of Burgesses that the Constitution be adopted. (Defeating his political rival, Patrick Henry.) He was joined in this decision by William Paterson, who signed the Constitution; Samuel Chase, who signed the Declaration of Independence; and Bushrod Washington — George Washington’s nephew. I have a feeling that these Justices might have had some inkling of “what the Framers said or intended.”

Levin then goes on to criticize the jurisprudence of Justices Marshall and Goldberg for pursuing the “just result” as an approach for interpreting the Constitution. Seriously, I’m not kidding. This is a serious complaint. In Mark Levin’s world, the pursuit of justice is apparently not the job of a Supreme Court Justice!

This is, of course, an absurd position. One of the stated goals of the Constitution, as stated in its own preamble, is to “establish Justice.” Using justice as a criteria for Constitutional interpretation is right there in the text!

Levin then extends this criticism:

Or is not the Statist saying that the law is what he says it is, and that is the beginning and end of it? And if judges determine for society what is right and just, and if their purpose is to spread democracy or liberty, how can it be that the judiciary is coequal with the executive or legislative branch?

There’s a lot of nonsense to unpack in this statement. Clearly, when Justices Marshall and Goldberg referred to pursuing a just result, they did not claim that they were not bound by the law, nor did they claim to “determine for society what is right and just.” In any case that occurs before a Court, there is always a dispute. The role of a judge is to settle the dispute based on the law, and he is to interpret that law through the use of judicial precedent. But it is a long, long tradition in Anglo-American jurisprudence that judges take into account the justice of a situation when making their decision. Indeed, the Common Law is nothing but judge-made law designed to reach just results.

Based on this tradition, we trust the judge’s discretion and prudence to interpret the law in such a way as to produce a just result. Now, sometimes a judge can’t — there may be no way to interpret the law other than to reach a just result. And when that happens, you’ll often see a judge opine in favor of the aggrieved party even as the judge rules against that party. But when you have several valid interpretations of a law, a judge should go for one the produces the best result.

No doubt, this is a messy process. It’s a process that doesn’t always lead to consistent decisions and it adds a layer of risk to litigation. But relying on a judge’s discretion to find a just result is a principle that’s served the United Kingdom, the United States, and other Anglosphere countries well. What Levin seems to desire, on the other hand, is a rigid and literalist school of legal interpretation. This type of school, however, is a profoundly un-American one (in a historical sense) and much more in keeping with the Civil Law traditions of most European nations.

Also, and equally funny to me, where in the Constitution designated as “coequal with the executive or legislative branch”? Go ahead, I’ll wait while you look it up.

Couldn’t find it? That’s because it isn’t there. The idea that the branches of government are “co-equal” is an interpretation of the Constitution. It’s not in the original text.

After this, Levin keeps the Statist boogeyman going, ending with quite possibly my favorite line in the book so far.

And the Statist on the Court tolerates representative government only to the extent that its decisions reinforce his ends. Otherwise, he overrules it.

This is my favorite because I’m not sure where he’s going with it. Is Levin trying to say that any judicial decision that overturns a law passed by a legislative body is bad? Even if that law conflicts with the Constitution? He sure seems to imply that, doesn’t he? But this point goes unaddressed for the remainder of the chapter. Too bad, because I’m interested in learning whether this only applies to liberal decisions.

Levin then goes on to continue his previous attacks on Franklin Delano Roosevelt. In particular, Levin attacks Roosevelt’s “Second Bill of Rights” speech, which was Roosevelt’s speech in 1944 in favor of more economic justice in the United States. Regardless of what one thinks of the merits of FDR’s policies, Levin’s attacks are hyperbolic and nonsensical.

This is tyranny’s disguise. These are not rights. They are the Statist’s false promises of utopianism, which the Statist uses to justify all trespasses on the individual’s private property. Liberty and private property go hand in hand. By dominating one the Statist dominates both, for if the individual cannot keep or dispose of the value he creates by his own intellectual and/or physical labor, he exists to serve the state.

I’m sorry, but this is crap. I will grant you that a Communist state, one where there is no private property at all, is inevitably going to be totalitarian. No question there. But Levin’s inability to distinguish market liberalism from Communism exposes a complete misunderstanding of the nature of both.

