Federalism and Democracy

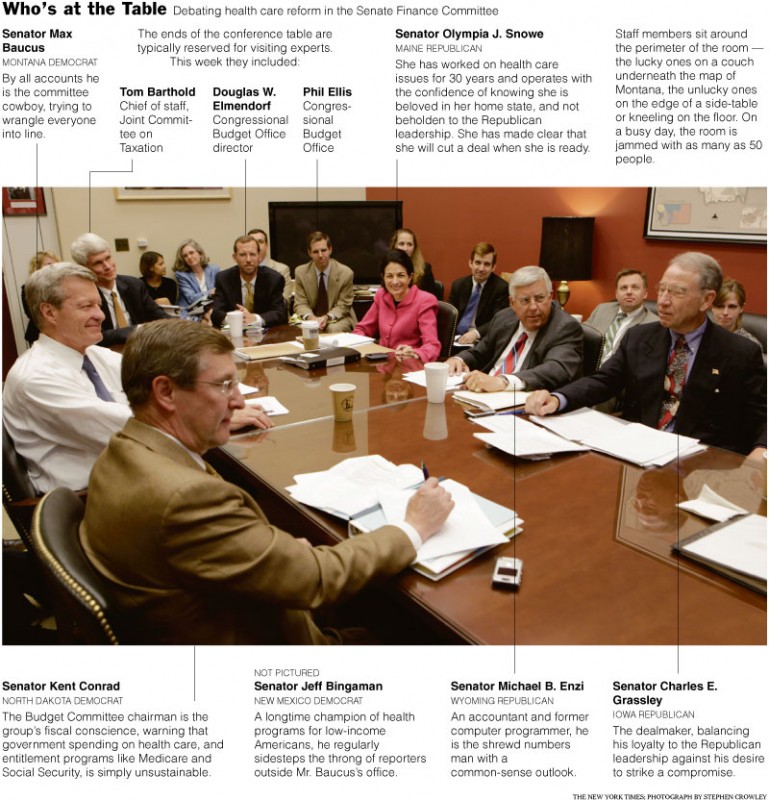

Continuing a long-running theme at his blog, Matt Yglesias laments that Senators from small states wield so much power. The latest fuel is a NYT feature on six moderates who are supposedly the linchpins to putting together a bipartisan health care deal and who routinely hash out the details of same over snacks.

Continuing a long-running theme at his blog, Matt Yglesias laments that Senators from small states wield so much power. The latest fuel is a NYT feature on six moderates who are supposedly the linchpins to putting together a bipartisan health care deal and who routinely hash out the details of same over snacks.

[V]ast power is being wielded by people who, in a democratic system of government, would have almost no power. We’re talking, after all, about Max Baucus of Montana, Kent Conrad of North Dakota, Jeff Bingaman of New Mexico, Susan Collins of Maine, Mike Enzi of Wyoming, and Chuck Grassley of Iowa. Collectively those six states contain about 2.74 percent of the population, less than New Jersey, or about one fifth the population of California.

There’s no doubt that the small states have disproportionate power in a system wherein all states get equal voting power. Then again, that was the whole point (see: Compromise, Great).

Would we design the system this way if we were starting from scratch? Probably not. But it made good sense at a time when the several states were sovereign entities banded together for national defense and international commerce.

Does this make our system undemocratic? Not any moreso than, say, the fact that five unelected people on the Supreme Court (about 0.00 percent of the population!) can overrule an act of the legislature. Or that it requires a supermajority to amend the Constitution or ratify a treaty.

Matt is also frustrated that the above-mentioned six come from predominately rural states and therefore ignore the interests of urbanites. But that’s just a function of self-selection in a particular instance. It’s certainly conceivable that a group of Senators from larger states who happen to be on the fence on some other issue could dine together regularly and use their informal gatherings to work out their policy positions.

The problem people have is that now Senators are democratically elected, rather than being appointed by the state legislatures.

Under the original design it made more sense, because the Senators represented state governments, not individual citizens, and thus every state government had equal representation. Now that they are directly elected by the citizens of the state, not all citizens have the same representation.

I love how you can talk about the Great Compromise and “international commerce” without mentioning the basis for the agreement: how to deal with the slavery issue.

The Connecticut compromise paved the way for the Three-Fifths Compromise. These elements were explicitly designed to maintain slavery in the US.

