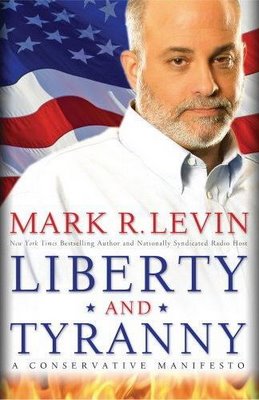

Blogging Liberty and Tyranny, Chapter Five

Taking a dive into Mark Levin's view of Federalism.

Chapter Five – On Federalism, pp. 49-60

Before I start this chapter, I have a feeling that I’m going to be bored. This is probably going to be a short entry, because I find it hard to get exercised one way or the other about federalism. Then again, maybe Levin will make me go on a long digression, we’ll see.

We open with a description of the Constitutional Convention that is fairly accurate. A good start so far.

After a first paragraph in which describes the intent of the Framers’ in terms of a national government, he underscores the importance of the delineation of state and federal power by referencing the Tenth Amendment. (Which, of course, was not adopted in 1787, but rather ratified by the states after the adoption of the Constitution, but both Madison and Hamilton considered the Tenth Amendment to be superfluous so I’ll let this point slide.)

Next, Levin notes that “States are governmental entities that reflect the personalities, characteristics, histories, and priorities of the individuals who inhabit them.” This is true, as far as it goes. But states are also arbitrary lines on a map, reflecting two centuries of compromise over slavery and the western territories, some of which make more sense than others. There’s nothing really special about them. Consider this: HALF of the population of the state of New York, 8.4 million, lives in New York City. That’s a larger population than 38 of the 50 states. The ten least populated states, COMBINED, have a smaller population than New York City. So why is New York City “just” a City, while much smaller political entities are considered states? Just the circumstances of history. There’s no rhyme or reason to it.

Indeed, it’s this strange and arbitrary makeup of the states that led Alexander Hamilton to walk into the Constitutional Convention with a plan that virtually eliminated state sovereignty entirely.

Next, Levin makes the usual paeans to Federalism, which we’ve all heard before, but let’s let him talk:

States are more likely to better reflect the interests of their citizens than the federal government. Localities are even more likely to better reflect these interests because the decision makers come from the communities they govern–they are directly affected by their own decisions.

A couple things worth noting here.

1. These are empirical arguments. If they’re true, we ought to be able to somehow make a determination that this is so. But Levin doesn’t do that–he just asserts it.

2. This begs the question — why have a federal government at all? Levin’s only support, so far, seems to be that the Founding Fathers wanted it that way. I’m interested to see if he defends the federal government at all later on.

3. I actually don’t think that state and local government reflect their local constituents better. The fact of the matter is, people don’t really care much about local governments except when they’re screwing something up. I guarantee if you stopped 30 random people on the street in a normal sized suburb, they wouldn’t be able to name their mayor, City Councilmen for their district, or their State Representative. I’ll bet they CAN name the mayor of the nearest big city; the name of their governor, and the name of the President.

4. One of the reasons why people don’t care much about local government is because people move around much more than they used to. For my own part, I have lived in two states, worked in four, and lived in five different cities, and worked in seven different cities. And I doubt I’m that unusual. I have much stronger bonds of affection for my country than I do my city.

5. In many important issues involving civil liberties, it is the federal government that prevents the states from infringing on liberty, not the other way around. The federal government integrated before the states did. The federal government passed anti-lynching laws. The FBI has pretty much removed the grip that a lot of organized crime syndicates had over local governments. Etc. Etc. Etc.

Let me add to these notes that I’m not opposed to local jurisdictions having jurisdiction in some areas but not in others, nor do I think that local communities shouldn’t have any say in how they govern themselves. I just feel obligated to point out that the real world is a lot fuzzier and grayer than Levin implies.

Next Levin talks about one of the benefits of Federalism – the concept that the states can experiments with different policies, and thus inform each other and the federal government about better ways to do things. I agree that that’s a cool feature of the system.

After that, Levin discusses another benefit of federalism – mobility, which I alluded to earlier. The idea here is that “[i]ndividuals with widely divergent beliefs are able to coexist in the same country” because of diversity among states. I think that’s a pretty cool feature, too.

At this point, I’m starting to wonder whether I’m going to agree with Levin about the rest of the chapter! But wait… oh. Never mind.