Let’s be clear on this. Property rights are important. Property rights should, to a certain degree, be respected. But they’re not inalienable, and they’re not on the same level of fundamental human rights such as freedom of speech or freedom of religion. Indeed, government can’t exist without some abrogation of the rights of property. Taxes violate the right of property. Eminent domain violates the right of property. The Constitution provides for both. Frankly, if you believe in absolute property rights, you can’t believe in government at all. Anarchism is the only logical end of a belief in absolute property rights.

This distinction between fundamental human rights and rights to property is one that many of the Founding Fathers’ acknowledged. Thomas Paine, for example, in his Agrarian Justice, argued that ownership of land was a social convention, and that nobody had a natural right to own it. Thomas Jefferson was well-read in Locke, but changed Locke’s formulation of “life, liberty and property” to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Moreover, note that Levin includes in his formulation of property rights the “protection of intellectual… labor.” But this is another point where many of the Founding Fathers would disagree with Levin. The Constitution doesn’t allow for the protection of intellectual property as a matter of right. It allows for such protection in order to “promote science and the useful arts.” In other words, intellectual property is merely seen an an instrumental tool to improve social well-being — not a right to be protected. Indeed, Thomas Jefferson opposed any such intellectual property right as all. Despite being a prolific inventor, Thomas Jefferson said, in a letter to James Madison, that:

He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me. That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation. Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property.

Given that Levin has lauded Jefferson on several occasions thus far in this book, I doubt that Levin considers him a “Statist.” However, Levin’s views on private property are positively radical compared to those of Jefferson and many of his contemporaries.

The next four pages consist entirely of Levin denigrating the work of Robin West, Cass Sunstein, and Bruce Ackerman. But he doesn’t provide any reason why. He simply assumes that it’s self-evident that their ideas are wrong. (In fact, he quotes a long passage from Cass Sunstein about the reality of the role of the government in the economy that I couldn’t actually find fault with.)

Levin then actually tries something interesting. He actually makes an argument, rooting his argument for property rights in a natural law theory.

What differentiated man from the rest of the animal kingdom was, in part, his ability to adapt his behavior to overcome his weaknesses and better master his circumstances. It is how he makes his home, finds or grows food, makes clothing, and generally improves his life. Private property is not an artificial construct. It is endemic to human nature and survival.

I’m actually almost so flabbergasted that Levin’s making an argument here that I’m tempted to just leave it be, the way you put a 2 year old’s first drawing on the fridge without criticism, because it’s neat that they did something besides just scribble randomly.

But I can’t leave it be. I can’t. Because it’s wrong.

Here’s the thing — private property is an artificial construct. Human beings, by nature, are not farmers and city builders. They are hunter-gatherers. And virtually every hunter-gatherer society in history has communal, not private, property. What we think of as civilization — property, hierarchy, laws, science — are products of agriculture. (Jared Diamond has some excellent work on this very subject — I’d encourage that you read it.) Because agriculture forces human communities to remain rooted in one place, rather than nomadically following food, property was a development that enabled society to work. As Thomas Paine explains in Agrarian Justice:

There could be no such thing as landed property originally. Man did not make the earth, and, though he had a natural right to occupy it, he had no right to locate as his property in perpetuity any part of it; neither did the Creator of the earth open a land-office, from whence the first title-deeds should issue. Whence then, arose the idea of landed property? I answer as before, that when cultivation began the idea of landed property began with it, from the impossibility of separating the improvement made by cultivation from the earth itself, upon which that improvement was made.

Property rights, then, are a product of civilization — they are not endemic in the human condition. This doesn’t mean that property rights don’t exist at all, nor does it mean, as the radical leftists of the 60s put it that “all property is theft.” I would argue that one’s work in trade does produce a property right, and that the fruits of one’s labor should be protected from predation and theft. Nevertheless, not everyone’s property is produced through one’s labor. You might receive a gift. You might inherit. There is no natural means of deriving these rights — they’re simply respected through law and custom. As such, they are rights that are secondary to the more fundamental rights of life and liberty. Property rights are only worthy of protection insofar as they promote the general welfare of society. This was the position of the classical liberals of the Enlightenment, and is still the position of most modern liberals today. Levin’s view is a radical departure from Enlightenment thinking.