Lets not dance around this with an Obama-style “we might do it differently if starting from scratch, but since we’re not, oh well…”

The constitution was explicitly constructed to maintain antidemocratic stratification. Until we make more serious reforms, this legacy is still institutionalized.

THere have been amendments over the years which have done precisely this–but that shouldn’t mean that conversations pertaining to democratic reform should stop.

I don’t think the Great/CT and 3/5 compromises had much to do with one another. Indeed, the 3/5 Compromise wasn’t so much about slavery — which was separately institutionalized in the Constitution — but rather about the distribution of power and costs.

I don’t think that “democracy” precludes federalism. And super-governments comprised of formerly sovereign or still-sovereign entities (see, the UN, the EU, NATO, etc) will naturally have skewed power distributions.

I’d have to check, but I thought one of the reasons California was so large was that it became difficult in the antebellum era to admit states without Congressmen being caned in chambers.

In any event, the perverse outcome is that California would have more representation(*) if it is was divided into more states and potentially more accountable state government as well. Matt likes to go the other way to get less representation and less democracy for some some states.

(*) This assumes that there are primarily persistent common interests among the multiple California “states,” but this may not always be true.

I am not sure if the historical record supports this view. The equal representation in the Senate was agreed upon on Saturday, July 7, 1787.

The next order of business they moved to was representation in the House and the Three Fifths compromise was agreed to 5 days later.

It is disingenuous to separate power and costs in the constitution with the slavery question. Don’t take my word for it, rather look at what founding father Rufus King said years later:

Essentially, King makes the same argument as you do about political expedience at the time. He differs, however, in saying that there is a need to reform these original conditions.

The 13th Amendment did away with the 3/5 Compromise, no?

And how often has Young Mr. Yglesias ahistorically complained about the obscene levels of power power wielded by the small state northeastern cabal of Senators Kennedy, Kerry, Dodd, Sanders, Leahy, Shaheen, Reed, Whitehouse, and Lieberman?

Is 535 people allegedly representing 300 million a democratic system? I think it strains credulity.

A different question entirely. I’m not sure where one draws the line. It may simply not be manageable to truly represent 300 million people. Even at 1 rep per 100,000 you’d need 3000 reps. They can hardly get anything done with the 535 they have!

All the wailing about how poorly we govern ourselves misses several salient points:

1. We’re not a democracy. We’re a democratic Republic (“The Republic for which it stands …”).

2. For all of its problems, our system of government works better than anything else in recorded history. We are the greatest country in the history of the world (and f**k all you America haters).

3. Government cannot solve everyone’s problems — and it ought not to try (stick to provide for the common defense, promote the GENERAL welfare, etc.)

4. Like the electoral college, giving all states the same powers in the Senate works pretty well. If we governed ourselves by simple majority the bigger population centers (and their gimme, gimme mentalities) would hold sway all of the time. As for the electoral college, if we had a simple popular election for President, no one would campaign in the smaller states and their voices wouldn’t matter.

5. Eventually, we get things right. GWB spent his political capital doing what he thought was right (and, for the most part, was right) and he became so unpopular that the commies were swept into office. So be it. Obama and the rest of the rabid lefties in Congress are teaching us all a sharp lesson. This will correct itself in a couple of years (less than that, probably). Is this a great country, or what?

You’re saying this as though it’s a bad thing.

One representative would be ever so much more efficient than 535. Is efficiency relevant? I think that adequate representation is a higher value.

They essentially do that in France, where the president is inordinately powerful, and we still call it a “democracy.” At some point, inefficiency creates a lack of representation, too. I’m not sure where that line is.

“The number ought at most to be kept within a certain limit, in order to avoid the confusion and intemperance of a multitide”

— James Madison, Federalist #55

From the same number:

the implication being that there is such a thing as being unrepresentative.

BTW, the authorship of that number is disputed. Sounds more like Hamilton to me.

Jefferson thought one representative for every 30,000 was about right; Washington thought it was too many.

We have communications technology today that the Founding Fathers never dreamt of. Surely that could be exploited to eliminate the problem suggested by Federalist 55. For example, there’s no real need for Congressmen to meet physically. For most purposes teleconferencing would be fine.

Indeed, all the rest of that paper and the following one were focused on just that criticism. Of course, the house had 65 members at that point.

Really? It didn’t have Hamilton’s cockiness that I find in so many others.

Travel concerns weren’t really a part of that paper, it was more about representation, corruption, and the connection the representative would have to his electors.