Forecasting 2024 Way Too Early

There are at most eight toss-up states for the 2024 Presidential election.

David Lauter, LAT (“Analysis: The road to the White House now runs through Georgia and Arizona“):

When President Biden won Georgia and Arizona en route to the White House in 2020, many Republicans called the outcome a fluke, a one-time response shaped by a deadly pandemic.

Tuesday’s Senate runoff in Georgia, together with the November election results in Arizona, proved that argument wrong. The two states, both solidly Republican only a few years ago, now have four senators elected as Democrats to full six-year terms. (Arizona Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, a Democrat when she won election in 2018, announced Friday that she’s changing her affiliation to independent, which could protect her against a primary challenge if she runs for reelection in 2024. The state won’t have a Republican in either Senate seat or the governorship for the first time since 1950.)

The midterm outcome makes clear that the nation’s political battleground has shifted: The road to the White House in 2024 will run through the South and Southwest. The big industrial states bordering the Great Lakes, which dominated the last several election cycles, remain important, but no longer as exclusively.

That will change not only where presidential candidates campaign, but also the nature of the voters on whom they focus: For Democrats, the shift will intensify the need to mobilize the Black and Latino voters whose support — and large turnout — they need in order to win southern and southwestern states. For Republicans, the fact that both states have relatively young electorates could draw greater attention to the party’s growing deficit with millennial and Gen Z voters.

Oddly, Lauter’s own analysis undercuts this thesis but reinforces a more important point.

A generation ago, a majority of states were at play in presidential campaigns. No longer. The list of truly competitive states has steadily shrunk. Even as Georgia and Arizona have joined the list, other states have dropped off.

Florida, which was among the most closely divided states from 2000 to 2016, shifted heavily toward the GOP in 2020 and moved even further in this year’s midterms, in part because of the gains among Latino voters that Republicans have made in the state. Given the high cost of campaigning there, Democrats aren’t likely to sink significant time and money into trying to capture the state in 2024, especially if Gov. Ron DeSantis is the GOP nominee.

Similarly, Ohio, which was the quintessential election battleground for decades, appears to have moved out of reach for Democrats — with the possible exception of incumbent Sen. Sherrod Brown — as the white, working-class voters who predominate in the state shifted to the right in the Trump era.

On the other side of the ledger, states with large shares of college-educated voters have become increasingly difficult for the GOP. This year’s midterms were especially troublesome for Republicans in two states that fit into that category. In Colorado, Republican Joe O’Dea’s inability to come close to Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet, who won reelection with 56% of the vote, indicates that the once-purple state can be considered solidly blue. And the GOP’s failure to make significant gains in Virginia suggests that the 2019 victory of Gov. Glenn Youngkin may have limited predictive value.

Overall, both parties begin the presidential contest with about 220 electoral votes they can pretty well count on — 50 short of the 270 needed to win. Arizona’s 11 electoral votes and Georgia’s 16 would cover more than half that gap.

Partisans may object to writing off some states as noncompetitive — Democrats continue to dream about making Texas a purple state, for example, and Republicans talk about Minnesota and Oregon. The midterm results, however, don’t show much evidence for those states being close to flipping.

Democrats’ hopes for Texas receded when they lost ground with Latino voters in the state in 2020. While that situation didn’t worsen in 2022, it didn’t get better.

As for GOP stretch goals: In Minnesota, Republicans lost their majority in the state Senate, giving Democrats full control of state government. And in Oregon, Democrat Tina Kotek won a three-way race for governor in which Republicans had invested a lot of hope.

Only eight states start the 2024 election cycle truly in doubt — Nevada and Arizona in the Southwest; Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania among the big industrial states; North Carolina and Georgia in the Southeast; and New Hampshire.

The midterm elections make that a problematic list for Republicans because, as longtime Democratic strategist Simon Rosenberg notes, Democrats made gains in each of the battleground states, even as they suffered setbacks in less competitive states like New York and California.

Emphases mine.