Indeed, Levin views people who share this way of thinking as

an arrogant lot who reject the nation’s founding principles. They teach that the Constitution should not be interpreted as the Framers intended–limiting the authority of government through “negative rights,” that is, the right not to be abused and coerced by the government; instead, they urge that the Constitution be interpreted as compelling the government to enforce “positive rights”

First of all, it’s false on its face to assume that Framers intended the Constitution merely as a means of protecting “negative rights.” The Constitution’s goals are defined in the preamble as:

to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity

This goes beyond merely “protecting rights.” Indeed, the Constitution had to be amended to force the government to protect free speech, freedom of religion, etc. And its clear that the early Founding Fathers had a vision of the country that went beyond Levin’s. Let’s take a look at the first ten years of our nation through the eyes of the first Five Congress’s. All of them passed at least one major piece of legislation that went beyond merely protecting the “right not to be abused and coerced by the government.”

- The First Congress passed an Act establishing the First Bank of the United States. A controversial institution whose goal, promoted by Alexander Hamilton, had the goals of providing a single unit of currency in the country, establishing credit for the United States, and resolving debts based on the currency issued by the Continental Congress. None of these goals had anything to do with protecting rights and had everything to do, in the eyes of Congress, with promoting the general welfare.

- The Second Congress passed the Postal Service Act, which established the United States Post Office. Again, this was all about promoting general welfare and not protecting rights.

- The Third Congress passed several laws directing the building of lighthouses along the East Coast.

- The Fourth Congress passed a law empowering the President to use the armed forces to enforce quarantines as necessary.

- The Fifth Congress passed the Marine Hospital Service Act, which established Federal hospitals for civilian merchant seamen and made other provisions for their relief and health.

As you can see, Levin’s idea that the intent of the Founding Fathers was to establish a government whose sole purpose is to protect rights is proven wrong by both the words of the Constitution itself and the acts of the first Congresses. The examples I listed above are just a fraction of the laws that were specifically adopted to improve the country — not merely to protect rights.

Indeed, Levin’s entire thesis, throughout this chapter, demonstrates that is political philosophy is not that of the Enlightenment classical liberals, but rather has its roots in the radical libertarianism that developed in the 1930s as a reaction to Roosevelt. Levin’s “conservatism” is the philosophy of Albert Nock, Isabel Paterson, and Rose Wilder Lane — NOT Washington, Hamilton, Madison, Adams, Paine, and Jefferson. And that’s fine, as far as it goes. If Levin wants to argue for his version of radical libertarianism, I’m willing to hear those arguments.

But the problem is, he doesn’t make those arguments. He makes assertions about the “way things ought to be”, wraps them in a flag, chisels them in stone, and pretends that the Founding Fathers delivered his philosophy from God, as spoken to his prophets on Mount Vernon. It’s dishonest and disgusting. And frankly, libertarians and conservatives both would do better to repudiate Levin’s dishonest defenses of their principles.

Levin closes his chapter with a quote from Frederic Bastiat. I’ve never cared for Bastiat, so I’d rather close with a quote on the importance of the judiciary from our first President, George Washington.

“Impressed with a conviction that the due administration of justice is the firmest pillar of good Government, I have considered the first arrangement of the Judicial department as essential to the happiness of our Country, and to the stability of its political system; hence the selection of the fittest characters to expound the law, and dispense justice, has been an invariable object of my anxious concern.”

Next time – we explore Levin’s thoughts on Federalism. Be there!

Screw waterboarding. Read this stuff to the prisoners at Gitmo, and they will crack…

“It’s dishonest and disgusting. And frankly, libertarians and conservatives both would do better to repudiate Levin’s dishonest defenses of their principles. ”

A few brave righties have called out Levin’s crap, Jim Manzi and David Frum come to mind.

I’m not sure it matters, though.

Famous wingnut puts out some kind of “book.”

Famous wingnut’s fans rush out to buy it because???

A kind of “thank you” for sticking it to the “libruls?”

They just can’t get enough of famous wingnut’s shtick?

Presents for those difficult to shop for cray relatives>?

I’m curious, Mr. Knapp: has Levin made any mention of your reviews yet? I’d love to hear his reaction, mainly because I find everything the man says absolutely hilarious.

>Mark Levin has a law degree from Temple, has served in a legal capacity to the government and practiced as a private attorney.