However, one of the most dramatic events undermining state constitutional authority came with the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment on April 8, 1913. The Seventeenth Amendment changed the method by which Senators were chosen, from being selected by the state legislatures–ensuring that the state governments would have a direct and meaningful voice in the operation of the federal government–to direct popular election by the citizens of each state.

My colleagues Doug and Steven have done the legwork on the ridiculousness of this argument, so I’ll refer you here, here, and here.

I’ll only add one note of my own. Anybody who has ever bothered to read the notes on the debates over the Constitution knows that this idea that Senators being selected by State Legislatures wasn’t carefully crafted to preserve federalism. It was a last minute compromise. None of the major plans for the Constitution included this provision in it. Madison’s Virginia Plan called for Senators to be selected by the House! Hamilton’s plan called for Senators to serve for life, but they were to be selected by electors who were voted for by the people–not state legislators. The New Jersey Plan called for the Congress to remain as it was under the Articles of Confederation. The Pinckney Plan also had Senators selected by the House. The idea of State Legislatures selecting Senators came late in the game – in July of 1787 – under the “Connecticut Compromise.”

Next Levin goes on to criticize the Wickard v. Filburn decision, which in his words “swept away 150 years of constitutional jurisprudence.”

Nonsense.

Although much maligned in conservative/libertarian circles (in fact, I recall arguing against Wickard in my Constitutional law class!) the plain fact of the matter is that Wickard wasn’t a unanimous opinion for nothing. It was firmly in the bounds of the plain text of Constitution. The plain text of the Constitution grants the Congress the power to “regulate Commerce … among the several States” and the plain text of the Constitution grants the Congress the power to “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers.”

In the case of Wickard, it was within Congress’s authority to regulate commerce by controlling the price of wheat. Congress determined that in order to so regulate the price, the amount of wheat grown had to be regulated. Thus, its prohibition against growing excess wheat for private use was perfectly Constitutional. (Whether it was a good policy is an altogether different question — it wasn’t. But that’s not the point here.)

Did this line of reasoning overturn “150 years” of jurisprudence? Hardly. Wickard relies on John Marshall’s 1824 decision in Gibbons v. Ogden, in which John Marshall describes the Commerce Power thusly:

If, as has always been understood, the sovereignty of Congress, though limited to specified objects, is plenary as to those objects, the power over commerce with foreign nations, and among the several States, is vested in Congress as absolutely as it would be in a single government, having in its Constitution the same restrictions on the exercise of the power as are found in the Constitution of the United States.

Moreover, there is an even stronger basis for this line of reasoning in McCulloch v. Maryland, where Marshall noted:

Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the constitution, are constitutional.

This formulation is virtually identical to Alexander Hamilton’s defense of the Constitutionality of the Bank of the United States way back in 1791, where Hamilton wrote:

If the end be clearly comprehended within any of the specified powers, and if the measure have an obvious relation to that end, and is not forbidden by any particular provision of the Constitution, it may safely be deemed to come within the compass of the national authority.

Thus there is a clear throughline of jurisprudence, starting with Alexander Hamilton’s defense of the Constitutionality of the Bank of the United States, through the earliest decisions involving the Commerce Clause, right on down through Wickard.

After this, Levin then complains that the states have become “administrative appendages” of the federal government, and further complains that the “Statists” have constructed a “Fourth Branch of government” vis a vis adminstrative agencies. Both of these arguments have little merit. The Constitution is quite clear that the federal government has supreme authority within its powers. It has every right to ensure that the states abide by federal law. As to the Administrative State, while there’s no doubt that it’s become a large part of the federal government, a bureaucracy to manage the duties of the executive office was not only contemplated in the Constitution, but also part of the very first government. George Washington himself helped create the first executive offices from which the modern bureaucracy emanates.

Levin then spends a paragraph complaining about federal regulations, but its unclear as to what his solution is. The modern economy is large and complex. Regulating that economy requires complexity. I have no issues with streamlining federal regulations and have no doubt that some pruning could be done. That said, some regulations are necessary for a number of reasons, and to simply dismiss them all without addressing the problems for which the regulations are purported to solve is absurd.