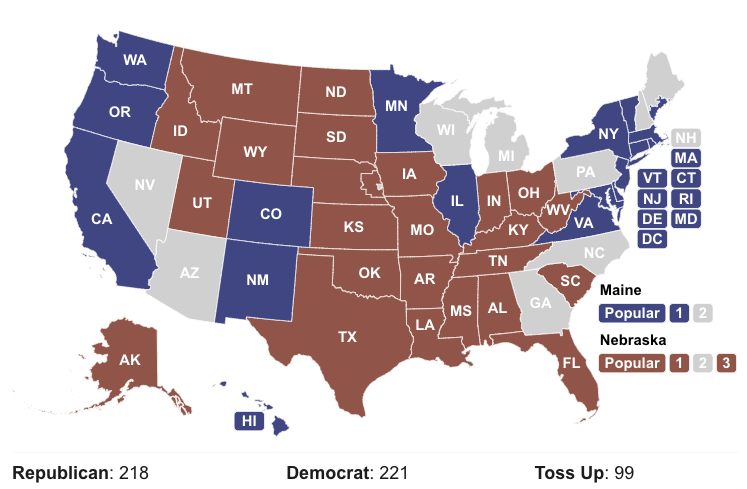

Taegan Goddard, who pointed me to the piece, provides an interactive 2024 map that starts off like this:

And, honestly, I think this overstates the competitiveness of the races.

- Arizona has voted Democratic just twice since 1952—1996 and 2020. And most of the Republican wins have been by comfortable margins. And, even with Trump dragging down the ticket in 2020, it came down to 0.3%.

- Georgia voted against Trump in 2020 but otherwise has voted Democratic only three times, twice for native son Jimmy Carter (1976 and 1980) and once for Southerner Bill Clinton (1992), since 1960.

- North Carolina has gone Democratic only twice—1976 and 2008—since 1964. Yes, the last four have been relatively close. But it’s hardly a toss-up state.

- Minnesota is a blue state. Period. It last went Republican in 1972 and has otherwise voted reliably Democratic going back to FDR’s first election in 1932, with the exception of Dwight Eisenhower’s runs in 1952 and 1956.

- Wisconsin voted for Trump by the narrowest of margins in 2016. Otherwise, though, it hasn’t voted Republican since going for Reagan in 1980 and 1984.

- Ditto Pennsylvania. Aside from going for Trump in 2016, it’s gone Democratic in every single other contest since 1992.

- New Hampshire came this close to voting for Trump in 2016 but didn’t. Indeed, the only time they voted Republican since 1992 was for Bush the Younger in 2000.

- Nevada is closer to a true toss-up, with most of its Presidential votes since 1992 pretty close. But it has voted Democrat four straight elections and six of the last eight (the George W. Bush elections of 2000 and 2004 being the outliers).

Just musing here (because I’m too lazy to google) but I wonder how the transitions look in states that have shifted allegiance? I wouldn’t be surprised if once it breaks against tradition it either hastily retreats or makes the transition in one or two more elections.

Ok I broke down. Here’s a link to state’s voting histories. The first ten or so seem to prove out the “quick transition” theory.

And why the heck do we consider Florida a swing state? In the last 18 presidential elections it’s only gone Dem 5 times and two of those were Obama and once was Kennedy, both of whom seem to be outliers of some sort.

@MarkedMan: Your facts are jumbled. Florida went for Nixon, not Kennedy, in 1960. It went for Carter in 1976, but then for Reagan in 1980.

You mean 2020.

It went to Bill Clinton in 1992.

@MarkedMan: @SC_Birdflyte: I think a broader point is that it’s flawed thinking to try to determine a state’s “swing-state” status by looking decades into the past. Why should how a state voted in the ’70s or ’80s be relevant to today? States shift in their partisan tendencies over time. Before the 1990s, New England outside of MA and RI was strongly Republican. Missouri was one of the prime bellwether states of the 20th century; now it’s solidly red. Virginia used to be the most reliably Republican state in the former Confederacy; now it’s completely flipped. The fact that Arizona was reliably Republican for decades proves absolutely zip about its future.

@Kylopod: Fixed. Not sure what happened there—I linked to the correct outcomes.