This is something I find fascinating about many right-wing bloviators, that they seem more ignorant than their education would lead us to expect. It’s like Bill O’Reilly, who has a history degree and taught history to high school students, then he says stuff like that Thomas Jefferson would mock the “secular fools” who “hide behind the bogus separation of church and state argument that does not appear anywhere in the Constitution.” And O’Reilly is clearly smarter than Mark Levin.

That’s among the reasons I suspect people like Levin are not idiots, they just play one on TV (or radio).

This is your best chapter yet.

>A few brave righties have called out Levin’s crap.

One of the things that drove me nuts when I was growing up in the ’90s was the failure of conservative intellectuals to repudiate the intellectual bankruptcy of clowns like Limbaugh. Buckley merely admitted that Limbaugh “induces hatred,” and that “if I were a liberal I would hate him”–as if Limbaugh’s chief sin was being mean to liberals, rather than lying to his audience and presenting a distorted picture of the world. Levin is a poor man’s Limbaugh, yet any conservative who attacks him is effectively cast outside the conservative movement.

>I’m curious, Mr. Knapp: has Levin made any mention of your reviews yet?

If he does, I’m dying to know what third-grade insult he comes up with to abuse Mr. Knapp’s name. After Friedersdork and Andrew Swampland (really?), I’m sure Alex Knapp should be a piece of cake.

To my knowledge, Levin has not mentioned these reviews. I suspect that we will know if he ever does by the comments.

I keep linking them to his Facebook page. He gets a lot of traffic,but you never know:)

“Indeed, government can’t exist without some abrogation of the rights of property.”

Not to quibble, but government can’t exist without some abrogation of the fundamental rights to life, liberty, freedom of speech and freedom of religion, either. You are correct that Levin and company have fetishized property rights, but I think ownership is a bit more fundamental to the modern framework of rights and liberties than you’re making out. And I’m not sure the understanding of intellectual property from 200+ years ago is necessarily the one that should guide us today, given the difference in revenue generated from IP then and now, if nothing else.

Mike

@G.A. – I have noticed that you, among others, have posted my blog reviews on Levin’s page. However, they are typically removed within an hour.

@MBunge – I didn’t mean to imply that property rights are unimportant, but I think the difference in the abrogation of property rights compared to other rights in order to sustain the function of civil society is big enough to be a difference in kind. As for intellectual property rights, they started during the Elizabethan Era in Anglo jurisprudence, so there was already a long history at the time of the Founding.

Additionally, I might add that I don’t agree with Jefferson’s view of intellectual property rights. My point was merely that Levin is claiming the mantle of the Founding Fathers to support his views, even though they didn’t agree with him.

“I don’t know why Levin keeps kicking off his chapters with this kind of pseudo-intellectual sounding nonsense sentences”

Because he wants to be mistaken for a philosopher, and a legal expert.

I am not well versed in the theory of property rights, or the current SCOTUS interpretation of it. What I believe is that a takings for the purpose of turning the property over to commercial developers, in part or in whole, and thus eventually producing more tax revenue for the state, and thereby doing something for “the general welfare,” is very simply unjust. How does this fit into your interpretation of property rights as secondary, especially if the property has an income or livelihood aspect for the current owner?

@manning,

I agree with you on this 100%. The Constitution only allows the government to take property for “public use,” and I honestly don’t see how stealing a Church and replacing it with a Wal-Mart is a “public use.”

Even if you could convince that it’s Constiutional (I don’t think it is), you could never convince me that’s it’s either good policy or a just policy.

>Do not use the cowardly method you use of hiding in the echo chamber, where you know you

will get positive feedback as your platform.

It is sentences like this for which the word “irony” was invented.

A new rule for “conservatives” — Not only must you never speak ill of La Palin, you are forbidden to criticize the published writings of any right-winger, except in private to his face. He allowed his words to be published so the world would have the benefit of his wisdom, not so he could be challenged.

So says Zels “I’m all about freedom!” Raghshaft.

Thanks for my (so far) favorite installment in a good series.

At the risk of another nerdy reference, I would humbly suggest that Mr. Levin’s grasp of history and human sociopolitical development could be improved quite a bit by playing Civ 5. It certainly seems that the more rigorous and accurate methods of, well, studying history, seem to be beyond him. How can one not understand that the concept of private property arose because of agriculture?