Levin then goes on to make a decent point about federalism — namely, that it was to their credit that the northern states resisted federal authority vis a vis the Fugitive Slave Laws before the Civil War. I think that’s a good point and, as I mentioned above, I think there’s definitely some value to a certain degree of give and take between federal and state governments.

But in my mind, this give and take doesn’t have any moral merit. It’s purely one of utility. Whether the federal government or state or local government should be the leading authority in certain areas should be a matter of what works best — not some arbitrary distinctions. Frankly, it makes a lot more sense to me for the Federal government to be the dominant economic regulation. And I wish it did more. For example, it’s silly that, if you get a license to be say, an electrician in Oregon that you have to be re-licensed if you move to Pennsylvania. That kind of local economic regulation serves no useful function. Better that rules governing electricians be centralized. On the other hand, it doesn’t make much sense to me to have the federal government control natural parks — that seems to me to be something that makes more sense for the states to manage. Now, maybe I’m wrong on these two specific policy issues. But the point is that it doesn’t make sense to ascribe some sort of magical power to federalism. We should focus on what works instead.

Levin then goes on to what I think is an excellent point — it was precisely the adoption of the Constitution that did lead to the eventual end of slavery, that did lead to civil rights, etc etc etc.

I have to say that, overall, I found this chapter to be the most interesting of the book so far, and certainly the one with the most insightful points. It is also, and this is no coincidence, the chapter that so far has had the least references to the Statist boogeyman and its associated logical fallacies.

Levin closes with a quote from Madison, and so I’ll do the same:

“A popular Government without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy, or perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance: And a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.”

Next up is Chapter Six, entitled “On the Free Market”, which is over 30 pages long. I wager I’ll be doing this chapter in several parts. Until next time!

Alex,

Thanks so much for reading through this. I can’t bring myself to do it, but it is nice to get the analysis.

One comment, though. You mention that there’s no reason why a PA licensed electrician should be required to be relicensed in OR, but that the national parks should be state managed. Ironically, while I find myself agreeing with your views on this book in general, I think this has it exactly backwards. Local regulations for building/construction etc. make a ton of sense. Think earthquake standards in California vs. tornado standards in Kansas. It makes sense for a tradesperson to have GENERAL knowledge of both, but for the locality to require proof of SPECIFIC and ADEQUATE knowledge of the relevant one. Having a federal authority manage this seems eminently impractical.

On the other hand, national parks are a particular kind of natural resource. The decision to protect vs. mine/log/etc. seems to be a particularly national question. Local control of natural resources CAN be good, but it can also be very damaging, with both forseen and unseen consequences. Think of reversing the Chicago River. Doing so in the 19th century was important for CHICAGO’s development, but has had national and regional repercussions ever since. Frankly, some good and some bad. That damage is often/usually not limited to the state in which the action is taken. This seems precisely the sort of situation the federal government should tackle.

The concept of states as strong, autonomous entities is in many ways a relic of the early Republic. We can see that in the very word “state,” which in most contexts today is virtually a synonym for “country.” And indeed, that’s not far from the meaning it originally had in the U.S.: Jefferson described Virginia as “my country.” It is also notable that the term “United States” was originally a plural. For example, the Declaration of Independence is subtitled “The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America.” The states got weaker over time, and this process was well underway long before the twentieth century; the Civil War had a lot to do with it.

Conservatives who celebrate “federalism” (using the word, interestingly enough, in nearly the opposite sense from how it was used in the early days of our Republic) are typically attempting to make it sound like the federal government stands in the way of the freedom granted by the states. In fact, what’s striking is how often throughout our history the rallying cry of “states’ rights” meant essentially letting states clamp down on individual liberty. The states can be a bulwark against federal tyranny (as in Jefferson’s response to the Alien and Sedition Acts), but the exact opposite may just as easily be the case. The point is that there’s no natural tendency for states to protect freedom any better than the federal government does. In many ways, the opposite has often been the case. But because of the fact that the federal government is the larger and more powerful entity, appeals to federalism have an important emotional component.

I have one quibble. You wrote:

>The federal government integrated before the states did.

The federal government made desegregation universal but wasn’t the first to pursue it.

Kylopod –

It did and it didn’t. The Federal government integrated after the Civil War, but Woodrow Wilson reversed that policy and instituted segregation in the Federal Government. Truman partially reversed this. But you’re right that in the 20th century, some states beat the Feds to the punch.