I agree that Mr. Levin’s principles have little to do with the principles of Enlightenment thought which influenced the Founders. Unfortunately, the same can be said for a good number of these dumbed down conservative pundits who seem entrenched in a confusing tangle of theological-statist, nationalist and libertarian positions that can only be maintained by issue-oriented ideological blindness.

@ Alex

This review has been a truly insightful comentary on “Levinism” in general.

I am somewhat embarassed to admit that I read through this book of Levin’s at a furious pace, and only managed to feel a few jangles and jars and a certain disquiet overall. I had planned a second, more careful read to track down those signals, which is my usual practice, but even then I believe I would not have picked up on nearly as many contretempts as you have done so far. Perhap I will spend the effort, simply to tune up my jangle/jar detector. Bravo!

@Mannning 0

Thanks for the kind words. Glad you’re enjoying the series. This has been an interesting exercise for me because, as I mentioned, I don’t really pay attention to the mainstream pundits. Truly eye-opening.

@ Alex

While I can see where property rights are inferior to life, human rights, and maybe the pursuit of happiness, it is my belief that the right to individual property ownership is absolutely essential to liberty, and as such, must be defended very strongly indeed by the law and by custom. Would you agree here?.

mannning –

I wouldn’t disagree with that. But I see property rights more through the lens of social utility within the hierarchy of rights. I would argue that it’s a grosser violation of rights to let poor people starve than to tax me to pay for food stamps. Now, that doesn’t mean that food stamps are the best policy, etc etc. Plenty of room for debate about policy. But as a matter of right, I don’t think my right to my money trumps letting someone starve.

This is obviously a careful line to draw, because history shows us that going all in on communal property rights leads to an awfully vicious tyranny. But I wouldn’t say that, for example, Denmark is a hotbed of totalitarianism because it has universal health care.

Does that make sense?

“But I see property rights more through the lens of social utility within the hierarchy of rights.”

Isn’t that because property rights, in the basic sense, are relatively unchallenged in the post-Communist world while other so-called fundamental rights remain more in dispute? Or to be more accurate, we focus our attention on the more intangible rights in our present day discussions of freedom and liberty.

Take Egypt for example. Those folks are now exercising what we would call their right to speak and assemble, yet if their efforts fail it will likely be due to their lack of economic power. Or consider China, where the promotion of economic freedoms has long been thought to be the key to the propagation of other forms of liberty (which doesn’t necessarily seem to be working like expected).

Mike

I struggled with this statement. I believe you have a particular circumstance in mind, such as facing a beggar that obviously needs some money to eat. This is an act of charity that most would accept.

Generalizing from this, however, gives me great difficulty. Should the US, given that it has excess revenue, or should it create substantial funding, and pass it all along to needy, starving millions in poor nations? Who has the greater right to this excess money? We obviously do not allocate any huge funds for this purpose, or else our economy would not expand. Do we have an obligation to take on the feeding of all of the millions and millions of starving peoples that have rights to eat?

mannning –

I struggle with this same issue myself. At some point, you can’t give away all your money or you’re right — the economy doesn’t expand.

It’s a balancing act. How do we maintain economic growth without leaving people behind? That’s the tricky policy question, and it’s one that doesn’t lend itself to easy ideological answers.

“Generalizing from this, however, gives me great difficulty.”

I saw someone else on line who pointed out that one of the intellectual black holes conservativism, and particularly libertarianism, has fallen into is always, always, always thinking that everything has to derive in a straight line from first principles.

Mike

Alex-

For what it’s worth, I’ll check out his show on my way home from work every now and then, and he has mentioned you. Not by name of course because he doesn’t want to have any listeners accidentally find you. I believe he called you “a little twerp.”

Enjoying the series. Can’t wait for the Glenn Beck review. Two of my relatives that disagree on everything politically agreed to read a book suggested by the other. The conservative chose Beck’s Common Sense for him. He said he felt he got dumber after reading it because it put so many wrong and dumb ideas into his head.

The liberal chose Sacred Hoops by Phil Jackson. He’s still waiting for the conservative to read it.

I must admit that trying to derive a straighline from first principles is an effort I undertake up front. However, if one can derive the impossibility of arriving at a straightline derivation, then it is mere intellectual honesty to admit it, and then to attempt to find operative principles that do no real violence to the general welfare or the first principles themselves. This is simply common sense.