I think you are wholly wrong on the commerce clause and the Wickard case.

The Commerce power , if taken in context of when it was written and the definition of ‘commerce’ from when it was written , would include the power to control prices nor dictate the ability to manufacture a product.

Commerce, at the time of writing, dealt with trade between the states. Trade of goods, not the manufacture, nor the cost.

Levin is correct, the Wickard case was an abomination of the worst sort. You have fallen prey to the common mistake of interpreting the words of the Constitution using modern definitions. You must use the vernacular understanding from the time of its creation.

So far, your blog of Mark’s book is like a solution looking for a problem.

/slapwrist.

Must learn to proof read on tiny laptop screen.

should read: ……..would NOT include the power to control prices nor dictate the ability to manufacture a product.

Drew,

John Marshall et al rejected this definition of commerce in the 1824 Gibbons v. Ogden case, noted above.

Beat me to it, Alex.

Other things being equal (which they seldom are), I have ever beleived in subsidiarity, which has great practical value in solving problems as close to their origins as possible. As time progresses, we find that many problems and their solutions are being moved up from City or County to State and then to Federal concerns, with a significant delay in reaching a solution, which almost by definition becomes a compromise that satisfies no one.. Education seems to suffer mightily from this malady, for instance.

(As a passing fact, did you know that according to LSU files the number of existing government agencies, boards, committees, authorities, and what not exceeds 1100, and is slated to grow by hundreds? Now that is real complexity in action! Should we not review very carefully each of these entities for possible savings?)

It is apparent that some problems involve adjacent or higher entities and hence it is necessary to move the problem up to the level of authority needed, but hopefully the 10th Amendment still carries its weight, and much is left for the States or the People to do!

“It is apparent that some problems involve adjacent or higher entities and hence it is necessary to move the problem up to the level of authority needed, but hopefully the 10th Amendment still carries its weight, and much is left for the States or the People to do!”

One of the things that always intrigued me is the conservative preoccupation (obsession?) with federal power, when, as a matter of brute fact, your state, city, or town exercises far more power over our everyday lives than the feds do or could. Your state marries you and buries you, and in the interval, the vast, vast bulk of government crapola that comes your way does so courtesy of your state and local governments.

@sam

Indeed, I believe the Founders had the same obsession, while hoping to find the right balance between the two. It isn’t the States that are giving us Obamacare. It isn’t the States that ran up bills for three wars in the ME, and it isn’t the states that have wished abortion on us, or a social security system that has no financial backing in real terms, or have somehow run up the deficit to over 14 trillion dollars. These, and a host of other Federal miscues are at the heart of conserv ative complaints, and they far, far outweigh your little State complaints.

I see most of your complaints as being subsidiarity in action., sam. learn to love it!

It isn’t the States that are giving us Obamacare

Except its the states that will run the exchanges. And the states which already have control over the insurance industry and are being given more power to regulate things.

It isn’t the States that ran up bills for three wars in the ME

Well we can blame one state for some of that. Its in the southeast, and its shaped like a piece of human anatomy.

and it isn’t the states that have wished abortion on us,

The federal government forced you to get an abortion? You poor thing. When did this happen?

or a social security system that has no financial backing in real terms

Well except for its trust fund and the fact that its has never missed a payment.

or have somehow run up the deficit to over 14 trillion dollars.

Except that the States themselves have been swimming in red ink for years. It was fun to see the conservative darling Texas admit this week that their budget crisis is among the worst in the nation, and how they had basically lied to hide that fact last year, all the while plugging their supposedly smaller shortfall with 95% stimulus money.

Marshall::

It is not intended to say that [the discussion thus far] comprehend[s such] commerce, which is completely internal, which is carried on between man and man in a State, or between different parts of the same State, and which does not extend to or affect other States….

Comprehensive as the word “among” is, it may very properly be restricted to that commerce which concerns more states than one. The phrase is not one which would probably have been selected to indicate the completely interior traffic of a state, because it is not an apt phrase for that purpose; and the enumeration of the particular classes of commerce to which the power was to be extended, would not have been made, had the intention been to extend the power to every description

—–

Marshall disagrees with your assertion. You may regulate the ‘navigation’ between the states. We’re still not in the manufacture and production area….INTRAstate activities are beyond and out of reach of the commerce clause. At least as far as Marshall is concerned. No?

@Shocked

I will bother to respond to one of your comments: The only thing in the SS trust fund is a bunch of IOUs from the US Treasury, and to top it off, the outgo from SS exceeds the inflow now. Your trust fund has no cash. If you really believe in the US government’s IOUs, how do you reconcile that with the massive indebtedness we have managed to accrue, that amounts to some $114,000 per household or something close to that. Very soon, we won’t be able to service the debt, so servicing SS is becoming rather duboius.real soon now.

On abortion, just contemplate the following for a moment: incredibly, there have been over 60 million abortions since the passage of RvW. 60 million killings authorized by the US government

That is something to be very proud of, isn’t it? Isn ‘t it?.

“These, and a host of other Federal miscues are at the heart of conserv ative complaints, and they far, far outweigh your little State complaints.”

It’s also the federal government which led the way in eliminating institutional racism in America, overcoming the vicious opposition of several states. But, of course, conservatives opposed the federal government then and just want to forget it ever happened now.

Mike

Drew,

The key phrase you quoted is:

I highlighted the key phrase here. The argument that the Courts have adopted is that there is very little economic activity post the industrial evolution that doesn’t “extend to or affect” other states. In 1824, there was a lot more commerce you can say was purely internal. But nowadays? With commonplace travel and fungible goods imported from all over the country and around the world? Not so much. Scalia noted this fact in his opinion on Raich v. Gonzales.

There are oxes to be gored on both sides of the Federal vs State government issue. What I am against is governmental overreach at any and all levels. In our republic, it is the easy thing for legislators to vote to give away money under some guise or another, and thereby purchase goodwill from the citizens, which it is hoped translates into votes for the incumbent at election time. There are issues that are clearly national in impact that should be decided at the national level, but there are also issues that could just as well be decided by a State or a local authority.

Take the issue of marriage, as sam brought up. Would you rather run down to your local church for the ceremony, or would you rather have to travel to, say, Washington, D.C..to have the knot tied by a proper Federal official (assuming, of course no proper federal official such as a Federal Judge is colocated with you.)? Then pose the issue of war. War is decided at the Federal level. The final nail in the slavery situation throughout the US was decided by an Amendment to the Constitution, specifically Amendment XIII, which required the President, most of Congress, and the legislatures of most of the States to ratify.it.

@ Manning:

“The only thing in the SS trust fund is a bunch of IOUs from the US Treasury, and to top it off, the outgo from SS exceeds the inflow now. Your trust fund has no cash. If you really believe in the US government’s IOUs, how do you reconcile that with the massive indebtedness we have managed to accrue, that amounts to some $114,000 per household or something close to that. Very soon, we won’t be able to service the debt, so servicing SS is becoming rather duboius.real soon now.”

No, no, no. This is so very, deeply wrong. I suggest you learn how money works, and what Federal spending is. Cash has nothing, zlitch, nada, niente to do with it. The Federal government is not operationally constrained in spending. It has a limitless ability to meet its debt obligations, because it does not tax or borrow to raise revenue. This misconception arises out of early 20th century economics, to the extent it was even true then. We have fiat money now. Look it up.

Well, if I am wrong, I am wrong, but I would say that:

a) the government should be operationally constrained in spending if it really isn’t;

b) what is it that I have to pay to the government’s Internal Revenue Service every April if not taxes, which from the government point of view is revenue?; and,

c) what is it that China banks hold from us valued at well over over a trillion dollars if not borrowings?; and,

d) what is it that the treasury does every so often if not sell what amounts to government dollar IOUs (loans as bonds) with interest to the world? and,

e) what is all this talk about a 14 trillion dollar national debt and its servicing needs?

But, then, I am quite obviously not up on modern Alice in Wonderland financial shenannigins that appear to allow us to keep on keeping on world without end!

@ Alex

One comment: you continue to point out that various individuals at the Constitutional Convention had vastly differing opinions as to what should be in the Constitution on a variety of issues. In my opinion, such individual opinions are totally and completely superceded by their signing of the eventual Constitution itself, compromise that it is. Hence their previous opinions are not worth squat. Nor are opinions of individuals that were not in the convention and didn’t sign the Constitution worth a mention.

Then too, the States are sovereign, regardless of how they got that way, or whose opinion it ws that they shouldn’t become sovereign before the fact.